H H Tilbrook's Education

Growing up in Wales

and Learning in S.A.

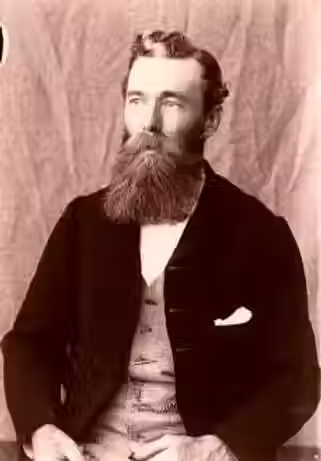

Henry Hammond Tilbrook became the founding editor of the Northern Argus in 1869, the newspaper of the Clare Valley, which was published until 2020.

Trained as a journalist at the Adelaide Register, he kept reminiscences in seven voluminous journals, now kept at the State Library of S.A.

Tilbrook was born in Llandudno, Wales, on June 14, 1848. His father was a gamekeeper originally from Weston Colville, Cambridgeshire.

-

When Tilbrook was about six years old, in 1854 the family sailed to South Australia on the Albermarle.

-

He worked for two years as a typesetter at the Register in Adelaide (1861-3)

-

as well as working as a lamb minder for a short time, for Sir Thomas Elder (1864). Tramped all over the same area (1865). Grocery delivery in Glenelg.

-

Worked at Ooraparinna Cattle and Sheep Run, far north of Wilpena (1865).

-

Enticed by the gold rush at the time, Tilbrook moved to New Zealand in February 1866 to try to make a living prospecting.

-

After having no luck with gold (in the rain), he moved on to work (1866-1868) for the Grey River Argus in Greymouth (first published 1865).

Shortly after returning from New Zealand, H. H. Tilbrook founded the Northern Argus newspaper in Clare, first edition, 19 February 1869.

– ANTECEDENTS –

I am not a quarrelsome individual, or a fighting one. My paternal grandfather was a powerful, active man, and a fighter if the necessity arose.

He kept an inn at Cambridgeshire, England, in the early part of 1800 – that is, the beginning of the Nineteenth Century, – and had wagon teams travelling between Cambridge and London, a distance of fifty-two miles, in the days before railways were in vogue. He also had a farm.

He was a man of great determination. In stature he was not quite six feet tall, of powerful but active build, and straight as an arrow. He wore the usual light-fitting knee-breeches then in fashion.

Standing before the fire, my father told me he had often noticed how perfectly straight and well-proportioned were his limbs. He fought many a battle with his fists in those rough days, and was never beaten.

He lived till he was eighty-three years of age, and but for the early decease of his wife would have been a rich man.

My father also learned the "noble art of self-defence," and had to make use of it on several occasions – He always spoke of his battles reluctantly, and I had to draw the tales from him bit by bit.

When sixteen, he heard a man threaten to fight his father. 'Fight my father!' he said in amazement – "Fight my father! You'll have to come out and fight me first!' And go out and fight they did.

He gave the fellow such a thrashing, that whenever they met afterwards, the man who had been spoiling for a fight invariably went on the other side of the street.

Another time, when in charge of one of his father's teams, while staying at a wayside inn, a bully picked a quarrel with him. The bully tried to take him unawares, and sailed down upon him while seated. But my father, being exceedingly active as well as strong, gave him one-two between the eyes, which laid him senseless on the floor. Then the fighting fire and the latent determination in him got the uppermost, and he offered to take any of them who didn't like it – one at a time or all together. No offers!

When the man came around, he was like the Soudanese nigger whom Sir Samuel Baker struck in the same spot with his fists when the nigger attacked him with a knife – where the nose and both eyes had joined partnership. I forbear giving any more of his exciting experiences in that line. He never fought except to defend himself.

He was well educated when a youth, and was very bitter that his education was not put to better use. I still have two of his schoolbooks – dated 'West Wratting, 12th May, 1830 – 11th Jan. 1831' – and they are a marvel of neat writing and intricate arithmetic, all written with quill pens, which the schoolmaster cut out of goosequills with a penknife.

His brothers – my uncles – were also quiet but determined men. Whilst seated, John Tilbrook was once struck a terrific back-handed blow across the mouth by a surly fellow whom he had caught poaching. This seemed to raise Cain in him to such an extent that he went for his assailant, thrashed him within an inch of his life, and left him apparently dead on the ground. He recovered however.

This was told me by my uncle, Mr Tom Stalley, who was present and witnessed it all. Mr Stally married my aunt, Ann Tilbrook.

Another brother – Jim – had charge of some duke's estate, and the Prince of Wales – afterwards King Edward V11 – made him a present of five sovereigns every time he went there, which was very often.

In an Illustrated London News a picture was given of 'Tilbrook Cottage' where he resided. I think it was at a place called 'Long Bottom'.

One night, Jim heard shots. Getting up, he took with him his man Sam and tackled the poachers – for such they were.

Approching two men, one of them pointed his gun at Jim and said that if he advanced nearer, he would be shot. But Jim was not to be cowed. He went up to seize the poacher, when the latter fired at point blank range, and half of Jim's face was blown away – 'Sam' then gave the poacher a dose of shot in his seat of understanding as he was making off, which dropped him.

'Sam' then chased the other poacher, who got away, but was afterwards apprehended. 'Sam' came back in time to see the first poacher hobbling off on crutches which he had improvised out of tree branches, and took him in charge. He was transported for fifteen years.

Uncle Jim recovered, and his employer made him a present of Five Hundred Pounds sterling.

Of my mother's family I know little. My mother herself was a very skillful woman. She was a Nunn. My father told me the skilfulness ran in her family.

He had seen her brother, William Nunn, fill his pockets with pebbles, and go into a paddock where a vicious bull grazed. When the bull made for him, he stood his ground and hit the animal wherever he chose with the pebbles, until the bull had enough of it and cleared off.

