The Grey River Argus 1866

I mustered up courage to apply for a billet as compositor at the Grey River Argus office. I did so, and was taken on at once. The wages were Three Pounds Ten Shillings – (£3. 10. 0) – per week, as I had not served my full apprenticeship of five years.

The proprietors allowed the two and a half years I had been in the Register office to go towards the five years required to complete the indentures. Then I wondered if I was worthy of the situation!

A new office of galvanized iron in Boundary Street on the upper or Mawhera block of the town was nearing completion. It would be ready by the following Monday. In the meantime I was starving. So I went to my erstwhile mate – Harry H – at Moorhouse’s hotel. I had spent my last bit of money on him.

So I asked him for the loan of sufficient to keep me going till I got my first wages. He was generous! First he gave me a drink of something warm. Then he handed me the magnificent sum of – half a crown! That would buy two pounds of steak and half a quartern loaf.

It would be a fortnight before I earned anything. So there I was! Too proud to beg; too high-principled to steal! I had a good mind to throw the half-crown at him. But I controlled my anger, and pocketed the money.

I went to work on a Monday in the new office in Boundary Street, but had another week to go before getting any money. I hadn’t a bit of food left, and I could not fish while working. Our hours were from 8 a.m. to 6 p.m; but on the three publishing nights we kept at it till one, two, or three o’clock in the morning, and returned to work at eight a.m. as usual, after a few hours’ sleep. We did not receive overtime pay. Nor did we expect it.

I had already starved for three days and three nights, when a stranger to me whom I had met, and whose tent was pitched near mine – he was a painter by trade – invited me to have tea with him one night. Glory, hallelujah! Having starved for seventy-two hours, working hard in the printing office all the time, I accepted with alacrity, and went.

When I arrived at his tent, empty-handed, he looked at me in astonishment; and asked why I had not brought my tucker with me!! It was I who was amazed then! The idea! Asking a fellow to tea and expecting him to bring his food with him! I was taken aback. That was the first time I had had such a curious invitation.

But everything was dear then, and giving a man even one feed meant money. At last I had very reluctantly to confess that I hadn’t any tucker to bring – nor money wherewith to buy it. He thereupon invited me to dine with him till Saturday, when, out of my first Three Pounds Ten Shillings I paid him liberally for his kindness.

I was now in clover! My experience of starvation was this: –

-

On the first day and night I was ravenously hungry;

-

on the second day, even more so;

-

on the third day, very weak and weary indeed.

-

On the second day, I found a crust of bread weighing about one ounce. I ate that, and was astonished to find what strength it gave me for an hour or two!

Strange to say, now that I was in affluence, my ex-mate Harry H., got out of his job, and came whining to me for help. Being only too glad to succor him, I fed him gratis, and allowed him to share my tent again without charge. Not only that, but after much trouble I got him a billet in the Grey River Argus office as ‘Printer’s Devil’ – or roller boy – at Three Pounds per week. By the way, he was a ‘boy’ of about thirty-two years. I was a compositor – both ‘news’ and ‘jobbing’.

The question now was where to find a new spot to pitch our tent. I chose the edge of the scrub, some distance in where the trees were a bit thinned, and the furthest out from civilization. The ground was low and slushy. But there was no such thing as a dry, clean, spot anywhere. I set to work and cut a lot of timber to be used as a foundation platform for the tent.

There was no knowing how high the floods arose in the winter time. The site I chose was half a mile back from the river Grey. Harry H. laughed at me for going to the trouble of felling timber and building a high oblong base for our calico dwelling. Why not fix the tent in the slush like other people?

Why not, indeed? So easy! Following the lazy line of least resistance! However, I differed. I was always original, and never exactly like other people. And it was well I had my own way! Often afterwards the floods arose to within six inches of the top of my platform, but left the floor of the tent dry.

I built up the logs Canadian backwoods fashion, horizontally – not Australian style (vertically). On top of all I made a corduroy platform of round logs, running across from side to side. The logs were six inches thick – the platform about two feet six inches high. I then nailed some canvas on the floor of the platform. That was my bedstead and bed. I loved hard beds then. And that particular bed was about as hard as a man could wish for! I slept [on] the timbers.

I had learned from experience that lying on logs placed longitudinally stopped the circulation of the blood very seriously, and sent the legs to sleep badly. That was all the mattress I had, and I found it perfection.

Upon this substantial foundation I erected the tent securely, obtained a ‘fly’, and fixed that over all, thus making the tent fairly rainproof. In the muddy ground facing the entrance, or flap of the tent I planted four posts and nailed tin around them. That was the fireplace and chimney. This I connected with the tent by a light roof of brushwood. Thus we were made very cosy.

I was now fully established at the Grey River Argus office. It appears I gave the proprietors every satisfaction. There were then four of them – Messrs. Moore, Jack Arnott, Jimmy Kerr, and Jack Keogh – all good fellows. They were all compositors.

