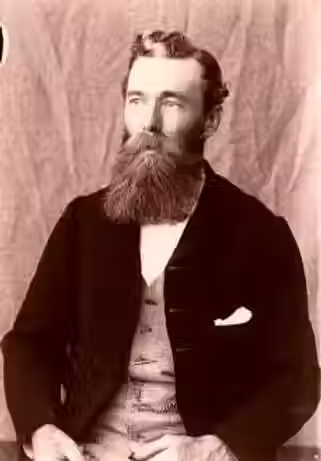

Harry Tilbrook in New Zealand

Henry Hammond Tilbrook became the founding editor of the Northern Argus in 1869, the newspaper of the Clare Valley, which was published until 2020.

-

When Tilbrook was about six years old, in 1854 the family sailed to South Australia on the Albermarle.

-

He worked for a short time as a typesetter at the Register in Adelaide (1861-3)

-

as well as working as a lamb minder for a short time, for Sir Thomas Elder (1864).

-

Tramped all over the same area (1865). Grocery delivery in Glenelg.

-

-

Worked at Ooraparinna Cattle and Sheep Run, far north of Wilpena (1865).

-

Enticed by the gold rush at the time, Tilbrook moved to New Zealand in February 1866 to try to make a living prospecting.

-

After having no luck with gold (in the rain), he moved on to work (1866-1868) for the Grey River Argus in Greymouth (first published 1865).

When the ‘tide in the affairs of man, taken at the flood, leads on to fortune’ arrived, I was just ready to take advantage of it. (William Shakespeare's play Julius Caesar, specifically Act IV, Scene 3)

And I did seize the opportunity and rode on to fortune and happiness, the latter lasting for thirty-seven and a half years.

The ‘tide’ in my own affairs which led me on to fortune occurred in far-away New Zealand.

The old horse-pistols were formidable affairs. I had one. But later I obtained the six-chambered revolver which I afterwards took with me to far-away New Zealand, where it was stolen from my tent by bushrangers.

Around the camp fires at night, we theorised as to the origin of alluvial goldfields. Camping on a plain with low, rocky, sheoak-topped ranges on either side, we demonstrated to each other how gold, in the course of ages, was washed out of the hills on to the flats and creekbeds, and concentrated in gutters and pockets.

Then how these leaders and pockets would, in the course of further ages, be buried deep beneath the surface by other detritus.

I myself was quick to take the gold fever. What newspapers we had seen told us of discoveries of the auriferous metal in the southern portions of New Zealand, and I was already making up my mind to go there and try my luck.

Blank – a Lancashire man – and I both got the gold fever, and decided to go to New Zealand together to try our luck there. He also had a brother, living in the Province of Nelson, and near the city of that name. So he would have somewhere to go in the event of failure on the goldfields.

Mr Sims endeavoured to get me to stay with him, wishing me to go back to Ooraparinna to assist him in the management. But my mind was made up. He generously paid me off at the rate of One Pound sterling per week from the time of my engagement, although our agreement was for fifteen shillings a week only.

I was seventeen and a half years of age then, and I had been in his service just twelve months.

To anticipate a little, my salary in New Zealand within two or three months of this time was Three Pounds Ten Shillings per per week, with almost immediate rise to Four Pounds Ten Shilling per week, and afterwards to Six Pounds sterling per week.

The salary paid to Mr Chas. Dawson, as manager of Ooraparinna, was Three Pounds per week and rations for himself and family.

In Adelaide at that time, the wages paid to laborers was six shillings per day. The hours were from six a.m. to six p.m., with an hour for lunch.

December 20th, 1865.

We arose early, walked five miles to Kooringa, and caught the six a.m. mailcoach for Kapunda.

Having travelled the fifty miles to Kapunda, we stepped into the afternoon train for Adelaide. I found the carriages so stuffy that I felt almost suffocated. This was the effect of being in the open air day and night for so long a time.

Fifty miles landed us in Adelaide by night. As it was late, we camped for the night in a plantation on Le Fevre Terrace, North Adelaide.

Next morning I presented myself, swag and all, to my darling Marianne – the beautiful girl whom I have now lost for ever. Her lovely arms were thrown around my neck, and at last we two were supremely happy.

I unfolded my plans to her of trying my fortunes on the New Zealand goldfields. At first she cried quietly. But she was so optimistic, and had such faith in me, that she soon acquiesced in the arrangement, and even looked forward eagerly, but sadly, to my departure.

Youth is ever bright and hopeful. She never doubted my ability to get on, on this or on other occasions, or my love and loyalty to her own beautiful, quiet, calm self. She was growing a most beautiful and handsome young woman, fine-limbed and well developed.

And she was being brought up in refinement as a lady. She played the pianoforte and sang well. She had many music pupils of her own; whilst her mother, who had been brought up under masters, taught French, taught music to advanced pupils, and other educational things.

We had a fortnight of bliss together. Every evening Marianne played the piano to me, and duets with her mother, and sang songs to me that I loved. She was being trained in a school choir by Mr Fred. Unwin, she having a nice, rich, voice. Mr Unwin was organist of Walkerville church of England.

Then came the inevitable parting! How I hated them! She did not come to the railway station or ship to see me off, but said good-bye in the house. Her heart seemed broken. She sobbed and clung to me, and it was only with an effort that I tore myself from her clinging embrace. She was one of few words, but deep, steadfast, feeling.

A TRIP TO MELBOURNE BY SEA. 1866

In the S.S. ‘Aldinga’ – a fast Boat. January 3rd, 1866 –

On this day we started from Port Adelaide in the S.S. Aldinga, bound for Melbourne, Victoria. The only person to see me off was my brother George. He met me at the Adelaide Railway Station and said good-bye there.

He showed great concern that no one should go and bid me bon voyage. But I had been used to ‘going on my own’ since boyhood, and expected no other treatment. Nevertheless it was a pleasant surprise to me to find one solitary individual who took that much interest in me.

In this instance I had a mate with me. But what kind of a help he was will be seen later on, for when difficulties arose, he quietly deserted me.

My brother George was such a ‘swell’, too! He used to attend dances and parties at the Duttons, the Sparks’s, the Wyly’s, the McDermott’s (the S.M.), and invariably wore a dress suit.

Bill Wyly – who, by the way, was a great ‘swell’ also – told me years after George’s decease that the most treasured possession he had was a Testament presented to him by my brother George.

Harry H. Dutton and I chummed together in the Christ Church choir under Mr Greenwood, the organist. Harry and his mother lived in a two-story house next to Bishop Short’s.

They were poor then, but became rich upon the decease of his uncle. Then Harry took up the ownership of Anlaby sheep station, near Kapunda.

When I knew Harry, he was a clerk in a Bank. Harry’s family continues there, but Harry himself is no more.

But to continue. My next meeting with my brother George was thousands of miles away.

The S.S. Aldinga was at this time the most rapid boat in Australian waters. She could do the journey of six hundred miles to Melbourne in forty-eight hours. After leaving Port Adelaide the weather was stormy. The waves were high. The Aldinga did not ride over them, but, diving her nose into them, she worried her way through without slackening speed.

I stood it until Backstairs Passage, between Kangaroo Island and the main land, was reached – the same night. Then I turned up my toes! I was so sick I did not care whether the ship ever came up again after burying herself in the billows. My mate was about as bad as I. The deck was awash all the time.

The night was dark. I was sitting on the deck, helpless, wet to the skin. All night it lasted. Next day, when three hundred miles on our journey, we passed Cape Northumberland, and saw the Lighthouse there, and, in the distance, the outlines of those extinct volcanoes – Mount Gambier and Mount Schank.