I have learnt that many of the Nunn family are rich, and that there is one in Australia – either Melbourne or Sydney – who has an extensive business.

My father was an expert shot with the gun, never missing, however difficult the shot. He shot on the wing or at a running target. Rabbits running from bush to bush he shot from the hip. He told me this wrinkle – to always shoot with both eyes open. This showed a double sight on the gun barrel, and I think it was the right hand image he used – but am not quite sure now. But it could easily be tested on a stationary target.

Our house at Llangforda (or Llangvorda) on the border of Wales where I was born, was two-storied, of nine rooms, My mother had two servants – one named Ann, and another to mind us.

I remember that Ann one day climbed the sloe tree, and fell out and broke her arm. A terrace in front of the house overlooked the orchard – There was no verandah on account of the weight of the snow in winter. There was a big dog-kennel or enclosure.

When my father entered this, he always took a stout whip in his hand, as, he said, his life would have been endangered otherwise.

Mary Roberts, a miller's daughter, used to come and play with us. We loved her!

The mill was at the brook below us. The millpond was fed by this rippling brook. Every time the pond was emptied, the miller sent us heaps of fish.

I have stood and watched, with dread, the big, sombre waterwheel revolving with a continuous roar, and listened to the water splashing down. Those sort of things will come again yet – water wheels where running water is abundant, and windmills where water is scarce.

My brother George was an obstinate boy. Skating one day on the ice-covered millpond, the girl told him not to go on the blue ice. But that was where he went, with the result that one leg went through the thin ice. The girl got him out somehow.

In winter we snowballed each other, and thus made ourselves warm. When the bleak north wind blew from the Pole, or the north-east wind from the Continent of Europe, we buried ourselves beneath the snow to keep warm.

In the summer we gathered daisies, buttercups, cowslips, and other flowers, and made chains and balls of them.

A pony that we owned was a trickster. He undid the gates, chased the cow into the turnpike road, and then drove her back again. He would pretend to gallop over us in the fields. But we knew him, and did not move. When he got near, he would stop suddenly, then prance about like a little kid. My father was reluctantly persuaded to part with him for the sum of Forty Pounds to some circus people, much to his regret afterwards.

One day, standing at a gate that opened into the woods, I saw a fox pass quite close, in front of me, but it did not see me. Another day I saw a fox that was caught in a trap fixed in a wall that was built around one field, and told father.

It was cold during winter! Sleeping in a bedroom upstairs, I was brought down in my nightie in the mornings and placed in the chilly fireplace till the fire was lit.

Big oak trees were felled for their timber and their bark. While being grubbed, ropes were placed on the topmost branches, and I used to put in a pound or two of my weight in helping to haul them down. Then wooden mallets were set to work hammering the bark, till every particle was stripped off. This was used for tanning purposes. It makes the best leather.

We had a donkey that we boys used to ride. We often went into the sandstone hills of Wales to get sandstone for mother to clean the knives with. And in those hills we gathered beautiful snowdrops also.

A man named Francis lived near our beautiful brook, and I thought it was strange that it was either a man's or a woman's name – the woman's being spelt Frances.

Schooling in Adelaide

-

Henry Tilbrook was a chorister in his youth at Christ Church.

-

and was educated at Mr. J. L. Young's and Mr. Elliott's schools in Adelaide.

At one period I went through a course of Navigation under the personal tuition of Mr. J. L. Young at his well-known Academy on the corner of North Terrace and King William Street, Adelaide where the Bank of New South Wales now stands.

A shrewd, clever little gentleman Mr. Young was!

I did not understand the Rule of Three then, and that was one thing I learned from him.

(The Rule of Three is a writing principle suggesting that things presented in groups of three are more satisfying, effective, and memorable than other numbers. It's a common technique used in various forms of communication, including storytelling, rhetoric, and even everyday language.)

I bought a copy of Norie’s Epitome of Navigation from him for one guinea. He was very conscientious, and he taught me thoroughly – plane sailing, taking the latitude and longitude by both land and sea, and the various operations and calculations connected with the science.

He also taught me the use of logarithms – a very simple and short way of doing long sums.

The British Admiralty publishes, four years ahead, the Nautical Almanac, showing the positions of all the important heavenly bodies right up to that time for the benefit of mariners going on long voyages, and for scientists generally.

By its aid, mariners find their way over the oceans. All eclipses, and all celestial phenomena, are there published four years ahead, for all nations to use.

And it was by an issue of the British Nautical Almanac that our calculations for latitude and longitude were made I went through this course of navigation because I wished to learn how to find the latitude and longitude both on land and sea.

At sea, in order to ascertain the latitude an ordinary quadrant only is required. But for the longitude, a sextant is necessary, as it embraces a wider angle.

On land, however, a quadrant is useless.

A sextant is indispensable, because an artificial horizon of quicksilver is necessary, thus giving double the angle obtaining at sea.

Of course I bought the necessary sextant and artificial horizon, but have since sold them.

I at one time wished to go exploring. Hence my desire for the above knowledge.

It is men of big minds – supermen, really – who have brought all these things down to an exact science, for the use and benefit of mankind generally.

After going through this course, under the careful tuition of Mr. J. L. Young, I could really, on an emergency, have navigated a ship across the ocean.

ADELAIDE TO PARATOO – 1864

‘Lives of small men all remind us,

We can write our Lives ourselves,

And, departing, leave behind us

Some fat volumes on the shelves.

– Per Longfellow

In the lives of most men there’s a tale to unfold

Which it is selfish to keep to themselves.

They should take up the pen, ere getting too old,

And some fat volumes leave for our shelves’ H.H.T

People who live within the narrow horizon of our cities know little, as a rule, of the topography or natural characteristics of the Australian Bush.