I was very doubtful of my ability at first, being so young. I was absolutely the junior in the office. But I worked as deftly as the other compositors. My ‘proofs’ were always ‘clean’ – that is, they showed few errors.

Some compositors’ proofs are quite black with the correction marks at each side. As before mentioned, the Grey River Argus was a tri-weekly, four pp. double demy, seven cols. to the p. twenty-inch cols, thirteen ems Pica wide.

Every composition day I ‘set up’ by noon one column and a quarter of ‘thin’ bourgeois, solid; or the same of ‘thin’ brevier, leaded with eight-to-pica leads. None of the others ever composed more than three-quarters of a column in that time. There was too much brandy about, and the men often stopped to have a ‘nip’.

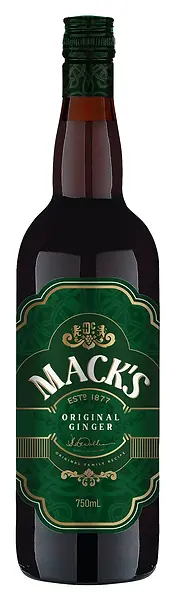

I was practically a teetotaller, drinking ginger wine only when I was forced for decency’s sake to join in a ‘shout’ – the said 'shouting' being a thing I ever abominated.

Compositors of those days were, many of them, big drinkers; and some of them were gamblers also. Instead of paying for a drink when they wanted one, they tried to make the ‘other fellow’ pay for it. In other words they ‘jeffed’ for the drinks.

Taking nine em quads out of the type case, they shook them up in the hollow of their cupped hands and threw them scattering fashion on to the ‘stone’ – (a stone is an iron table). They did this three times each. Each ‘em quad’ had a nick on one side only. The man who threw the lowest number of nicks had to pay for the drinks. (an em quad is a square space in a font, with its width and height equal to the current font size (the width of an "m").

It would be possible to throw nine nicks at one throw; but I don’t suppose that has ever been done in the history of printing. For one long period, Jack Keogh was let in for paying for all the drinks. He was a good-natured Irishman. He and the other three proprietors worked in the composing room as compositors.

Being thus victimised every time, Jack, in desperation, said to me one day. ‘Come and jeff for me, Harry, and break my bad luck.’ So I jeffed for him and got him out of his trouble, for he did not have to pay for drinks for a long time after that – but one of the others had to!

In the Grey River Argus office were: –

-

W. H. Harrison, editor;

-

Mr. Blackham, clerk, collector and canvasser;

-

the four proprietors mentioned, all ‘news’ compositors;

-

H.H. Tilbrook, news and jobbing compositor, and afterwards overseer;

-

my ex-mate, Harry H., roller boy and Printers Devil;

-

Bill Riley, pressman;

-

one other compositor, and sometimes two. The personnel of the latter varied, but there were nearly always two other ‘comps’. That would be seven compositors in all. Two of the extra ones were named Kirkbright and Stark respectively.

We were a happy family, all taking an interest in the newspaper. When the canvasser obtained a lot of ‘ads’, shares were up, according to the phraseology of the case-room, and we were all pleased. At first the men were getting Seven Pounds per week, but this was afterwards reduced to Six Pounds.

Then came other reductions. Jack Arnott was, by common consent of the proprietors, the real manager. He was tall and thin – a Scotchman, of course.

One day a mate of his stuck a long, lean, lucifer-match upright in the centre of his lowercase ‘e’ box. When he came in and saw it, he thought the joke had gone too far, and words ensued.

I did not remain long on a salary of Three Pounds Ten. One Saturday, upon being paid, I took Mr. Jack Arnott into the front office and quietly asked him for a rise. I intended asking for an additional ten shillings. To my surprise, Jack Arnott, as soon as I had made my request, said, quite cheerfully, ‘Why, yes, Harry, we intended giving you a rise, and from to-day you will receive Four Pound Ten Shillings per week.’

My next rise, without asking for any, was to Six Pounds per week. That was when they made me inside manager of the office. The men never resented the junior of the office being made manager. When I first went on, I was sensitive to my own shortcomings So I worked as hard as I could, and usually had my case [of type] pretty well empty by dinner time – it is called lunch time now.

One day, ‘Kirk’, a fussy compositor who thought he was in the good graces of the proprietors and thought no ‘small beer’ of himself, said to me, ‘My word, Harry, you are a slogger!’ I was young then, and didn’t know whether he meant it as a compliment or an insult. So I lay low until I found out what the word meant. I found it was a compliment. He meant a rapid compositor, which I found I was.

‘Kirk’ is referred to in a letter I received from poor old Jack R–, and which I shall quote further on. That was after I had left the office and returned to Australia.

A most amusing incident happened once in the composing-room of the Grey River Argus. A pert little fellow came down from Auckland and asked for a job. He was taken on as a news compositor – one of the easiest billets, to a competent man in a newspaper office.

He left Auckland because of the Maori War still going on in the North Island. He had to go into camp every now and again; and even while in the tents, bullets from the Hawkers whistled through the air and pierced the tents. So he whistled to himself and went south.