The voyage was rough all the way till Port Phillip Heads were reached on the afternoon of January 5th, 1866.

Here is an apt quotation from that clever poet Walt Whitman:–

‘MAL-DE-MER.

When the ocean takes a notion to indulge in an emotion

As you’re sailing o’er its bosom broad and blue,

Strict devotion to a potion of a lemon-flavoured lotion

Is, dear reader, very plainly up to you.

It’s a failing when you’re sailing and the briny air inhaling

To imagine that the ocean’s always kind.

There’ll be trailing toward the railing of a lot of folk bewailing,

Ere the ship has left the outer reefs behind.

When the ceiling gets to reeling, and a pallid, lonely feeling

(As if every friend you know on earth were dead)

Comes a-stealing and appealing till it gets beyond concealing,

Then you’ll know the thing referred to in our ‘head’

Immediately we entered smooth water inside the Heads I was well again! Going through Port Phillip and Hobson’s Bay as far as Sandridge – now called Port Melbourne – we proceeded up the narrow, low-banked, Yarra River. There was no canal then.

Our boat being so speedy threw out two great waves in her wake as she proceeded up the very narrow waterway. At one angle or bend her bows almost overhung the land as she negotiated the sharp turn.

Further along, a man was sitting on a heap of silt, complacently fishing with rod and line. We gazed at him in wonder! Surely he knew the big wave was coming on his side – the starboard! as well as one on the port side. Why didn’t he clear out? Skedaddle? Vamoose? No! He stayed there like a martyr at the stake. Only, his stay was voluntary.

We passengers awaited the catastrophe with interest. After the steamer had passed him, our starboard wave rose up to him gently, caught him full in front, and landed him on his back on the flat ground beyond, much to our amusement and the angler’s great astonishment. He was as wet as the fish he was catching!

On we went, through the Yarra smells, which at that time could almost be cut with a knife and retailed in chunks, and finally moored at Flinders-street wharf.

I was struck by the fact that, on getting through the Heads, the ship was ‘tidied up’. Her sails were rolled up and covered with clean canvas covers, and everything was put into presentable trim ere she hove to in Melbourne City.

Not so at Port Adelaide! The steamers arrived there en deshabille – in their kitchen clothes! But, then, Adelaide was only the little ‘Farinaceous Village’, according to Melbournites, and of no account.

After the Aldinga’s time, the newer steamers did the journey in thirty-eight hours.

Upon reaching Melbourne, Lodging-House touts stormed the boat.

Under the guidance of one of them, my mate and I took our swags to a Boarding House in King Street, at the top of Bourke street, into which it emerged. We were, in short, on top of the hill on the further end of Bourke street from Parliament Houses.

Bourke street is the great shopping centre of Melbourne. The Post Office is in the valley where Elizabeth street crosses intersects it. Thus our lodging-place was not to be on the ‘cold ground ‘ – at least so we thought; but the tale is not all told yet!

Melbourne streets are hilly. From the top of our hill, Burke street was on a slope down to Elizabeth street, at the P.O. corner; then there was an ascent to Parliament Houses on the further hilltop.

A VOYAGE TO NEW ZEALAND

By H.H.Tilbrook January 1866.

In the meantime, while in Melbourne, we paid Seven Pounds sterling each for a passage in a new iron steamer named The South Australian, 1000 tons burthen. There was only one class, and that was steerage.

She was bound for Hokitika, on the West Coast of the Middle Island. Hokitika was to be her last place of call – I was going to write ‘port’ of call, but there is no port there, and never will be. She was to voyage all around the Middle Island, pass through Cook Strait, and touch at Wellington on the North Island, thus giving us a splendid run for our money.

Foveaux Strait, between the Middle Island and Stewart Island, would be the first strait to pass through.

Touts were out everywhere in the Melbourne streets on the look out for prospective passengers, as many opposition boats were running; and we learned, when on board, that many people paid only Six Pounds for the trip. We inspected the steamer as she lay at the wharf in the Yarra, then booked our passages.

On the day appointed for sailing, we went to the Flinders street wharf to get aboard – but the vessel was gone! Here was a fix! We went back to the shipping office, when it was explained to us that the steamer had partly loaded in the river, and had then gone to Sandridge to fill up.

We hurried there by train, explored the Sandridge Pier, found the boat, and hopped aboard. We had placed all our things in a bunk as she lay in the river, and we naturally thought we had lost all our worldly possessions. Not so, however. We found them intact where we had put them.

I noticed one fine, handsome, woman, young and fair of complexion, sitting on the deck. She was seasick through the slight movements of the ship whilst at the wharf! But on getting out into the rough and rolling ocean she was as well as if upon land.

On January 13th, 1866, we bid adieu to Sandridge Pier, steamed out of Hobson’s Bay, through Port Phillip, and out past The Heads, into the Southern Ocean, thence through Bass Strait into the Tasman Sea, leaving Australia behind.

The S.S. South Australian was the fastest steamer in this trade, being one of the newest. But although the most rapid vessel, she was not very fast. She was an iron boat, the plates being about three-eighths of an inch thick. That was all that stood between us and the waves. There was no lining to the ship.

As soon as we started, it was seen that the vessel had a list to starboard. In order to remember which was ‘port’ and which ‘starboard’, I memorised the two words thus: – ‘Port’ – left hand – four letters in each word. So in my mind p-o-r-t and l-e-f-t were synonymous. On the other hand: – Starboard – right hand. No need to go further. Both longer words.

We had two hundred passengers aboard, amongst them two dozen women. A portion of the cargo hold had been partitioned off, and rough bunks three tiers high fixed there for the passengers. These bunks were so narrow that a man could not lie on his back. And the space above was so low, that it was impossible to sit up. We had to crawl in sideways. This refers to the centre lot only.

The women’s cabin – rough and temporary like our own – opened into ours. As the door between the two was being constantly opened, there was little privacy for them. They could not avoid being seen en deshabille; but they did not seem to mind. Moreover a window from the steward’s apartment opened right into their domicile.

All the ladies were of the right calibre – not a silly, useless, namby-pamby one amongst the lot! The fat girl I have written of was a jolly one. She made friends with all the men, and every one liked her. ‘Flash Harry’, from Ballarat, took her especially under his wing, and went ashore with her at the various ports we came to. Other men also had their turn. She treated them all impartially.

I was too young myself to be other than an amused looker-on. During a fight between two men in the hold, this buxom dame sat on the deck above, looking down the hatchway, and applauded. Clapping her hands, she shouted, in great glee, ‘Go it, boys! Go it boys!’ She bunked alongside a strange man at the foot of the stairway. But as all slept in their clothes, no one took any notice.

It strikes me now that she was of German nationality, although speaking perfect English.

As we left sunny Australia behind us, we got into rough weather. Our first port of call was to be Bluff Harbor, in Foveaux Strait, at the southern end of the Middle Island. Thus we were getting further south every day. The straight distance was one thousand two hundred miles.

Life on board was mixed, for the people themselves were a mixed lot. As in the Bush, some of the biggest scoundrels were there, and some of the best one could wish to meet. I took no chances, and kept my money securely in the pigskin belt. Even my mate did not know I had it. I have the belt yet.

My swag, with all its belongings, was safe in my bunk. Amongst its contents were the six-chambered revolver from Ooraparinna and a bowie – or sheath-knife to wear on a saddlestrap around the hips. Yes, and I still had my silver-plated steel spurs – which were of no use to me, however, in New Zealand.