They do not like the discomforts of camping out; of rough travelling, be it on foot, on horseback, or by mail coach; or of living upon Bush fare.

No exhilarating thoughts such as those that thrilled the breasts of explorers whilst gazing upon a vast expanse of new country are entertained by those who, always living amongst their kind, have not enjoyed the solitudes and the beauties of Nature. For even the Australian desert is a thing of beauty.

When a boy, I took a most romantic interest in any newly-discovered land, and especially the interior of Australia.

I was not happy until I had made a practical trial of a life in the Bush. And it was not long ere I became disillusionised. For romance wears off as we grow older. Then we prefer the life of the city, with its comforts, luxuries, and attendant pleasures and diversions.

There is nothing in Bush life unless you are the ‘Boss’, or an explorer of new regions.

I started in a very good way to have the romance knocked out of me.

-

First, I went up as a lamb-minder;

-

then I acted as a horse-driver at a deep whim-well (possibly Yanyarrie Whim Well, a well in South Australia likely used for water supply;

-

and also tramped many hundreds of miles with ‘Matilda’ (with one's belongings in a "matilda" (swag) slung on my back, never having more than two meals a day,

seldom obtaining water to drink between the hours of sunrise and sunset. -

Afterwards things were a bit more romantic with me, when I became under-overseer while still a boy.

Then my duties included-

mustering cattle, riding around on horseback the whole day long;

-

looking after sheep, cattle, horses, shepherds;

-

counting-in or counting-out flocks;

-

poisoning dingoes;

-

camping out alone and sometimes with others, in the wilds;

-

shooting kangaroos, euros, and other game;

-

and keeping an eye on the Blackfellows, who were then very numerous.

-

Notwithstanding the romance, however, these things also had their disadvantages. But I did not think so at the time, being young and enthusiastic.

Youth mostly takes things as it finds them – philosophically and in a matter-of-fact spirit.

Then there was the love of adventure to hold one up and urge one on.

As a life-occupation, however, a solely-Bush existence is not to be desired. Coarse and tasteless food is a drawback which one does not become enamoured of.

I will now give some of my experiences of Bush Life, starting with the year 1864, my age then being somewhat over fifteen years.

I was engaged by Mr Thos. Elder – afterwards Mr Thomas Elder – who was very kind to me. But I was deficient in one accomplishment. I had had but little experience in equestrianism.

True, I had ridden a bit. And once I rode a horse, bareback, down the brow of Montefiore Hill, from Jeffcott Street; when the horse bolted, and I fell over his head, and was partially stunned. Even then, I had jumped up before I had recovered my senses, and gave chase to the animal, and with the aid of a sand-carter on the Torrens eventually caught it.

I suspect, now, the sandcarter did most of the catching! As I remember offering him a shilling if he could catch it. First there was the fall – then a blank – then the sandcarter – another hiatus – then I came to, and found my father bathing my damaged head with hot fomentations.

It seems I rode the horse back after all, although I was unconscious of the fact. But that kind of horsemanship did not fit me for a Bush life!

I also, when twelve or thirteen years of age, drove a grocer’s cart in Adelaide, my first adventure in that being on a busy Saturday in crowded Rundle street. The grocer was Mr Sharland. His shop was on the very site where Kither’s shop now stands. [In pencil] Now (1935) next to Dell’s 5 storey]

Mr Thomas Elder kindly informed me that if I would learn to ride, he would place me on one of his stations. I used to interview him at his office in Grenfell Street, where he worked as hard as any of his clerks.

There was a grocer, named Lammey, in North Adelaide, who owned a grey horse. I stipulated with him for the use of that charger for one hour a day at one shilling per hour. The reason why I had leisure to ride a horse in the day time was that I was then employed in the Register office on night work, in the composing room, working generally till two, three, and four o’clock in the morning.

I obtained my father’s watch, got my grey charger, – saddled, bridled, and mounted him – and galloped up and down the hilly parklands opposite LeFevre Terrace and Medindie, over the rough limestone quarryings that were being made there.

I picked out all the broken land I could find. There no fences on the parklands then. So I had free scope to go where I liked.

I rode over the stacks of limestone, into the trenches, and out again, at full gallop. And I also learned to trot.

This was all good experience, and I found it quite exhilirating. When, however, I got into the rough Bush work on horseback, I found my knowledge woefully lacking. But that was soon remedied with practical work.

Having become a rider, Mr Elder sent me up to Pandappa and Paratoo stations in the North-East.

Above: Sir Thomas Elder GCMG (5 August 1818 – 6 March 1897) was a Scottish-Australian pastoralist, highly successful businessman, philanthropist, politician, race-horse owner and breeder, and public figure.

Amongst many other things, he is notable for introducing camels to Australia.

He became associated with Peter Waite in the Paratoo run in 1862, in the same year he bought Beltana station, and eventually became the owner of an enormous tract of country.

ADELAIDE TO BURRA BURRA March. 30. 1864.

I left Adelaide on the 30th of March, 1864 for Pandappa and Paratoo – the one, One Hundred and Sixty Miles and the other One Hundred and Ninety Miles from Adelaide.

The only railway lines open at that time in South Australia were the Port Adelaide line and the Kapunda line – the latter, Fifty Miles in length. The Kapunda Copper Mine was then in full swing. Things were lively there.

Mr Elder had given me fifteen shillings as pocket-money, to help me on the way. He also engaged two other young fellows with me. One was a lawyer’s clerk; the other a parson’s son named Owen. To these he also advanced a similar sum.

We three chummed together.

I myself had been working for two and a half years in the Register office – Adelaide’s first daily newspaper – and had learnt a good many things there in all departments. And I was already an accomplished compositor.

As half of my years had been night work and the other half day work, I had had the run of the office from the pressroom, machine room, composing room, job-printing room, to the editorial and reporting rooms.