In my diary is this entry: –

‘These men were called militiamen, and were taken from the population of the North Island. This man was taken from his ‘frame’ in an Auckland newspaper office and had to fight against his will. He said the Maoris sent bullets through the British tents at every opportunity.

If a guerrilla system of fighting had been adopted by the British, the Maoris would have been beaten in a few months.

But the Redcoats – wearing a bright scarlet coat, mind! – were marched into the forests in close formation, whilst the Maoris lay in ambush for them, and were slaughtered wholesale.

Sir George Grey was a great muddler. He befriended the Maoris, and was the cause of the war lasting so long."

To resume: –

When the cheeky little compositor came into the composing-room of the Grey River Argus office, he perked himself up, and loudly acclaimed to all and sundry that he had always been the ‘whip’ hand in every office in which he had worked.

I made a mental vow to myself that he would not be the ‘whip’ hand in the composing-room of the Grey River Argus. The others said nothing, but smiled. When he went out, I heard Jimmy Kerr, one of the Scotch proprietors, say. ‘I’ll back Harry against him!’ ‘Harry’ was myself. I smelt a rat!

Nothing was said to me, however. But on the morrow, the perky little comp. was given a frame alongside mine. I knew the object well enough, and I was on my mettle. I had by this time adopted the most rapid method possible of picking up type.

My left hand, with the ‘stick’ in it, followed the right hand close up, so that my right hand, with a type between thumb and forefinger, had not far to travel. Some compositors let the right hand do all the travelling. They are thus very slow.

With practice, I could set up a big stickful of solid bourgois every quarter of an hour; the same of brevier leaded with eight-to-pica leads; and six sticks of solid long primer in an hour.

The tug of war began without a word. We started together. Everybody looked our way. I had one line finished and spaced out when he had only half-a-line set.

I gained on him rapidly. I had smaller type, too – solid brevier, very ‘lean’ – while he had bourgeois, or a size larger, and much ‘fatter’. This was a big handicap against me.

My ‘stick’ was about two inches deep – his one and three quarter inches. In fifteen minutes I had my composing ‘stick’ full, and the type ‘lifted’ on to the brass ‘galley’. All hands grinned!

The little fellow, in tremendous disgust, clapped his ‘stick’ – only half full! – on to his ‘frame’, and went out to the back. A roar arose from all hands! Jimmy Kerr was especially pleased, for in his quiet way he had taken a liking to me.

When that young man of thirty years or thereabouts, who had been the ‘whip hand’ in every office he had entered, came back to his ‘frame’, he was in a subdued state of mind. He was not the ‘whip hand’ in the Grey River Argus office at any-rate! As a matter of fact, he was a very ordinary hand.

He had rapid movements; but that did not denote speed by any means. I made it a rule never to miss a type. When my finger and thumb darted to pick it up, they picked it up without any false movements. Some comps have so many false movements, that they become absolutely slow, setting no more than two thousand type per hour – or even only one thousand to fifteen hundred.

My duties in the office were managerial as well as practical work. I had to design the posters and the various other printing in the jobbing department. But the newspaper always came first. As we issued tri-weekly, at least three days a week were taken up in composition for the paper. And the ‘dis’ had to go in and jobbing work done on the day of issue.

We started work at 8 a.m. – it was then dark in the winter time – and seldom knocked off till two o’clock next morning. There was too much stopping to ‘jeff’ for drinks to please me. But for that, we might have finished by midnight.

The ‘comps’, when all ‘copy’ was set, and ‘proofs’ were corrected, could go home to roost. I myself, being overseer, was ‘stone’ hand, and made up the ‘formes’ ready for the pressman, who came at 5 a.m. to work off the edition. With him, of course, came the P.D. One hand had to stay behind to assist me in making up the formes.

One had to be careful. If a forme were smashed, it could be turned into Printers’ Pie. ‘Making up a forme’ consisted of making the type into columns, and the columns into pages. The pages were ‘locked’ into ‘chases’. Two pages of double demy were locked in one strong iron chase, with an iron bar between the pp. It took two men to lift it on to the printing press.

The front and back pp. were printed the night before. Our printing presses consisted of a double-demy Albion, and a foolscap folio Albion. That was all. We had no machines. There were in existence two kinds of presses. – the Albion (left, above) and the Columbian (above right).

The Albion worked with a very strong steel spring to lift up the platen.

The Columbian had a spread-eagle lever on top which did the same thing.

We had a small book-binding plant, with an old-fashioned ‘plough’ for cutting the edges. Guillotine were not then invented. Neither were treadle printing machines.

As I have said, my ex-mate, Harry H., was sharing my tent with me again. He thought himself extremely fortunate to get into the office at a salary of Three Pounds stg. a week. He did his weekly washing on the ‘Sawbath’, being a Scotchman. (Possibly it’s not like a typical public bathroom, but more for people who work in jobs where they get dirty so at the end of the shift they’d go in there to clean off dirt from themselves or their work clothes.)