Leaving Gippland behind us, we steamed and sailed through the Tasman Sea, and kept steadily on for several days and nights. In one portion of the Tasman Sea we sailed through waters that were tinted red. Someone said it was caused by shrimps! And we all accepted the explanation! forgetting that shrimps were not red until boiled.

One night we witnessed a most interesting sight. The ocean was phosphorescent, flashing out ghostly white lights in great abundance. The effect was most beautiful. We hauled up bucketfuls of the sea water, but could not find the animal cules which caused the flashes. I understand, now, that this phosphorescence is caused by pin-head jelly fish.

The men ‘swapped yarns’. One hang-dog-looking Australian, lean and gaunt, told us how he had swindled two settlers on the river Murray. He had cut a lot of cordwood on the river. He sold the wood to a settler in Victoria for cash. Then, crossing to the New South Wales side, he sold the stacks again to another settler. He then cleared off and let his victims settle the matter between them as best they could. The wood was for use on the river boats.

But it was mostly in their dealings with the fair sex that many of these men – especially the younger ones – showed themselves utterly unscrupulous. And yet the girls always thought the men were in love with them! The trusting creatures!

Our boat had all her spanker sails and jib sails spread to the wind night and day. The weather became rougher each day, and the sea, with its huge waves, rougher still. On the 18th of January, 1866, it culminated in a terrific hurricane.- - -

Soon I began to feel that I was getting seasick! I had had a surfeit of that on the sea trip between Adelaide and Melbourne, and had escaped it on this voyage so far. Grabbing an onion that was floating past from the broken deck cargo, I bit and scratched it, and held it to my nostrils. It acted as a tonic.

In a few hours, continuing the process with fresh onions, the qualmishness gradually wore off. Oh, what a relief! For to have been ill as well would have been awful! In health one can endure almost anything. Hundreds of tons of water came over the bulwarks on our side, and in a short space of time all the sheep and other small live stock were drowned.

The crew crept about as best they could, looking after the sails and other matters. Once the mate was being washed overboard just alongside us, when one of the crew grasped him by a leg and pulled him aboard again.

The storm lasted a day and a night. During daylight, all these various events were interesting to us three spectators. But as a set-off to this, we had to go through the pitchy-blackness of the night, with the raging waters around us, and could see nothing. Then those below were better off than we above.

For all that, however, I would not have changed places with them on any account. We had some knowledge of the condition of the ship; they had none. There was nothing but white foam on the surface of the ocean as far as we could see it. Even during daylight the spray and thick atmosphere circumscribed the vision to a few hundred yards around the vessel.

The Captain and officers, to say nothing of the crew, had a very anxious time of it. And what about the engineers and stokers down in the stokehold? Heroes, every man Jack of them! They all did their duty manfully, and not one shirked his work. By the way, I have seen these stokers, naked to the waist, come up on deck in ordinary times to let the cold wind lave their heated bodies.

At daylight the storm was abating, and eventually the proper course was once more taken. The hatches being removed, the passengers rushed on deck to see about things. They saw a scene of desolation around them that told its tale. I could not get into a change of clothes, so walked about till dry. And that night I slept in my bunk.

By this time the ship had a still bigger list to port, the cargo having shifted considerably under such treatment.

New Zealand now came into view. We passed close by the ‘Solander’ – an island named after Dr Solander, the naturalist and botanist of Captain Cook’s first expedition around the world in 1768. This rock was a pretty sight, standing there alone in the ocean.

On the 19th January, 1866, we sighted Stewart Island. The highest land on that island is three thousand two hundred feet above the sea, and is covered to the crests of the mountains with fine timber. It lies in lat. 47o S.

This being the southernmost island of New Zealand, is a cold region. The island is extensive – Six hundred and sixty-five square miles – and is called, or was called, The South Island by the inhabitants of New Zealand, the three being spoken of as ‘The North Island,’ ‘The Middle Island,’ and ‘The South Island’.

Outsiders take no stock of Stewart Island – whose area, it will be noticed, is about equal to that of a moderately-sized Australian sheep run.

Passing through Foveaux Strait, we arrived The Bluff Harbor on the same day. ‘The Bluff’ is in the Province of Southland, and is the port of Invercargill. A railway had just been constructed from The Bluff to Invercargill, a distance of twenty-two miles. It was not in use, however. This was the only railway line then in existence in New Zealand.

Without a doubt, ‘The Bluff’ is one of the most desolate places I have ever struck. It is in a bleak, miserable spot and I, for one, was glad to leave it.

In my diary I have it written, ‘Bluff Harbor, Campbelltown.’ As a matter of fact, Campbelltown is a port inside the Harbor.

We left the same evening. Passed Ruapeke Island, out in the South Pacific Ocean. Going around several headlands, we arrived at Port Chalmers, the port of Dunedin, on January 30th, 1866, having voyaged the whole of the night and part of the day.

Going up the long estuary, or river, the combined landscapes and seascapes were beautiful to look upon. On the left were low ranges, with tiny Maori huts on the slopes. On the right was lowland, with the wide stream winding through it.

By and by we saw some long war canoes, each manned by about a dozen Maoris, all well built and able-bodied. In complexion these Maoris were as fair as Europeans. They managed their canoes with great skill.

They kept rythmetrical time with their broadended paddles, which they dug firmly into the water, driving the canoes along with fair speed. These vessels were really doug-outs from one tree. The men were tall and pliant, with plenty of flesh on their bones without being obese.

Steaming up the stream for some miles, we anchored in Port Chalmers, there being then no wharves for us to get alongside of, at least not suitable for our vessel. To get to land, therefore, we had to hire a boat.

Here our merry damsel was taken ashore by some of her admirers, one of them being, of course, ‘Flash Harry.’

The rest of the time, she was engaged in the pastime of catching barracouta – a slim fish two feet or more in length. These the sailors scaled, cleaned, split, and hung up in the rigging to dry, to be afterwards sold in Melbourne. As the Girl stood on the deck, rod in hand, leaning over the bulwarks, catching barracouta, she positively shrieked with delight! Hauling up about three fish at a time, and all of them up to two feet and more long, the men took them off the line and rebaited the hooks for her.

They were convulsed with laughter to hear her squealing like a kiddie at her success. All she did was, just put the line overboard and pull it up again with several of these long barracoutas wriggling on it, for it had numerous hooks fixed some distance apart.

So voracious were these fish, that they could be caught by a bent nail with a bit of red rag on it. To get to Dunedin itself, we had to board a little cigar-shaped steamer, with a bow at either end, but no stern. In each bow was a rudder. She could thus travel backwards and forwards without turning. A very good contrivance for a narrow river!

The surrounding country was mountainous, and the City of Dunedin was situated on a hilly spot. It is the capital of the Province of Otago – (pronounced O-tar-go.). We stayed here some days.

PORT CHALMERS TO PORT LYTTELTON. January 23rd, 1866

We left Port Chalmers on above date.

Going around to the East Coast in the Pacific Ocean, we, after rounding Banks Peninsula, arrived at Port Lyttelton on the 24th January.

This is the port of the City of Christchurch, in the Province of Canterbury. It faces east to the great Pacific Ocean.

This is also the port that most Antarctic expeditions start from. A tunnel was being bored through the hills that separate the port from the city. It was undertaken by Superintendent Moorhouse, and was intended for a railway.

Lyttelton is steep, hilly, volcanic, and sombre, with no pleasant outlook, and hardly any shore. It is in reality the site of an ancient crater long since extinct; and the hills around are composed of lava beds.