I had also been ‘proof’- reader, with Mr Cooper. That is, I read out the ‘Copy’ to him and he marked all errors on the sides of the ‘proof’ sheets.

I was also ‘galley’ pressman. And, as I had plenty of time on my hands, while on day work, I used to put in the ‘dis’ for many compositors. That means, I put back into the ‘cases’ for them, a couple of columns of type a day – say about sixteen thousand separate letters – minion and brevier, sometimes long primer.

One of these compositors was a brother-in-law of a proprietor – a good-tempered, handsome fellow, but addicted to a very bad habit prevailing amongst many ‘comps’ in those days. – i.e. lifting the little finger! (Lifting the little finger while drinking tea, once considered a sign of elegance, is now widely regarded as pretentious and rude).

He used to promise me sixpence for distributing two columns of type for him into two cases, ready for him to start composition at seven each night. His promises were like a woman’s – made to be broken. He never paid me so much as one penny. But he was such a nice chap! I always forgave him.

Previous to this, I had learned the arts of paper-ruling and bookbinding, with Mr. W. Rose, of Leigh Street, Adelaide. We did all kinds of ruling, from faint-lined on both sides of the paper, to complicated tabular work.

We also made heavy Ledgers with spring backs, and bound books of every description.

Train to Kapunda.

Then a big Cobb & Co.’s coach on leather hinges to Burra Burra.

These lumbering but useful and interesting vehicles were named after a Mr Cobb, a Californian, who was attracted to the Victorian diggings in 1850, and started coaching to and from the goldfields.

He imported Yankee coaches of the lightest and strongest makes, and smart Yankee drivers with them. As many as eight horses were sometimes driven in a team.

We never used more than six – mostly four, occasionally five. The leather ‘hinges’ were just loops in place of steel springs, the body of the coach swinging on four loops.

Eight miles an hour, including stoppages, was the contract rate of travel on all main routes, and seven on outside tracks like the Great Eastern Plains.

On this, my first, journey to the Burra, we met immense teams of mules carting copper ore from the Burra Burra Mine. The tracks – there were no roads – were awfully cut up. All dust!

Our food was well shaken down for us. No extra charge! Fare for the fifty miles, One Pound stg.

Passed through all the old townships – Hamilton, Marrabel, Black Springs, Sod Hut, Apoinga, &c.

Near Black Springs I was much interested in viewing the dry bed of an immense lagoon to the eastward, lying alongside a range. And in the distance, to the N.W., another large live lagoon was visible. This, I think, was Porter’s Lagoon, which lies east of Farrell’s Flat, and at which, many years later, I have often been duck-shooting by moonlight.

One other dry lagoon-bed was also visible. I thought these sights characteristic of Australia, and they had a fascinating charm for me as a youth.

We arrived at Kooringa at 6 p.m., smothered in dust. (Kooringa today is known as Burra South and is the main part of the town of Burra.) Got an excellent bed at the Burra Hotel (Above: Lamb’s) – now the Burra Hospital. That evening, before turning in, we three explored the whole of the Burra, which was then a very brisk and lively place.

The big mine was working at its full capacity, with about twelve hundred hands. We inspected the surface workings.

A ponderous Cornish pump was throwing water in a great stream from a shaft at the head of the gully A rope at the pumping-house was as thick as the calf of a man’s leg. It was three great cables twisted into one. It was a marvel to us!

The arms of the pump were immense, and must have weighed many tons. The hotel we were staying at was the very first building, from the Kapunda track, in the Main Street of Kooringa. It did a roaring trade.

TO MOUNT BRYAN March 31, 1864.

Our first day’s tramp in the Bush was from Burra Burra to Mount Bryan sheep station – fifteen miles. Not one of the nine of us knew the way to Paratoo, our terminal destination. An old man amongst us thought he did!

We had passed our last fence the day before – at Black Springs. There was none between us and the ocean on the shores of the far-distant Northern Territory. The old man was to be our guide!

In starting, we had one mile to go to get through the townships of Kooringa, Redruth, and Aberdeen and the mine property.

The Burra Creek was already denuded of its gum trees. Miners were working in its bed. The lower banks and bed were green, and the running water was green also. The latter, being impregnated with carbonate of copper, deposited some of its contents upon whatever it came in contact with.

The immense Cornish pump on the hill at the head of the gully continued forcing up a great volume of water at each stroke. This ran down flumes, and turned a big waterwheel near the creek about half a mile distant, and kept the creek supplied with the green liquid. It would have been sudden death to drink it! But it was good enough for the Cousin Jacks to wash the ore with.

I was much struck by the wonderful contortions of the stratified hard limestone rock showing in cuttings. There had been a great crushing of the strata there at some early geological period.

In the banks of the creek were many dugouts, in which the miners lived – modern troglodytes! Getting out of the townships – there was Copperhouse on the left hand – we journeyed up the flat five miles to Hallett’s Head Station, where there was a well of good water.

The weather was very hot. The dry grass was high, and thick enough to completely hide the soil from view. It was the usual silver grass. To see the Mount Bryan Flat a year or two later, one would never dream that it was once covered luxuriantly with the tall native grass.

On the left was a range fifteen miles long, on the right a jumble of ranges and hills. Beyond all, on the right had, or east, were the great Murray Flats, and the scrub where Mr Bryan perished in the Thirties, whilst, with others, endeavouring to return to the Nor’-West Bend.

With us, there was no road – only a track. It branched into two at six miles. One of these went northward or thereabouts, while the other forked to the right. We took the latter.

The scenery was delightful. Before us lay The Razorback – now named Mount Razorback – 2534 feet above the sea, and eight hundred feet above the plain. We at first mistook it – as many people still do – for Mount Bryan, which, however, is ten miles further back, quite out of sight, and is much higher – or three thousand and sixty-five feet. It is on the outer edge of the great great range, and overlooks the immense plains to the eastward.