One day I discovered a lovely creek of beautiful clear water, away back in the scrub. Telling him of this, I, one Sunday, guided him to the spot. He had his washing and my big prospecting dish with him. I steered him straight through the thick scrub. The distance was no more than one-third of a mile. Harry H. grumbled at the ‘roundabout way I was taking him’!

To show what kind of a man ‘Harry H.’ was, I may as well record the following: –

One day, in the office, Bill Riley, the pressman, had had a drop too much from the brandy bottle on the stone. He was printing a small quarto poster that I had set up.

In a case like this, the roller boy – i.e. Printer’s Devil (a young apprentice in a printing house, particularly during the era of manual typesetting. These apprentices performed menial tasks like mixing ink and fetching type) – should be extra careful.

But Bill, who was quite irresponsible, kept calling for more ink. ‘Harry H.’ responded with ‘more ink’ – which, to make matters worse, he did not ‘work up’ (i.e. distribute evenly) on the ‘table’. He gave about two dabs with the roller on the ‘forme’ till the type was chock-a-block with thick ink.

When Bill became sober next day and saw the job he had printed, he almost wept! The ‘forme’ had to be thoroughly cleaned with lye – we used pearlash (Pearlash is known for its ability to react with acids or heat to produce carbon dioxide, which helps dough rise. It was a precursor to modern baking powder) to make our lye – and the job printed over again.

Thus we see the diversities in people. – and in nationalities.

Anyhow, I had no time for ‘Harry H.’ after that – although I still befriended him, to my later loss. One day ‘Harry H.’ preceded me in walking along a narrow track leading to our tent.

A tree stood by itself after a clearing had been made, the debris lying thickly about. As he passed underneath it, I heard an ominous cracking overhead. Instinct told me the limb was falling. ‘Harry H.’ stopped to look up. I yelled at him to run like –– well, the dickens, (an old-fashioned word for the devil) if you like!

Anyway, I didn’t mince my words, which were so vigorous, that ‘H’, omitting to look upwards, jumped nearly out of his boots! and ran as if Auld Clootie (a Scottish term for the Devil) were after him! And at that instant the branch crashed to the ground on the spot where he had been standing. I had backed the other way. So no harm was done.

One of the proprietors of the Grey River Argus – Mr Moore – was leaving for Ireland. Before going, he gave a banquet in the office to all hands, I among the number. The toasts were going along, ‘Harry H.’ got merry, and was troublesome. I was drinking a non-intoxicant – to wit, ginger wine. ‘Harry H.’ officiously poured brandy into it, and I threw it away.

By and by, as the spirit went down ‘H’s’ spirits went up, and I had to take him out and steer him for my tent. On the way, we passed a ‘pub’. At least, we didn’t pass it at first. He went in, and quarrelled with an Englishman – a painter by trade. He also was painting his nose red.

Let me here say that my ex-mate, ‘Harry H.,’ was not a drinker, but in this case he over-indulged at the banquet because he did not have to pay. I parted the two, and lugged ‘Harry’ along by the arm. By and by, we had passed the wooden buildings, and got to the edge of the scrub and swamp. But by this time ‘H.’ had collapsed.

So I lifted him on to my back, spread-eagle fashion, and wound my way with my burden, like another ‘Pilgrim’, in and out among the old shafts, where a false step would have sent us into the water a little below – (none of these shafts were more than six or eight feet deep) – around the creepers, over others heaped on the track, through the muddy swamp, to the tent door.

Inside, I lay him down gently and tenderly, when he fell into a deep sleep. Soon I heard a noise as of some one scrambling through the scrub, and a sound of swearing. I went to the tent flap to investigate when up came the Painter! Dark as it was, he had found his way there. ‘Where’s that lurid Scotchman? I’m going to smash him!’ he hiccoughed out to me.

Now, I always was and always am a peacemaker – unless imposed upon too much. So I took him gently by the arm and said, ‘He’s asleep. Run along home now, and come in the morning and give him a good thrashing.’ ‘All’r’, ole fellow, I will! – So long! – you’re a brick!’ Thus I made the peace between them. The Painter was so drunk that I knew he would remember nothing about it in the morning. And I saved my friend ‘Harry H.’ a thrashing.

Little things often turn the course of a man’s life. This was the case with my Scotch friend.

Next morning he was very ill. Notwithstanding this, he ate two hard-boiled eggs for breakfast. Then he had a dreadful stoppage of the bowels.

I went to the hospital for a doctor, and also to see if I could get him admitted there. But the place was ‘full up’ with rheumatic patients. The doctor accordingly visited him at my tent.

The patient suffered agonies for a fortnight. I purchased at a cost of Thirty Shillings, a single mattress for him to lie on.

At the end of a fortnight, I paid his passage-money, amounting to Nine Pounds, out of my own pocket, and put him aboard a Two-Hundred-ton schooner bound for Melbourne.

I also lent him money to assist him in starting a business in Bourke Street, Melbourne, making his indebtedness to me something like Thirty-Two Pounds sterling. That was the last I saw or heard of him for very many years.