Banks Peninsula, close by, contains extinct volcanoes. Inland, away back from Christchurch, a town was un-wittingly built over a volcanic crevice.

The houses and people had such a shaking up now and again, that the site had to be abandoned. The railway tunnel mentioned above was begun in July of 1861. The boring was finished on May 25th, 1866. As I was there on 24 January, 1866, it will be seen that it was then nearly completed.

It was opened for traffic on December 9th, 1867. It was bored through the wall of an extinct volcanic crater. Total length, eight thousand five hundred and ninety-eight feet – (8598 ft), of which 8128 feet was through volcanic rock.

The cost of the tunnel was £200,000. The rock was so hard, that specially-hard steel had to be made to drill it.

This shows what human determination and perseverance will do! There is no active volcano now on the Middle Island of New Zealand.

PORT LYTTELTON TO WELLINGTON January 25th, 1866.

Left Port Lyttelton on above date. Sailed northward, on the eastern or Pacific-Ocean side of the Middle Island, off Smoky Bay into the entrance of Cook Strait, across to the North Island.

We entered Port Nicholson and arrived at the City of Wellington on January 26th, 1866.

What is named Port Nicholson is really the harbor of Wellington. It is a large bay, circular in shape, with a diameter of quite ten miles, and is surrounded by mountains.

The entrance is narrow. On one side is Baring Head; on the other Pencarrow. One of the ranges visible from Wellington is named Rimutaka Range. Another is the Tararua Range, which latter stands seven thousand feet high and capped with perpetual snow. Wellington Harbor is a most interesting and pleasant place.

After getting through the narrow entrance, with high and sloping heads on either side, the wide bay opens out, with a long-range vista all around, finishing off with high hills in the background. It is really a magnificent land-locked bay.

The seat of Government had been shifted to Wellington from Auckland a few months before my arrival – in 1865, in fact. Owing to the hilly nature of the country surrounding this land-locked sea, the city of Wellington had little flat land to allow for development.

The town itself was composed of wooden buildings owing to frequent earthquake shocks knocking stone and brick buildings down. The chimneys were of brick, however. It is to be hoped the town will escape destruction by fire!

There is no tide in this beautiful lake-like harbor. At least I saw none, although at Port Nicholson the rise is five feet.

Just before we arrived at Wellington, sixty Maori prisoners of war escaped from a hulk lying not far from us in the bay. They had been captured from Werereroa Pah, and were guarded on the boat by British redcoats. [i.e. ‘Pah’ is a fort.]

One dark stormy night the Maoris opened a bow port and slipped into the water, all but two or three who remained behind to divert the attention of the sentinels, who were soldiers of the 40th Regiment.

This Regiment was stationed in Adelaide in the Fifties, when I was a boy.

I remember them well. They mounted guard at Government House gates on North Terrace. They were sent from Adelaide to fight the Moaris at the outbreak of the war.

From the deck of the South Australian in Wellington Harbor I saw a troop of uniformed horsemen gallop off from the wharves in pursuit of the escapees.

Some of the latter were drowned in their endeavour to swim ashore – the hulk was out about three-quarters of a mile from land, and the Maoris had no boat – a few came back, and two were shot; the balance got clear away.

The Maoris were called ‘Hauhaus’ and the white men ‘Pakehas’. Owing to the war, the interior of the North Island was (closed) to us. It was called the King Country. It included the active volcanoes and the Hot Lakes.

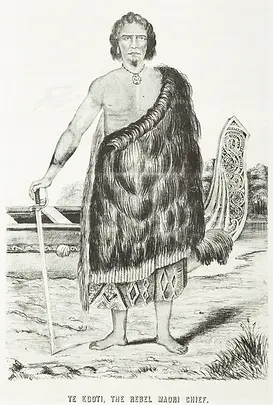

Many white settlers – men with their wives, sons, and daughters – who had advanced too far, were fiercely tomahawked by the Maoris. They were led on, or incited thereto, by a firebrand Chief named Te Kooti (pictured below).

The Maori War lasted from 1861 to 1870. It was raging the whole of the two-and-a-half years that I was in New Zealand. The war was wholly confined to the North Island, on which the City capital of New Zealand stands.

The capital of New Zealand was changed to Wellington as being more central. After that event, terrible fires occurred in Auckland city, the conflagrations being so fierce that the burning buildings on one side of a street ignited structures on the opposite side.

If I had had any money to spare at that time, I would have bought land in Wellington to hold for an advance. The city was then small; but in 1911 it had a population of fifty thousand people.

WELLINGTON TO NELSON

January 27th. 1866

We left the City of Wellington and passed through Cook Strait westward – from the South Pacific Ocean into the Tasman Sea once more. Cook Strait was an inspiring sight!

What Captain Cook’s feelings were when he discovered the division between the two great islands I could faintly surmise.

The rough, blue, waters, the distant lands, the moderate temperature, filled my mind with pleasure, and I pondered over the varied emotions, not unmingled with anxiety that must have been experienced by the world’s greatest navigator, as he ploughed his way, under sail, through these latitudes, away from all civilization, and at almost the antipodes of England.

The antipodes are at Chatham Islands, in the South Pacific Ocean. The islands belong to New Zealand.

Getting through the Strait, we rounded the various headlands, also D’Urville Island, passed across Charlotte Sound and Pelorous Sound, entered Tasman Bay, and arrived at Nelson, on the Middle Island, on 28th January, 1866.

Going around D’Urville Island was the nearest that we got to one of the finest extinct volcanoes in New Zealand. Had it been daylight at the time, we should have seen it, as it was only seventy miles away.

It stands eight thousand three hundred feet high, and is in the North Island, near Cape Egmont. It looks much like the Fuji Yama of Japan. It is an almost perfect cone, rising from a base nearly thirty miles in diameter. Showing what? – That it is deep-seated, and had always had a mild existence, without any violent eruptions.

Like Fuji Yama, the summit is covered with perpetual snow. Its name is Mount Egmont.

The entrance to Nelson, at the time of my visit, was a most uncommon one. A spit of land, or reef, of great length lay across the bay. The only navigable channel was in close proximity to some precipitous rocks or cliffs inshore. The steamer steered straight for these cliffs, then turned suddenly to port – (left) – into the stream at almost right angles, thence to the wharf on the starboard side.

The tide rises and falls twice daily, to the enormous height of fourteen feet perpendicular. Thus it can be understood that a very swift current is on the flow inward and outward through this narrow opening, except at high and low tides, and that vessels can come in and go out only on certain conditions of the tide.

This fact led, a year later, to the scheming of a diabolical plot, in which wholesale robbery and murder were intended. But just before its consummation, the schemers were caught; and three of them were hanged.

The men concerned were four notorious bushrangers and murderers. Their names were: Burgess, Kelly, Levy, and Sullivan. Their head-quarters were around my tent on the West Coast soon after I got there. I escaped all their meshes, but I may truthfully add that scores of other unfortunates were done to death by these lower-than-the brute creatures.

Strange to say, the revolver that I then had with me on board the S. S. South Australian was also worn in Nelson a year later by that very bushranger, Burgess when captured by the police in one of Nelson’s beautiful, grassy, and brook-flowing lanes. He had stolen it from my tent at Greymouth. I will give an account of these events later on.

Owing to the extraordinarily high tides in Nelson Harbor, small craft, such as boats and schooners, went in at high tide, beached in the mud, and then at low tide were overhauled and cleaned as they lay on their side on alternate days. It is one of the finest places possible for a graving dock. The tides could also be used for generating electricity.