The nine of us wended our way across the interesting plain, with its little hills and undulations – the big mountains always before us. Although the day’s tramp was a matter of only fifteen miles, yet is was late in the day when we sighted Mount Bryan Head Station, situated on the eastern point of the range.

I, being the youngest member of the party by many years, was in the van, leading the way, and arrived at the kitchen first. The kitchen is the most important place on earth to weary, thirsty, men who are on the ‘wallaby track’.

I calmly walked into the pine-slab, thatch-roofed edifice, followed by Martin – a one-handed man, with an iron crook in place of the lost hand. The cook looked at us sternly – It was a man of course, for there are no women cooks in the Bush – although I came across one later on – ‘the exception that proved the rule.’ The lawyer’s clerk and the parson’s son then hove in sight. The cook turned pale!

Others came in, like lame ducks, until the only one missing was our ‘guide’! The cook, by this time half-stunned, went to the door, arched a hand over his eyes to shade them from the dazzling rays of the setting sun, looked down the track long and earnestly to see how many more were on their way to invade his sanctum. The old man alone was in sight.

The cook waited till he came in, then continued to gaze down the track. After giving out an immense sigh, whether of relief or despair no one ever knew, he returned to his camp-oven and fireplace. A blank look was upon his countenance, but he faced the music like a man.

Our unceremonious interruption caused him a lot of extra work in the shape of cooking, without any extra pay. And none of us had the sense to make the poor fellow a donation of a silver coin. Such an action was never heard of in the Bush!

Sitting at the foot of an immensely –– long table of adzed slabs, when the evening meal was in progress the Man-with-the-Iron-Crook noticed that the ‘sugar’ near him was black, while at my end, near the cook, it was beautifully white.

He immediately called out loudly – (he was an assertive Irishman) – for the white sugar at the head of the table. He didn’t believe in the vile cook having all the luxuries to himself. Oh, no!

The cook, with a sardonic grin, motioned me to pass it along; which I did, also with a quiet smile to myself. Putting a liberal supply of this ‘luxury’ into his pannican, the Man-with-the-Iron-Crook stirred it well and prepared to indulge himself in a glorious drink.

Placing it to his lips, and leaning back with shut eyes the more to enjoy the nectar,

he ___! ___! ___! ___! ___! ___ became a spluttering and spitting volcano of oaths and tea! – to the intense delight of those in the know! Even the cook became more cheerful.

The ‘white sugar’ was course lake salt! So the man’s tea could hardly have been sweet enough for him. Perhaps that was why he spat it out!

This Martin, by the way, was a relative of a man named Malachi Martin who had some connection with an awful murder which had recently been committed – I think in the South-East – the body of the victim having been concealed in a wombat hole. The murderer was hanged.

I cannot remember the particulars, as I was too young; but I know the affair caused a great sensation. Whether Malachi Martin was the principal in the murder I cannot say, but I am under the impression that he was.

Read more: Malachi Martin (murderer)

That night at Mount Bryan station proved cold. We slept in wooden bunks, each upon a single sheepskin, well woolled, and black with mixed yolk and dirt. One blanket did not keep out the cold, and in the morning I had to walk about in my sleeping-shape until the muscles thawed out. Mount Bryan is ever a cold place at night, except in the summer time – the Head Station being about two thousand feet above the sea.

MOUNT BRYAN TO WOORKOONGARIE. April 1, 1864.

Having breakfasted upon damper and mutton – the same fare that we had partaken of the previous evening – we made an early start. Station hands were no sluggards. At six a.m. they had breakfasted and were at their work, whatever that occupation may have been.

We started upon our travels across country for a station named Woorkoongarie – called by tramps ‘Walk-Hungry’ station, because the owner – one Chewings – invariably sent hungry men hungry away.

We had to cross a spur of the Razorback, and found it steep and rough. For many miles we traversed hills and gullies, passing one hut. Thirty five years later I came upon the very same hut, in ruins, and recognised it at once.

[On this latter occasion I had a camera on my back, and was returning from a tramp alone which I had undertaken to the top of Mount Bryan in search of views.

The ranges to the north looked big and gloomy to me in this year of one thousand eight hundred and sixty four. Yet it was over them that I walked with my camera – a whole-plate – nearly two score years afterwards, after an eventful life of hard work, trouble, happiness, and adventure.]

[That journey from Mount Bryan Flat to the top of Mount Bryan took me twelve hours – seven hours to find the Mount, which I scaled at three p.m., and five to get back. Weight of camera and appurtenances thirty-seven and a half pounds avoirdupois; distance travelled, thirty miles.]

On this, my first, trip into the Bush, the ranges northward appeared so gloomy and forbidding, that had I been told I should make such a journey alone I should not have believed it. Indeed, had I attempted the task on this my initial trip into the Bush, I should have been hopelessly lost by Nightfall.

Toiling along on that first of April, 1864, we found the dry grass plentiful, the scenery mountainous on our right, with the plain and some hills on our left.

After crossing the southern spur of the Razorback, we traversed undulating country, and skirted Wildongoleech – sometimes called Willogoleech – where the township of Hallett now stands, halting for a rest some miles south of where gold was afterwards found – viz., Ulooloo.

The dry grass at our resting-place was thin and patchy. While reclining on the ground, the Man-with-the-Iron-Crook took it into his silly head to put a lighted match to it! The match was one of the olden kind that posts and rails were made of. The heads when placed on the nipple of a pistol and the trigger pulled went off with a bang! We boys made crackers of them by fixing the heads in the hinges of our pocket-knives and opening the blades.

The flames crackled! and in the bright sunlight were hardly visible. But they travelled! I was on my feet in an instant, and had the fire stamped out before the wind could carry it any distance. It was a close shave!