Stories At Greymouth

While referring to this Socialistic democrat, I will mention an incident concerning him which happened after I had left the Coast, but which has never been in print.

Reefton was not in existence while I was in New Zealand. The Inangahua district was an undiscovered waste of vegetation. But, afterwards, gold was found there between the heads of the Grey River and the Buller River. Then the town of Reefton sprang up.

That was the first place where reef gold was discovered. My brother George went there, and, in conjunction with another man, started a newspaper which they named The Inangahua Herald.

Dick Seddon went there as a digger – he and a mate. ‘Dick’ had a parcel of gold – about sixty ounces – in a trouser pocket. One night, Dick’s mate saw a slit being made in the tent with a knife, and a man’s hand coming through. Gripping the wrist with both hands, he called out to Dick.

Seddon jumped up, rushed outside, caught the man, recognised him, and both of them gave him a good thrashing. This punishment being accomplished, they warned him to clear out within twelve hours, or it would be the worse for him. He went!

One day a young man was camped on the South bank of the Arahura River, which we crossed on our journey to Greymouth. Another man came up and slashed his tent into ribbons with his bowie knife.

An Irish woman, seeing this from the opposite bank, lifted her petticoats, waded across the river, and offered to hold the cantankerous one while the owner of the tent gave him a sound hiding. The chivalrous female and the youth did, between them, make it very unpleasant for the aggressor.

At some Greymouth sports which I attended, one event was a running long jump. I did not enter, as I never expected I could possibly win it, there being so many athletic diggers about.

However, one contestant made the ‘enormous’ jump of twelve feet, and won the prize! I was disgusted. I myself could jump a distance of ten feet four inches standing. When the sports were over, I told Jack R–– that I thought I could beat that record.

To prove it, we went down to the river strand, and with my first running long jump I cleared sixteen feet six inches. So it was a case of ‘nothing venture, nothing win’. By my jump was really nothing, for the record long jump is over twenty feet.

When my brother George followed me over to New Zealand, I was unaware of his coming. Sitting in my tent one day, reading a letter from my beloved, I heard someone knocking at the upright pole near the tent flap. I called out, ‘Come in and see the live lion stuffed with straw!’ And, lo and behold! George entered.

I made him welcome, and housed and kept him till he started on his adventures.

One day, going up the right bank of the Grey River with him, we came to a by-stream named Eel Creek, where the Maoris caught eels in wickerwork baskets We examined the small, deserted, Maori hut there. Near the hut was a garden.

I picked a lot of radishes, took them home to my tent three miles away, and ate them with salt for my tea. I afterwards learnt that they were turnips. They were so small and hot, that they were as good one way as the other!

At a Maori encampment, one day, I saw three handsome Maori women showing their well developed lower limbs to some curious and interested white men. The women were good tempered, and thought it a fine joke. I frequently had conversations with the Maori chiefs, and tried to learn some of the language from them.

I obtained the following interpretations:–

Supplejack (creeper) Kurrie-how.

Basket…………………… Kit-thie.

Whiskers………………..Pah-how.

Hair……………………… Hupu-Koo

Fingers…………………..Ding-a-ring-a

Cheek…………………… Pap-ar-ing-a.

Nose…………………….. Ish-sha

Eyes…………………….. Kun-o-wie.

Eyebrow………………. Kum-oo-Rum-oo.

Forehead……………… Dlie.

Ears……………………...Thuringa.

Leg………………………. Thwhy-why.

Head……………………..Thing-aring-ar.

Dirt, or mud……………T’winovar.

The earth……………….Th movar-cutava. The range of hills nearby Th-moug-wa

Water…………………… Th-why-ee.

Horse, dog, etc. ………Th-Curr-ee

Fire……………………… T’-a-chk-Ke

Bread…………………… Kie-Kie.

The chiefs were nice, mild, fellows to all appearances. But it is more than probable that they were the offspring of murderers, and even cannibals.

Like Australia, New Zealand had no edible fruits or nuts of any kind. There were few birds, the Maori hen being one, but they were very scarce. Therefore, before Captain Cook’s time, the inhabitants lived upon what they could procure from the waters.

Then, Captain Cook having landed pigs for their benefit, they had those useful animals as an addition to their larder.

Seals were numerous in the southern parts, and diggers obtained plenty of these below Okarito. Then, there were mutton-birds on certain islands.

But on the Grey River, eels and fish (whitebait) were the staple foods before the advent of the gold-diggers.

With regard to the Maoris being murderers and cannibals, on Captain Cook’s second voyage to New Zealand, in 1772, Cook himself, in the Resolution, of 462 tons, and Captain Furneaux, in command of the Adventure, of 336 tons, a boatload of the crew of the latter were murdered and eaten at Massacre Bay, near Nelson. That was the Bay we steamed across after leaving Nelson for Hokitika.