We arrived there on a Sunday. All of us trooped ashore. Fruit was plentiful in the gardens. Nelson – nicknamed ‘Sleepy Hollow’ – is one of the most beautiful rural cities in New Zealand. Its architecture then was nil.

Its surroundings were charming – in the summer time anyhow! I knew nothing of its winter aspect. Purling, murmuring, rippling brook’s ran through its streets. The town is on a large plain, hemmed in – but not closely – by mountains, many of them in the distance snow-capped.

The Port is more than a mile from the town. At that time a narrow tramway with wood rails ran along a causeway and connected the two. The gauge was about ten inches!

We valorous two hundred – or, rather, a contingent of the two hundred – overran the place! Fruit gardens everywhere! Apricots ripe on the trees; cherries ditto. The latter were fine fruit. One large, well-kept, garden we invaded. It belonged to a benevolent old gentleman.

It being Sunday, he would not sell us any fruit; but he gave us leave to pick all the cherries we wished – provided we did no damage to the trees.

He informed us that he had the biggest collection of living birds and animals to be found in New Zealand. That seemed to be his hobby. He kindly invited us to inspect them. I am ashamed to say that only a few of us – myself amongst the number – had the courtesy to go around with him to have a look at his pets.

The other rascals made for the cherry trees post haste! I, and the few others mentioned, followed the old gentleman around while he explained his exhibits to us. Amongst those was, to my great astonishment, a pair of crows! I explained to him what an awful pest they were to stockowners in Australia, and expressed the hope that they would never be let loose in New Zealand.

He, however, did not take my admonition to heart, for the birds have since become as great a nuisance there as they are here in Australia.

Whilst on this subject, I may say there is now in New Zealand a terrible bird called the ‘Kea’ which attacks grown-up sheep. It alights on the sheep’s back, picks off the wool at the groin, then tears open the flesh and plucks out the caul fat near the kidneys.

The sheep runs about like a mad thing, and, jumping over precipices in the endeavor to escape its awful enemy, dashes itself to a pulp on the rocks below; or, after thorough exhaustion, lies panting on its side, while the horrible Bolshevik bird tears out its vital parts with its hooked beak

How about a Lord that ‘tempers the wind’ to the shorn lamb’ and ‘watches the fall of a sparrow,’ that silly ‘religious’ people rant about? Did he build that Kea to torture sheep? No! Every living thing on this earth – excepting herbivorous animals – devours one another.

Nature keeps the population down that way; and nature’s laws are unalterable. However, I am not writing about such abstruse subjects here.

I believe Nelson is now the seat of a great jam industry. Black currant jam ought to be one of its greatest products As we had a two-days’ stay here, we moved about and saw things. We came across a publican who had been in Hokitika – our proposed final destination. He had built a public house there.

Then he at once sold it at a profit of Three Thousand Pounds; and, taking no more risks, retired to Nelson. He was a wise man, and understood things.

Afterwards, in Greymouth, I saw a similar hotel sold for Twenty-five Pounds. And it was bought by a teetotaller from Adelaide! His name was Dale – a great temperance advocate, in season and out of season. He used the building as a carpenter’s shop and dwelling-house. Of this more anon.

Other gardens in Nelson sold us fruit. And we also gained information about the goldfields for which we were bound.

In the distance stood a mountain range which was to become the scene of a dire tragedy within the next twelve months in connexion with the Bushranging Gang I have mentioned. An account of their doings I give in a separate article. Quod vide.

The range was named the Maungatapu Mountains – pronounced Maungatap.

I enjoyed the sights of this beautiful village-capital, for it is the capital of the Province of Nelson. It was the very best time of the year – January – and the weather was perfect.

But a cloud arose on the horizon for me, for here at Nelson I lost my mate. He, in conjunction with myself, heard such dismal accounts of the West Coast, with its everlasting rains, floods, mists, rivers, jungles, and swamps, that he funked the job, and made up his mind to desert me on the quiet – to give the slip, in fact!

How I tracked him down to his brother’s house in Toi-Toi Valley, many miles in the interior, I have described in ‘Notes of Incidents’ in another book. He had Three Pounds sterling of my money on him, which I asked him to return. But after he had handed it to me, I gave him back a sovereign and a half, and we parted for ever.

Afterwards I used to send him half of my earnings because he was hard up. When I dropped it, that mate of mine never wrote to me again!

By the way, Toi-Toi Valley was named from the beautiful tuft-grass growing in profusion there. It is indigenous to New Zealand, and it seems almost identical with the pampas grass seen in many Australian gardens.

The tufts had great plumes standing high above a man’s head. After bidding my mate good-bye on that memorable afternoon, at his brother’s house, I started back for the ship, which was to sail in the night to suit the tide. The distance I had travelled inland that day was so great, that it was midnight by the time I reached the boat.

Upon nearing the harbor, I knocked up a tent-maker whose shop was on the causeway. He put a night capped head out of a two-storey window overhead and demanded who was there and what I wanted.

He soon came down upon ascertaining that I was a prospective buyer of a thirty-shilling 8 x 6 calico tent.

This transaction being completed, I got on board the S.S. South Australian again, and tumbled into my bunk, tired. When I awoke, I was out on the ocean, sailing and steaming. The date I left Nelson was the 30 January, 1866.

NELSON TO HOKITIKA

January 30th. 1866

On this date left Nelson for Hokitika on the West Coast. This was our final destination. The word is pronounced locally, Ho-ka-tik-ke, the accent on the penultimate syllable. I had to face the world alone once more. I was then seventeen years of age.

I must now look for another mate to accompany me to the goldfields. I soon found him in Mr. Harry Henderson, whose brother had been in a wholesale way of business as a confectioner in Adelaide.

Harry was much older than myself but seemed possessed of very little nous, as after events proved. Finding that I was a bloated capitalist with about sixty shillings to my credit, and a tent, he soon chummed up to me, and agreed that we should make our fortunes together as goldseekers; the more so as he himself was stoney broke! He hadn’t a stiver! Just a swag! Nothing more!

I myself had money in a bank in Adelaide, but would not send for it. Among other things they told us about the West Coast was that it rained eight days a week there. Therefore any tent would come in handy to protect Harry from the elements! But, did it? We shall see.

Harry was a Scotchman, as his name indicates. He was rather querulous than quarrelsome, with a very good opinion of himself – an exceedingly good quality in any man, by the way. That is what we call optimism. Otherwise he was not a bad sort. Gratitude, however, was a characteristic quite foreign to his nature, as will be seen when I unfold my narrative.

Yet I look upon his sojourn with me with a good deal of pleasure, for we were together in a very rough land, in very rough times, and had to look after ourselves.

Going around Cape Farewell, we got into a very choppy sea. The ship seemed to have half its length out of the water at a time – at one time the forepart, then the afterpart, at which time the big screw ‘raced’ for all it was worth, for there was nothing to check it then.

Captain Cook’s little tub must have bobbed about like a cork in those troublous waters. When the S.S. South Australian dipped into the trough of a great wave obliquely, the twisting and tilting she endured were very severe. I believe that mechanism has since then been invented to prevent the ‘racing’ of steamships’ screws when out of the water.

I saw the great cogwheel which drove the main shaft. The cogs of the wheel were made of a wood called hornbeam, let into the iron. It is of exceeding toughness. Steel on wood! and the great cog ran noiselessly. The hornbeam is a British-grown tree. Steel on wood left nothing but vibration of the steamer to cause annoyance to the passengers.