Resuming our journey, by and by we left the grass land behind and encountered barren soil, with scattered quartz and ironstone on the surface. Trees began to appear, and we soon found ourselves in the Ulooloo Creek.

Since then the place has been worked as a goldfield. The heaviest nugget obtained weighed twelve ounces.

Then we entered a thick mallee scrub, and signs of the eastern desert began to show. In this scrub I saw a dead animal hanging by a foot from the fork of a tree. As the shades of evening were falling, we arrived at our destination – namely, the sheep station bearing the euphonious name of Woorkoongarie. And now for an illustration of why travellers nicknamed it ‘Walk-Hungry’ Station!

We nine Muses – enough to give any station-owner the blues! – were very hungry. True, we had travelled only fifteen miles, without food or water, but the road had been hilly, and we were ravenous after our thirst had been quenched, for the water here was good.

Taking possession of a large empty men’s hut on the station was our first act. The night was cold, and there being plenty of wood, we made a big fire in the wide chimney-place. The station bell rang for tea!

With visions of damper and mutton, and a pannikin of black tea sweetened with black sugar before us, we nine made for the kitchen en masse.

But ‘there’s many a slip’, &c. We had reckoned without our host – the aforesaid Chewings! He barred the way! He refused to let us have anything to eat on any terms! So we all marched back to the hut; hunger knawing at our vitals, as some poet has said – or was it a novelist? But we had not done we with this Chewings! In solemn conclave assembled, we had a discussion, deputationised the owner, and requested him to sell us some flour – just flour, nothing more. He refused point-blank! saying he would neither give nor sell.

Back we marched again. And, feeling very stern, we decided to take the matter into our own hands. We accordingly waited upon him once more, and quietly but determinedly informed him that as he had declined to see us food, we would take it by force! That brought him to his senses. He immediately went to the Store and presented us with a good-sized dishful of flour – no meal, or tea, or sugar, or salt.

We were supremely happy, however, for we now had some flour and plenty of good water. Ah! how we appreciate good water in the Australian Bush! We were soon at work making unleavened bread – in other words, ‘Johnnies-on-the-Coals.’ Bushmen call them by another name; but I need not put it down here – it is real Australian! (a type of damper cooked in hot coals, often in a camp oven or over a campfire. It's a simple, traditional Australian bread, sometimes referred to as "bush bread" or "campfire damper")

We were eating those ‘Johnnies’ long before they were cooked. Hunger was the sauce! A pinch of salt would have improved their flavour certainly; but we were too pleased with our good luck to carp at the absence of such a trifle. We cooked the ‘Johnnies’ on the red embers, and ate till they were gone. And we were still hungry! For what is a tin dishful of flour amongst nine men? – although perhaps I should say eight men and a boy.

We washed our meal down with cold water. Then we all turned in to a bunk apiece, and were thankful for that, with a sheepskin under us for a couch. The hut was built of the usual pine slabs or pine trees in the rough, with the bark on, and pug in the instercices between each slab or tree.

WOORKOONGARIE TO PANDAPPA. April 2, 1864

On this day we had a long journey to accomplish – a distance of thirty miles. The worst of it was, no one knew the way. There was no defined track. The day turned out frightfully hot!

On the morning of this memorable day I saw a dog get the severest thrashing he had ever had in his canine life. He had committed some offence, and a brother-in-law of the aforesaid Chewings – Mr Hiles by name, I believe – suddenly collared the dog by the scruff of the neck, and with a stick in the other hand thrashed him with a vim and a vigor one sees about once in a lifetime.

The dog was so taken by surprise that he actually screamed, yelled, and howled with terror all at the same time. But the man was furious. His right arm went up and down mercilessly like a flail – whilst the shrieks and the uproar were something to remember!

At last the executioner tired, and let the dog go, with a parting kick! The way that canine then travelled was wonderful to see!

With his tail between his legs, and his nose between his paws, he, without so much as looking back went like the very wind – over a scrubby range, straight away from the station, and for aught I know may be going yet.

I think it probable, however, that, his speed being so great, he flew at a tangent right off the face of this planet and turned into a comet in the constellation of Canis Major. Comets have tails. That dog had a tail, and it would naturally get more elongated the swifter it went. He is not Halley’s comet, but he may be one of the other less notable ones.

This same brother-in-law had a kind heart after all! Upon seeing us start on our rather hazardous journey, sans breakfast, he immediately went to his own hut, and, out of his own rations, presented us with a forequarter of mutton already cooked, apologising to us at the same time for the scurvy treatment we had received, and which he was powerless to prevent. And here we find two men of character! We thanked him heartily, and asked him to try and put us on the right direction for Pandappa. This he did to the best of his ability.

A track went out through a valley and over undulations for ten miles, and then ceased, leaving us twenty miles to cover without a track or distinctive landmarks. We had a half-gallon tin canteen with us. It was empty before the ten miles was accomplished. The day was a roaster, and the half-boiling liquid did us no good. We ate most of the meat at starting. It fortunately contained no salt to make us thirsty.

We had now got into the true desert. Saltbush-covered hills were around us, and very soon all trees had disappeared. The sole vegetation was the saltbush, which stood about a foot and a half high. It was splendid feed for sheep, and the bushes were well-leaved and in good condition. The leaves were broad and of a sage-bush color.

We were in luck that day! Coming to the end of the track at ten miles, there was nothing to point out our route. An immense plain, studded with hills, lay in front of us, on our right and left saltbush covered hills. In the far distance, hills, all with the same vegetation. Not a tree to be seen.

Not knowing what to do, we waited a while. Our ‘guide’ was a failure.

Presently we saw a horseman approaching from the N.E.

He proved to be Peter Waite, the then manager and part-owner of Paratoo and Pandappa. At anyrate he was manager at One Thousand Pounds a year. I think his interest in the runs at that time was small. Mr Thomas Elder was the real owner.