The Maoris in the North Island made incursions into the Middle Island in search of greenstone – otherwise jade – used in making stone axes, other implements, images, &c., before the Whites took possession. And they came down from Massacre Bay way – following the coast, of course, the interior being inaccessible.

They came down south as far as the Hokitika River, killing and taking prisoners the original inhabitants, but no doubt keeping those fine women that I saw for themselves.

Two chiefs – Niho and Takerei – settled at the mouth of the Grey River. As this last murderous raid took place only thirty years previous to my arrival there, the men and women whom I conversed with were, no doubt, their descendants, and the men may have been some of the original raiders.

Greenstone was found in abundance on the West Coast I had a piece once weighing ten or twelve pounds; but, with the indiscretion of youth, I threw it away like I would any other stone. But I bought my beloved Marianne a very handsome gold brooch set with a large piece of flawless greenstone. And I shall never forget how her beautiful eyes glistened as I gave it to her upon my return to Adelaide.

Its cost was Seven Pounds Ten Shillings. I also bought myself a watch-chain set in gold. The greenstone was translucent. This I gave to my brother Alfred, who soon got rid of it, pendants going out of fashion.

But I bought myself another one of inferior quality, the stone being dull and lusterless. There was a deposit of this jade between the Grey and the Teremakau Rivers, some distance back from the shore. A town of the same name sprang up there afterwards.

In course of time, as civilization progressed, a racing speculator, named Hamilton, came over from Victoria, and a racecourse was cleared on a muddy, densely-thicketed flat four miles up the river Grey.

We did all the printing for these events, of course. As no overtime was paid for in our office, one thing troubled the proprietors.

They did not know whom to ask to come back and work all night to set up the four-page double-large race cards, in solid ‘nonpareil’ – the smallest type in the office. The ‘copy’ would not be ready till ten o’clock at night, and the cards had to be set up and printed by eight next morning.

Seeing their predicament, I told them that as I had charge of the jobbing department, I considered it my duty. They were relieved – especially so, as they knew they could rely upon me to turn out the job sans errors. Being a proof-reader, that was easy.

A proof-reader on a newspaper has to correct everybody else’s errors.

The Race Committee did not finish arranging the programme till ten p.m. each night. Accordingly, I went to Moorhouse’s Hotel, on Mawhera Quay, at that hour, got their ‘copy’, and returned to the office in Boundary Street. Then I set to work.

The title page was already set. The other three pp. I put into type, pulled proofs, read them, did all corrections, imposed the formes, and had everything ready for the pressman – who came at six a.m., with the Printer’s Devil, and they had the cards printed by eight a.m.

This was done every day while the racing lasted. I attended the races one Saturday afternoon. Coming back, a young lady on horseback, going full tear along the gravelly strand of the river at an open spot, nearly ran me down.

The horse twisted me around like a teetotum, but I was uninjured. By the way, this first racing event on the West Coast must have been a failure financially, for the promoter went off to Victoria and forgot to pay the accounts!

The storms on the West Coast were sometimes very violent. One day I myself was caught in a very high tide, chiefly caused by the strong, continuous wind giving the tide a helping hand – or shove – landwards. I had to take refuge on one of the highest shingle-and-sand ridges south of the river’s mouth.

A girl of about sixteen, whom I accidentally encountered there, was in a similar predicament, and I assisted her to safety. The residents of Greymouth were in dread of tidal waves, which had played havoc with the Island of St. Thomas, in the West Indies, about that time.

Everybody was going to make for the back range on the indication of danger. But tidal waves don’t usually send out advice notes to say they are coming. It is generally a case of ‘Here I am!’

Some pleasant walks I had on Sundays with a man of my acquaintance. It was from Greymouth to Darkey’s Point – a distance of six miles – the place before mentioned, shown on the map as Point Elizabeth.

My first tramp with my friend – a storekeeper – over the wide shingly beach was interesting. Gold had been found at the Point, and wood-and-calico stores were being erected pretty freely facing the beach along the edge of the scrub. Although it was Sunday, the sound of hammers resounded as we wended our way along the coast.

The Greymouth range was the background, running diagonally, with very steep sides, towards the sea, and eventually plunging into the waters of the ocean six miles from the Grey River. Hence the name of ‘Point Elizabeth’ – after some dearly-loved girl, no doubt.

The stores that were being erected, faced the sea, as hinted at before, there being then no road. The strand was a very rough shingle bed about half a mile wide from the scrub to the rolling and curling waters of the great South Pacific Ocean.

The friend with whom I was tramping on that beautiful day was accosted by a very interesting young girl of his acquaintance who happened to belong to one of the then-being-erected stores. After a long chat, during which she sat down on the gravel with us quite sociably, we proceeded on our way.

Reaching the Point, we found the cliffs came down right into the sea. On another day that I was there, with a mate from our office, being thirsty, I went to a stream trickling down some sloping rocks to assuage my thirst. While drinking the cool, clear water, I saw a tiny nugget of rich-colored gold beneath my lips on a ledge of stone. I captured it and looked for more, but unsuccessfully.