Cape Farewell was named by Captain Cook as he took his departure from that point of land on his first voyage of discovery in his little ship The Endeavor, of three hundred and seventy tons.

Captain Cook named two other points Cape Stephens and Cape Jackson respectively. A bay between Separation Point and Cape Farewell was called Murderers’ Bay by Captain Abel Jansen Tasman, who first discovered New Zealand in 1642.

Captain Cook was the first to discover that New Zealand was divided into two larger and one smaller islands. After a very rough voyage, we arrived abreast of the great mountain range named The Southern Alps (a mountain range extending along much of the length of New Zealand's South Island, reaching its greatest elevations near the range's western side) running parallel with the West Coast.

We reached Hokitika on the afternoon of January 31st , 1866. Mount Cook loomed up in the distance further south, snow-capped and draped in mists and clouds. The immense range extended north and south as far as the eye could reach.

There was a well-developed snowline, all above that being perpetual snow, and bare rocks of great magnitude. Below that line, dense vegetation, pervaded by dampness and ooze, reigned supreme. So gloomy was the outlook, so rough and stormy the sea, that no less than one hundred out of the two hundred never landed at all, but returned on the boat straight back to Melbourne! As I have said, it was afternoon.

There was no anchorage, and no time to be lost, All who intended doing so had to land that night or not at all. A little tugboat of two hundred tons – The Lioness – came alongside.

The billows rolled heavily. The passengers had to disembark on to the little tug. She went slowly up-up-up, then downdown-down, by the side of the big steamer. As the decks of the two became level, the passengers had to jump from the bulwarks of the South Australian on to the roof of the paddlebox of the tugboat.

Two sailors stood there, and, as the people jumped, grabbed them by the arm, leg, or whatever came handiest, and hauled them into safety. I threw my swag aboard, and followed it with a leap, for I was nimble enough. Then I turned and watched the others from the low deck of The Lioness.

Two ladies stood on the bulwark high above, awaiting their turn. One was elderly and thin; the other young and plump. Before they could jump, the little boat Lioness sank down-down-down into the trough of a wave; and there the ladies stood, high in the air, grasping their skirts, and supported by two sailormen. Of course, we down below all looked the other way – so as not to embarrass the ladies.

That was the only reason, for no man yet refused to look at a pretty ankle for any other! Our little boat slowly rose again, and the plucky girls jumped, and were hauled aboard from the top of the paddlebox. All intending to land were soon safe upon the deck of the Lioness.

Soon after this, a huge wave was observed by an officer on the big boat making our way from seaward A sharp order! Out at lightning speed came a sheath-knife from a sailor’s belt. The cable which held us to the steamer was sawed through instantly, the rope parted, and we fell off rapidly before the advancing wave had time to overwhelm us.

If you are looking for intelligence, you will find it among sea-faring officers and their men. Instead of returning to the steamer, our tug headed for the bar of the Hokitika River. The waves there were so big and curling, that our boat stood up like a prancing horse, and came down again with a spanking splash as we crossed the bar.

Then we were in safety in the calm waters of the Hokitika River. Steaming up this for the space of half a mile, we landed at the wharf. There is really no port. Nor will there ever be one. The ocean entrance is too steep and rough. By steep, I mean a sudden deepening of the ocean, with no anchorage.

At the time of my landing, there was a very large number of wrecked vessels on the coast near the entrance to the river. They had just missed the bar in attempting to get in, and were washed ashore, where they soon broke up, being unable to withstand the bumping they got on the shingly strand from the ‘curlers’ which rolled in unceasingly.

These ‘curlers’ were hollow, and of any height up to ten or twelve feet. I myself, later on, saw a large iron steamer wrecked at the mouth of the Grey River, twenty-five miles north of the Hokitika River. It broke clean in two, the stern half turning around to have a look at the other half, as they sat upon the pebbly beach, bemoaning their sad fate.

I walked around the two halves many times. From this may be gathered some idea of the great wash going on eternally on that weather-beaten coast, facing as it does the whole stretch of the great Southern Ocean. The town of Hokitika was the biggest and most important on the Coast just then. It was less than two years old.

The Goldfields of NZ 1866

The goldfields of the West Coast had been discovered only a little more than a year when I arrived. There were no inhabitants before that, excepting a few Maoris who had been driven down from the north along the coast through tribal disputes.

Revell Street was the most important thoroughfare of Hokitika The place was in an embryo stage. Shops and other structures were being extended northwards in that street for a length of two miles.

The town was on the north bank of the river. It ran parallel with the coast, but about half a mile back. Since then – in 1914 – the waves encroached upon the street and washed many of the shops away. The erections above mentioned were composed of a framework of wood, resting on piles placed in the ground.

On the outside, the buildings were of weatherboard, the divisions between the rooms a kind of rough calico called ‘scrim’ – a fabric much like cheesecloth. This was papered. One could hear everything that was said in an adjoining room.

The roofs were of corrugated galvanized iron. Some buildings were of iron in place of weather-board. Every other place seemed to be a grog shop. There was no restriction of public houses then; no talk of prohibition. As many licences were granted as were applied for. The building of new ‘pubs’ was only stayed when it would not pay to erect them.

Before proceeding further with my narrative, I must continue the history of the S.S. South Australian after I had bidden her adieu off the West Coast and in sight of the great Southern Alps and Mount Cook.

During her next voyage or a voyage or two afterward, she struck a rock in New Zealand waters and foundered. It was, fortunately, calm weather. She hit the rock, and stayed there till all the passengers and crew were rescued.

Then, when a steamer was sent out to salvage her, it was found that the waves had washed her off the rock, and that she had foundered, leaving no trace.

My mate – Harry H. – and I swagged it through the whole length of Revell Street, striking north, as we had decided to make for the Grey River. Another man who had no tent I took pity on. I invited him to accompany us and share my tent at night.

It had been raining all the time we were disembarking, and it was still going strong as we started northwards. The whole country was soaked, all vegetation sopping wet, and dead wood and kindling sticks were soaked to the core. We decided, money being short, to make straight through the town and camp some distance away on the coast.

I purchased two or three quarter loaves – four-pounders – of bread, and some bacon, also cheese. My newly-found mate – H. H. – growled incessantly, like the rain that was falling. And he growled at my extravagance in buying the bacon – with my own money! He had long since come to his last shilling.

I gave the ungrateful fellow shelter and food. The stranger also lived on my spare bounty, and had the shelter – such as it was! – of my tent during the nearly three days we footed it on that very inhospitable coast. But he was a very nice, quiet fellow, and showed his gratitude. I regret that I did not ascertain his name.

The seashore consisted of shingle – i.e. big pebbles and small pebbles, with occasional slabs of rock, all much waterworn. I took my boots off and slung them around my neck, jumped or stepped from stone to stone. Those boots were the pair I referred to in the account of my Australian journey with sheep in the Far North. As I shall write a separate article detailing this journey, I will merely summarise here.

At dusk we erected the tent above high-water mark on the fringe of a dense scrub which came down to that line all along the West Coast. Everything was so thoroughly soaked, that we were unable to light a camp fire. We had to drink cold water and eat dry bread and cheese.

I getting into my blanket for the night I put the bacon underneath my head. In the morning it was gone! The rats had pulled it from under my head as I slept. I found a portion of the rind outside the tent next morning. No doubt a judgment on me for my extravagance!