Peter was cantering his horse. Upon nearing us he drew rein for a moment, looked us over with a supercilious eye – a la the Kaiser. He had been expecting us, as the lambing season was on.

Peter Waite acquired a city estate at Urrbrae in 1874 but he lived on Paratoo station most of the time until 1891 when his new Urrbrae House was completed.

We were told afterwards that he had a great dislike for men who were engaged in the Adelaide office. Upon our asking him to point out the way to Pandappa, – there being no visible trail, and we were twenty miles from our destination, without water or food, and a blazing hot day before us – he, without giving directions of any kind, put spurs to his horse, and curtly shouted as he disappeared: ‘Follow my horse’s tracks!’

He was a Scotchman, young, tall, handsome, and, as I have said, supercilious. I reckoned him then to be about twenty-seven years of age – or twelve years older than myself.

The ground was dry and hard, and horses’ hoofs made hardly any mark. However, boy-like, I prided myself on my tracking abilities, and here was a chance for me! My method was, not to look down at my feet, but fifty or one hundred yards ahead, when any fresh disturbance of the soil or plants could generally be noticed.

So I forged ahead, and kept the lead all day. After a time, our feet became horribly blistered, but we kept on. It was torture for me to put mine on the hot, bare, ground. For no grass grows between the saltbush. I had to keep on, however, and grin and bear it.

Sitting down on the ground, I took off my boots and socks, and found my feet a mass of blisters from heel to toe, some as large as a half-crown piece. In fact, the soles of my feet were practically flayed. I cut the blisters open with a penknife. When the hot water ran out, the pain was most acute, the sensation being like burning by fire.

I did not know then that to get the fluid out of water-blisters painlessly the proper method to adopt is to run a darning needle full of worsted through the blister, drawing the worsted half through, cut the needle loose, and leave an inch of worsted sticking out at each end.

The water then soaks through the ends, and, the air being excluded, the scalding or burning sensation is left out of the programme. This plan I invariably adopted afterwards.

The weather was so hot, we were absolutely dried up. No moisture remained in our mouths. Going thus another fifteen miles through the saltbush, we came to a very deep well – how deep I cannot say, but I should think about one hundred and twenty feet. It had just been sunk. There was no windlass, whim, or anything by which we could raise water.

At last we found an old, dilapidated billy. Tying together some short lengths of yarn lying about I obtained length enough to haul up a few ounces of water. It was undrinkable! The twang was awful!

During the last fifteen miles I reckoned we had been travelling nearly due east – or it may have been N.E. We nine Misereres now held counsel together to see whether we should camp there for the night, or go on and try to find the station.

I cut the matter short by picking up the horse’s tracks again, when my two mates followed me. The others were for staying. But the Man-with-the-Iron-Crook followed us three. Then the rest came on, one after the other, Indian fashion.

Night was approaching. The tracks could not be followed much longer. We were parched, footsore, and weary. Yet, being young, I was lively enough. So I put on the pace and forged ahead on my own. The others could follow if they chose!

Looking back, I found them all on my trail. There is not much more to add. We had now got into hills and ranges. After taking many turnings and twistings amongst the stony hills, just at dusk I got over a low range, and there on the other side lay Pandappa Head Station! (The station homesteads are mainly ruins and deserted but this is still good sheep country.)

Pandappa Head Station is a historic location, formerly a pastoral lease near Terowie in South Australia. It was once owned by Peter Waite, who later became a prominent figure in South Australia. The property was known for its innovations, including a tiled roof, electric light, and refrigeration. Today, the area is likely part of the larger Pandurra Station.

Choked with thirst, and forgetting our blisters, we three pioneers ran down the side of the stony range in amongst the scattered huts, looking for the men’s Kitchen to get a drink. The-Man-with-the-Iron-Crook, who had caught up with us, tumbled heels-over-head going down the range, but was not much hurt.

I being in the lead, got in first, seized a pannikin, filled it with brilliant-looking water standing there in a bucket, and swallowed the contents! Brilliant water, like brilliant women, should be looked upon with caution – and be tasted a little bit at a time, until you are sure of their dispositions.

The pannican then went around, and my turn came again. This time the water did not taste so nice! Again the pannican made the circle. Then I found that this brilliant-looking water was most decidedly brackish! And thereafter I was unable to quench my thirst with it. That awful North-Eastern water! It was horrible!

The lame ducks came straggling in one after another, and they all made for the water-bucket. Few of them noticed the brackishness at first, but the beverage palled upon them later. Then came the evening meal of mutton, damper, and tea. We slept again on the usual sheepskin at night.

PANDAPPA TO PARATOO. A COACH JOURNEY. April 3, 1864

On the previous evening the mailcoach and four arrived, and stayed at Pandappa the night. It was a fortnightly service on this route. That morning – Sunday – I had orders to get aboard and proceed by it to Paratoo, as lamb-minders were urgently needed.

Thus I was saved a further walk of thirty miles, which most of the others had to undertake. Some were to stay at Pandappa and work there.

To me it was a glorious journey on the mail-coach – over the saltbush plains surrounded by hills – or, shall I say, thickly dotted with hills? It was really both. The scene was constantly changing.

Our first stage was to Burranunyaa – incorrectly spelt Burranunyah. Blackfellows’ names almost invariably end with a vowel. This stage was fifteen miles.

Burranunyaa Well contained the best well water I had tasted up to then and since in the North-East. The well was alongside a low range. From here to Martin’s Well was five miles. This well was one hundred and twenty feet deep, the water undrinkable except by sheep. The unfortunate sheep had to drink it or perish. The well was sunk in solid rock, and had no timbering except near the top. Words spoken in a low voice at the bottom could be heard distinctly at the top.

From Martin’s Well to Paratoo Head Station was twelve miles. This we accomplished before midday. Another change of horses was made at Paratoo; but that did not interest me, as I had reached my destination.