As we had no dish to pan out the stuff with, we were unable to try any of the ‘dirt’.

Much gold was found above that spot, in terraces, the terraces being ancient seashores. Since that time, the New Zealand Government has been working a coal mine there.

The range consists of massive and solid carboniferous limestone, the same as at Greymouth. A road has also been made along the foot of the range from Cobden, on the Grey, to Point Elizabeth. Fifty years after my first visit to Point Elizabeth, and while the (then unopened) coal mine was in full swing, a tragedy was enacted there which reminded me of old times.

Greymouth Stories 1867-1868

After ‘H’s’ departure for Melbourne, the proprietors of the Grey River Argus got a brither Scotchman – a brother-in-law, in fact, of one of them – to take his place as roller boy.

Bill Riley, the pressman, was quick and smart, running off three hundred papers an hour on the d. d. (double demmy) Albion press.

The Scotchman was slow. He also had the habit of putting his inking knife on the lower framework of the big press after spreading the ink on the table with it. I warned him that he took the risk of having his hand crushed. He took no notice whatever. Bill was too busy working the press to look after him.

Then the catastrophe happened. Bill rolled the heavy, five-cwt, castiron table, with the ‘forme’ on it, under the platen, and caught the poor fellow’s hand against the iron pillar of the press, crushing it badly. He was under the doctor for months, and was not taken on again. A slow man is of no use in a printing office!

About this time a tall, lank, tough, wiry, fellow named Jack R__. from San Francisco, California, was his successor. He, with his father, had caravanned it from the Eastern States of America to the Pacific Slope during the stirring days of the gold rush to California before there were any railways there.

Caravans in those days were attacked and massacred by Red Indians at every opportunity. Brigham Young and his Mormonites, in conjunction with the Indians with deliberate cruelty and treachery, murdered a whole party of emigrants – all excepting a few children, who, so he thought, would not remember the awful deed. It is known in history as the Mountain Meadows massacre.

It occurred in 1857, whether before or after Jack R – and his father crossed I am not aware. I met Jack in 1866, and the massacre occurred in nine years before. So I am inclined to the opinion that his caravan passed after that dreadful event. One hundred and fifty men, women, boys, and girls were assassinated in cold blood by these Religious fiends. Talk about a God in heaven to prevent such horrors!

Twenty years afterwards – in 1877 – an active leader of the band – a Mormonite named John D. Lee – was tried for his part of the crime, found guilty, and executed. Brigham Young himself died in that year. His age was 76.

Jack R – told me of his adventures on that great trek of over three thousand miles. He brought with him from California an Indian suit of buckskin, with hair like that of human scalps running down the trouser-leg seams.

Dressing himself in this, I on several occasions accompanied him through the main streets of Greymouth of an evening.

So many nationalities were there, with all sorts of fashions in clothes, that we did not attract much attention. In those free-and-easy diggings days scarcely anyone wore braces.

Our tailors made our trousers to fit tightly over the hips, and thusly they were kept in position. But we all added a saddle-strap.

Diggers from Mexico and California wore around their waists silk sashes, Spanish fashion. Fine fellows a lot of the diggers were.

Above: Boundary Street and the Mawhera Wharf/Quay. People waiting at the wharf in Greymouth during a flood

One day, I saw little Stark – a Scotchman, working in the Grey River Argus office as compositor and reporter – standing on the footpath of Mawhera Quay looking up at the broad back of a giant Englishman quite seven feet high, and big in proportion.

Stark himself was about five feet high, a real decent sort, with a good head on him.

Upon my coming up, he looked at me, and then at the giant with a look of admiration upon his honest countenance, and observed: ‘There’s a fine specimen for you, Harry!’ I said: ‘My Word!’ I don’t know whether the giant heard us or not.

Alas! Little Stark died a few years after that. He took brandy neat, half a tumbler at a time. But he was never intoxicated. His was a good life lost.

He left a nice little wife to mourn her sad loss. She came all the way from Scotland to marry him. Brandy was the curse of those days. Gin also. Now it is whisky.

It was a merry life on the West Coast for those who chose to throw their money away and go the pace. There were eight dancing saloons in the town of Greymouth. In each were eight girls at the disposal, for terpsichorean purposes, of any man who chose to dance with them. Entrance, free.

The saloons were crowded every night. A man went up to one of the girls and took her as his partner, whether she liked him or not. If she refused him, the chances were she would get the ‘sack’. But, of course, he had to be a respectable man.

THE ‘GREY RIVER ARGUS’ OFFICE.

THREATENED ATTACK BY DIGGERS.

Threatened Attack on the Grey River Argus Office by Two Hundred Stalwart Diggers.

– Pulling down the Office, and Cutting off our Hair with a Knife!!! –

Things were lively on the West Coast of New Zealand in the middle Sixties of the nineteenth century – 1866 – when gold was first discovered upon its dreary and inhospitable shores.

On one occasion, in the year mentioned, the office of the journal I was engaged upon – the Grey River Argus – was threatened with destruction by as fine a body of men as one could wish to see.