The flood waters rushed down swiftly, and carried great weight with them. We camped on the Hokitika side of the Arahura on the first night. We waded through all the streams safely, although at one of them H. H. thought he was a ‘goner’. He being the last man, the pebbles broke away from under his feet, and were carried down stream.

As the disturbed stones shifted their location through the force of the current, a big curling wave followed Harry up with a roar, seemingly intent upon devouring him! However, the stout poles kept us upright, and nothing untoward happened.

Our second camp was south of the great Teremakau River. This is the biggest river on the Coast. During the whole of our day’s journey it rained incessantly. We had an arduous day, although a short mileage. I jumped from pebble to pebble, with my boots still round my neck. We were all well damped by the rain during the day and by the spattering through the thin calico of the tent throughout the night.

On the morning of the 2nd February, 1866, we left this camp, and upon reaching The Teremakau found there was no getting over without a boat. The river was more than half a mile wide, divided into three streams, but emerging into one near the mouth. Fortunately a boat was there, and we paid half-a-crown apiece to the boatman to take us over.

The stranger with us observed, with much disgust, that ‘You can’t open your blanketty mouth in this blanketty country without being charged half-a-crown for it!’ I also expressed the opinion that had that been the River Styx, Charon the boatman would have taken us across gratis as ‘deadheads.’

My beautiful Marianne has crossed that mythical river since I first penned those lines, and disappeared in the mists beyond, leaving me behind, deserted and alone! – – –

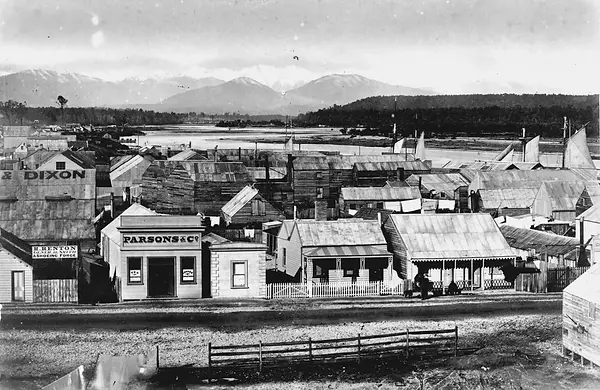

After passing the Teremakau River, we travelled onwards, eleven miles, crossed the Saltwater Creek, and after another mile, arrived at Greymouth in the evening. The distance travelled that day was fourteen miles.

This was quite equal to a twenty-eight mile tramp in Australia, as jumping from pebble to pebble is a monkey’s game, and trudging over heavy shingle is very tiring. Sometimes the pebbles were two and even three feet long.

Then the going was easier. There were occasional patches of sand. I, in common with the others, had all my worldly goods upon my back, wet blanket included, and wet tent also, rolled up in the shape of a swag.

My thoughts upon reaching Greymouth were mixed. I was a stranger in a strange land – a land vastly different from the Australia I had been accustomed to. Through the gorge east of the town, the Southern Alps showed, capped in everlasting snow.

At Point Elizabeth, five miles north of Greymouth, a small coastal range comes down to the shore. At Greymouth the same range is about one mile inland. There the river comes through a gorge in that range.

On the south bank of the river, at the foot of the range, the town of Greymouth stands. Just there the range is only six hundred feet high. It is steep, and covered to the top with tangled vegetation. The rock of which it is composed is carboniferous limestone – a sure indication of coal deposits.

Everything was wet on the Coast. Mud, water, lagoons, swamps fringed with phormium tenax (New Zealand flax) abounded. Equally abundant also was the Toi-Toi grass, with its beautiful plumes. The vegetation was so dense as to be impenetrable without the aid of axe and knife.

And the rain was still falling when we got there! No wonder one’s spirits were damped also. I was then on absolutely almost my last sovereign. Everything was dear. Eggs, three shillings a dozen – they had been six shillings. -: meat one shilling per pound; Wellington boots, forty-two shillings a pair; Crimean shirts (woollen) eighteen and six each. But I had a tent to sleep in, and wood and water cost nothing.

But I knew that this Number Two Mate of mine would desert me on the first opportunity. He was built that way! And he did, leaving me to battle along on my own. Of this more hereafter.

Before going further, I will record a historical incident connected with the supplying of the Maoris with contraband of war that occurred about the time of my arrival at Hokitika. The hero – or I should say adventurer – of the affair was a notoriety named ‘Bully Hayes.’

Extract: – ’Recently, some West Coast incidents were brought to light. One of them was a visit to Hokitika in 1866 by Bully Hayes, in his piratical craft, which was in due course inspected by a New Zealand Customs officer.

There were tons of gunpowder stored on board, and when the Customs officer went below with a lighted match, Bully Hayes and some of his men, knowing the nature of the cargo, moved well out of the way. Fortunately the officer did not discover the gunpowder, and the gunpowder did not discover the match!’

The Customs officer used matches to inspect the Rona, and threw the spent matches about. They were the old post and rail kind, large, with brimstone heads. He actually threw lighted matches on to a tarpaulin which covered twenty tons of gunpowder. Bully Hayes said he was never so near hell in his life!

The cargo of gunpowder was for Te Kooti, the rebel Maori chief, to be delivered to him on the North Island. Te Kooti was the leading spirit of the Maori War raging at the time. Hence the villany of Bully Hayes in supplying him with ammunition.

Upon arrival at a new place, the chief thing is to find a camping-ground We pushed our way in the mud and slush through the new Town of Greymouth, along the two quays by the river, right up to The Gorge where the Grey volumes through, to be lost after another mile in the curlers on the beach – a shore facing the great Southern Ocean. .

At the spot where we pitched our first camp, the post-office was afterwards built. It was a nice little flat, with water handy, and sopping-wet wood all about. There we erected our tent temporarily until we could find a more secluded site.

It had been raining all the time since our landing. Of this we had the full benefit; both in having swift streams to wade through, and in being wet through day and night.

The Grey River we did not cross, as Greymouth is situated on the south bank. The town of Cobden was on the North bank, near the Gorge; but it was only a little village. The mouth of the Grey River was wide and deep.

Being short of cash, I obtained a fishhook, got a line, and also made a net, and proceeded to fish in the river to avert starvation. With the net I obtained whitebait in abundance; and I boiled them down into soup. It was delicious and nourishing. I caught fish occasionally with the line.

One day a little robin redbreast sat on my rod most of the time I was fishing. Upon going to my tent that afternoon, I lay face downward, when another robin came in and sat on my shoulder. I took the little chap in my hand, where he nestled comfortably. Going out quietly, I closed the flap of the tent and left him inside; but upon returning, I found him gone.

Being now alone, I determined to strike inland and prospect as a ‘hatter’. I spent almost my last shilling in buying food to take with me. I obtained four quartern loaves of bread = 16 lbs; four pounds of cheese; some bacon; and some coffee and sugar. Then I packed up.

It was still raining! I had not seen the sun for many days. My money now being about flown, I could stay no longer in the town. Accordingly, with no one to see me off, I shouldered my swag, weighing over one hundred pounds, and made a start.

My tent, my blankets, and all my wearing apparel were wet; and when soaked with water, those things are weighty.

I made my swag up into two rolls – one for my front and one for my back, vertically, to prevent my being pulled back by the ‘lawyers,’ or wait-a-bit thorns.

The track I selected was not more than two or three feet wide. It went through jungle so thick, that nothing could be seen a few feet away. In addition to this double swag, upon the back half of which was fixed a pick-head, a tomahawk, and a large prospecting dish, I had a shovel in one hand and a pick handle in the other.