Those of the Noble eight who tramped it to Paratoo stayed one night at Burranunyaa, At the camp The-Man-with-the-IronCrook managed to get his blanket burnt. The night was cold, and he got too near the fire.

I saw him once more after his arrival at Paratoo. They made two stages of the thirty-two mile journey from Pandappa to Paratoo. Of my two mates, I afterwards saw the lawyers’s clerk and the parson’s son working in a trench at Paratoo under the supervision of Peter Waite. He kept his eye on them from a convenient hillside!

I wonder what value they were as laborers! Paratoo Head Station was situated in a very pleasant position on the Paratoo Creek in a gap in the long, low, stony range. The gap was named Paratoo Gap. The view around was extensive, the gap being wide and open.

July 16th 1864. The time had now arrived for me to start afresh upon my travels. Having been paid off by Peter Waite himself, at the rate of fifteen shillings a week, I bid farewell to Paratoo Head Station.

My sixteenth birthday was on June 14, 1864.

Fiancee Marianne Clode

Marianne Clode – then about sixteen years of age – the same age as myself, plus nine days – seemed to understand each other in a wistful kind of way.

We were well acquainted in North Adelaide. We went to Sunday School together. Her brothers, Tom and Alf, were great chums with me, and I was often at their house.

No words of love passed between us, as she was already engaged to a young man three years her senior – therefore nineteen. Being himself very prim and prudish, he at last came to the conclusion that she would never adorn the select society to which he belonged, and so decided to give her up.

And she a born lady, with a heart of gold, and rich family connections.! Her uncle had been the Mayor of Queen Victoria’s town of Windsor, where Windsor Castle is situated. And Marianne was born there – that is at Frogmore. Her people had big business connections in that town.

She was handsome and true. Well educated herself, she could play the piano in first-class style. She sang in her rich voice, and was in Mr Unwin’s choir at Walkerville. The happy hours we used to have at the piano when I was in town! She and her mother, and also her sister Ada, used to play their grand duets for my special benefit. Those were happy times! But very short. I was away so much.

It was at this juncture that I received a letter, full of tears, from dear Marianne. In it she told me of her so-called lover giving her up. She poured out her heart to me, and then I knew that she had loved me all the time.

I replied immediately, and gave her all the sympathy she could desire. I was happier now in one way; but a desolation seized my heart. How was I to earn sufficient to give her a good and happy home! I could not solve the problem just then, but did so in another five years, after many sad and long partings – one extending to over two and a half years in a faraway land.

She was true and faithful to me all that long time, refusing many tempting offers of marriage, for she had grown up to be one of the finest and most handsome young women to be found in Adelaide.

She and her mother kept a school, and had many music pupils. Her mother taught French also, which was a fashion with educated people then.

After this we wrote regularly to each other every mail. The mails to the North-East were fortnightly, as I have said. And that was the nice, easy, and natural way in which she took possession of me! - - -

It was now the end of 1864, and I was sixteen and a half years of age, nearly. While at Glenelg I thought of nothing but Marianne.

One night, after darkness had set in, I strode out and walked all the way to Tynte street, North Adelaide – a distance of eight miles – in reality to have an hour with Marianne; but my excuse was I had forgotten my concertina!

I knocked at the door. Dear Marianne opened it. She had beautiful eyes. The light shone in them as she saw me, and her lovely face was diffused with blushes. She, usually so staid, called out excitedly: ‘Mother, Henry’s come! Henry’s come!’

From that time onward we were lovers, and, single and married, remained so for forty-two years – from 1864 to 1906, that fatal year in which I lost her for ever!

That night I walked back to Glenelg, playing the concertina the whole way. It was an English concertina, worth Six Pounds sterling, and one of the sweetest-toned instruments I had ever handled.

In February 1869, aged 21, I established the Northern Argus newspaper at Clare.

On New Year’s Day in 1870, I married Marianne Clode at Christ Church, North Adelaide.

Marianne (Clode) Tilbrook (1848 - 1906)

Born 5 Jun 1848 in Windsor, Berkshire, England.

Died 15 Dec 1906 at age 58 in Clare, South Australia, Australia

Above: First Edition of the Northern Argus

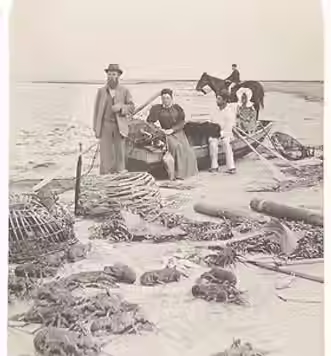

Spoils of the Ocean 1898 Pelican Point

Henry Hammond Tilbrook's (1848-1937) youthful experiences in the north of South Australia 1864-5, with photographs taken in later life.

Bush Life celebrates the youthful diaries of South Australian pioneering photographer Henry Hammond Tilbrook (1848-1937), recording his adventures in South Australia's mid north in 1864 and 1865.

Henry returned to the area 30 years later as an established photographer.

In 1937, in his eighties, he rewrote his youthful diaries as journals for posterity, and called them Reminiscences and Memoranda.

The book features a selection of his remarkable images of the mid north including Burra, Mount Bryan, the Flinders Ranges, and beyond.

Kym Tilbrook, the great-great-grandson of Henry Hammond Tilbrook, launched the book on Wednesday, 21 September 2022

Henry went on a number of photographic excursions with Fred Lester and others, but usually left them and went off alone, or solus as he called it, carrying his heavy camera gear in search of suitable subjects. Photographic excursions he mentions in his writings and included here were:

1894 - The Flinders Ranges

1898 - To Mount Gambier and district

1899 - To the top of Mount Bryan, north of Burra.

1900 - Back to the South East

1905 - Mount Gambier and Portland, Victoria.