Leaving the Grey River on the left hand I struck out on the right along the base of the six-hundred-foot range covered with trees and creepers to the top. I never set eyes on the range itself, but knew it was there by the slope. I was fortunate in keeping out of the marshes down below.

It rained all the while, and big drops fell through the forest overhead. I was soon wet to the skin with combined water and perspiration, for it was the heaviest track I had ever been on.

It would have been killing enough without the load. It was doubly so with it.

Back to Greymouth

My first big obstacle was a huge tree lying across the track. On my first essay at mounting it, I fell backwards right on my back into the mud. That was an advantage: no fear of hurting one’s self by a fall! A nice, soft, cushion always ready to receive you!

By making a tremendous rush, I at last scaled the obstruction, and dropped into the all-embracing slush on the other side.

On higher ground, where the undergrowth was a trifle thinner, I met three men coming down to the coast. The leading man walked for perhaps eighty feet along a fallen tree-trunk that was as straight as a ship’s mast. Getting off the end gingerly, and stepping on to what looked like the hardest ground, he began to sink into the mud. His mates pulled him out.

They advised me to go back. But I went on. I crossed many rapidly-flowing creeks, full almost to the top of their perpendicular banks. Across each I straddled upon a single fern-like trunk that had been felled and thrown from bank to bank.

Some of these fern trees grow to a height of sixty feet. I saw some forest trees – either Kauri or white pine – with trunks up to ten or twelve feet in diameter; but they were old and decaying. Some of them had been embraced by a peculiar creeper named ‘The Rata’.

This climber, as I should call it, had gradually grown around its prey, till at last the whole circumference of the trunk was covered with a solid mass of wood a foot or more thick, which squeezed it tighter and tighter till the noble tree had died, the creeper standing up in its place like a huge cylinder, being now a tree itself to all intents and purposes.

Other tall white pines had climbers resembling great cables six or nine inches thick climbing up them. The stalks of these climbers swayed about like long snakes hanging from limbs one hundred feet high.

The supplejack was in evidence everywhere. It is dark-green in color, and of the thickness of the new wood of a grape vine, but with longer joints.

The ‘lawyer,’ or ‘wait-a-bit’ thorn was a creeper with sharp hooks on it that pulled one backward as they unceremoniously hooked themselves into one’s clothes. The word ‘lawyer’ was a sarcasm of the diggers. ‘Wait-a-bit’ more aptly described it. I was pulled down by it several times that day, and accordingly had to wait a bit, willy nilly.

By and by I came to a rather wide creek, with the usual torrential stream and a single trunk of fern tree thrown across it from bank to bank. I was just about to rush across this little bridge standing up, and chance falling in, when, above the din and roar of the water, I heard a voice urging me back.

I stopped, looked up, and saw a man on the opposite bank gesticulating, and heard his shouts warning me not to cross standing, but to do the sliding and shuffling act. He pointed out the danger of my toppling into the stream, when nothing could save me, loaded as I was.

So I desisted, and flinging my pick-handle and shovel across, ignominiously straddled the narrow fern tree once more – with my legs dangling in the current, the balance of my heavy swag on my breast and back – and shuffled and wriggled across.

It was still raining. But as I was wet through, it did not matter about my legs dangling in the running water. There are lots of good fellows in the world. This man tried hard to deter me from advancing into that wild chaos of vegetation, roaring waters, and underfoot slush. But I was determined to go on, and I did.

I was seventeen and a half years of age then, and I was just gaining experience – experience that makes one wise. I had no watch and the sun was invisible. The rain never ceased. I could not unroll my swag to have a feed. Thus I went on till dusk, when I came to an open glade, caused by the fall of either a giant Kauri or white pine.

A dank smell of decaying vegetation permeates the whole atmosphere of the West Coast forests. In places the decaying matter is six feet deep. Pitching my tent on a large heap of dead fern leaves – not by any means dry – I found I was too exhausted to even light a fire!

Water was running beneath fallen timber and undergrowth. It could be heard but not seen. However, I searched, filled my quart pot – for I still stuck to that Australian utensil – and quenched my thirst with cold aqua pura. I then had a little bread and cheese.

I fastened the edges of the tent down tightly into the fern leaves upon which it stood, and, tying the door flaps around the upright post, I thought I had done all possible against an invasion of the dreaded mosquitoes. Then I lay me down upon my little bed, exhausted, for it had been a strenuous day, with so heavy a load and so bad a track. I was not knocked up by any means – just tired out.

I had gone only about eleven miles after all, but they were leagues to me. It was one of the hardest day’s work I had ever done. My four pounds of cheese and sixteen pounds of bread made one an excellent pillow as I lay there enjoying the luxurious rest. In the fading light I heard mosquitoes humming! They were inside the tent! I was horrified! But there was no help for it. They had arisen out of the bed of dead fern leaves! The irony of it after all my precautions!

Then, to make things still nicer for me, before it got dark I saw the shadows of strange animals that were climbing over the outside of the tent. The animals were rats! Hordes of them! They had smell the cheese. As I lay on my back, I knocked them into the air with right-handers and lefthanders as they clambered over the tent seeking an opening. But it was no use. There were too many of them. And I was so thoroughly exhausted, that even this attack by an army of rodents could not keep me awake. With my arms still whacking at them, I went off into a peaceful slumber.

I slept without so much as a movement till daylight, when I woke refreshed and quite recovered The recuperative power of youth is great! The rats had got in, having knawed a big hole in the calico. All night they must have been wrangling over my body for the cheese. The cheese was non-existing. The whole four pounds weight of it was gone. Not even the smell was left, let alone a crumb.

Many years after this, while in Australia, I read an account of an invasion of rats at a certain spot in New Zealand, and it was regarded as a great mystery as to where they came from. I knew! The uninhabited forests of the West Coast were full of them.

During the night I had also been doped by thousands of mosquito lances. The roof and sides of the tent were black with the pests. I had to turn the tent inside out to get rid of them, also shift my camp from the fern bed.

I prospected in the locality, and sank many ‘duffers,’ but got only the ‘color’ of gold. The bars of the creeks were flooded, and I could not get at them. These bars are the places to make for in prospecting for alluvial gold, as they catch most of what is washed down by the current.

If I had had a mate, we might possibly have made good wages. I did not see a soul – I mean a body. Nor did I find any tracks, or signs of occupation anywhere. So one day, when my bread gave out, I started back for Greymouth, a lighter but more experienced youth.

I got back without mishap. The question now was, What should I do? I hadn’t hardly a nickel in my pocket. I had a balance in the Savings Bank in Adelaide. But that was out of my reach.

I had had two-and-a-half years’ experience in the Register newspaper office, Adelaide – one year at daywork, and one-and-a-half years at night work – and had learnt the compositor’s art, and almost everything connected with newspapers.

I also knew all about paper-ruling and bookbinding. These latter arts I had learnt in Leigh Street, Adelaide, with Mr. W. Rose before I entered the Register office. But I had been away in the Australian Bush for two years, and did not know whether I was still competent – whether, in fact, I had forgotten the boxes of the type cases.

A newspaper had just been started in Greymouth. It was named the Grey River Argus, and was a tri-weekly, the publishing days being Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays.

The office then was in a canvas tent below Boundary street. I studied some posters in the shop windows on Mawhera Quay, and wondered if I could ‘set them up’ creditably. I have ‘set up’ thousands and thousands since that hesitating period!

At last I mustered up courage to apply for a billet as compositor at the Grey River Argus office.

I did so, and was taken on at once.

Next Page: The Grey River Argus