They were anxious to catch every one of us connected with the staff, to perform a certain ‘barber’ous operation upon us – to wit, cut our luxuriant crops of hair off with a knife! Very nice!

We had to get the Argus out despite floods, fires, or riots. One of us went to a spy-hole in the front window occasionally and watched the threatening crowd in the bed of the very wide creek yclept Boundary Street. Stalwart fellows they all were!

They must have heard of our defence preparations, for at 12 noon, after keeping us on tenterhooks for three hours, they had not come to the attack. There were two hundred of them.

At the hour named, they adjourned to Kilgour’s Assembly Rooms on Mawhera Quay, and fined the editor One Hundred Pounds – which I need hardly say was not paid.

These men had, just before this, pulled down the canvas town of Okarito, south of Hokitika – that is, all but one grog shanty, where a barman defied them with a loaded revolver. That shanty also belonged to Mr . Kilgour.

This Okarito attack was the result of a wild-goose rush organised by a digger named William Hunt, and was the indirect cause of the discovery of the Thames Goldfield near Auckland, on the North Island.

Hunt had been insulted by the diggers, and he had determined to have his revenge. He accordingly reported the find of a mythical goldfield, and took them over hills and ranges, through swamps and forests, till most of them had fallen exhausted by the way.

Then giving the slip to the hardier ones who had stuck to him, he took a short cut to the coast near Okarito, boarded a schooner, and cleared out for Auckland.

There he discovered the Thames Goldfield as mentioned.

Left: The men of the Shotover Mine. Clockwise from bottom- George Clarkson, William A. Hunt, William Cobley, John Ebenezer White _Shotover Mine at Thames in 1867,

Above: The new Battery at the Shotover. Miss Hunt christened it the 'Goldfinder' on 21 July 1868

When the exhausted diggers discovered the trick that Hunt had played them, and that he had got away scot-free, they returned to the coast and levelled Okarito to the ground.

And they intended doing the same to the Grey River Argus office, but thought they might be shot (see story above).

Hunt afterwards became a wealthy man. But, losing his wealth, went in later years to Western Australia, where he died in poverty. The Okarito incident shows the value of a loaded firearm as a rogue-subduer.

At this period, murderers were roaming about the West Coast seeking to garotte any victim who might have a little money on his person. One gang strangled twenty-two men in my neighbourhood. This was on the confession of one who turned Queen’s evidence.

I escaped them, being too boyish-looking to attract their serious attention. Yet I always had more money on me than any of the men they murdered. As I have before mentioned, they stole my revolver, but left me unmolested.

I afterwards found I had some narrow escapes from getting into their clutches, as I was prone to take long walks by myself, both on Sundays and after dark. They had other lairs and bases besides Greymouth.

On the day that one of their victims was being buried in Greymouth – (the poor fellow’s second burial) –

I walked up the right bank of the river six miles, and looked down upon the little shallow grave where the bushrangers had first buried his body after throttling him. It was that of young Dodgson, a surveyor, whom they mistook for Mr. Fox, a gold-buyer of the Ten Mile.

My brother George was with Mr. Fox at the time, his intention being to buy the business.

On that Sunday afternoon, whilst returning to Greymouth, I and the companion who accompanied me – Jack R – re-discovered one of the murderers’ lairs by the trackside. I had often walked by it alone, little knowing who were lurking there.

The lair was invisible from the track, which passed through dense scrub.

Some people in Greymouth went sick with horror when the atrocities were brought to light. Amongst them was Jack Keogh, one of our proprietors.

Mr. Shaw, the mayor of that town, swore in one thousand special constables to preserve the peace there. I heard him speak in Kilgour’s Assembly Rooms in Greymouth one evening.

Standing on the platform there he said he expected to be shot where he stood, but he would do his duty whatever happened. Nothing happened to him, however.

From our own office, our editor, W. H. Harrison, stood as a candidate for Parliament in the Canterbury Province. He was defeated.

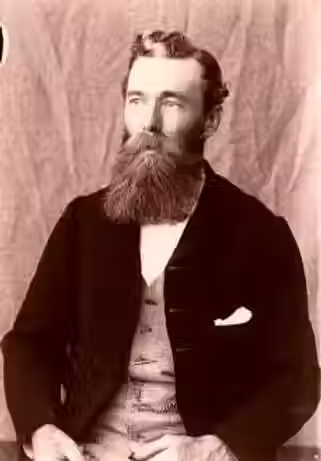

William Henry Harrison (New Zealand Politician and Journalist):

He was born in Leeds, England, in 1831 and later emigrated to New Zealand.

He worked as an editor for several newspapers, including the Grey River Argus and the Wellington Independent.

He also served as a Member of Parliament for Westland Boroughs and Grey Valley.

His political career ended after he advocated for prison labor to build a harbor, which was unpopular with his constituents.

An M.P.’s salary was Three Hundred a year. The Superintendent of each Province received One Thousand a year.

A carpenter named Dale, from Adelaide, a great temperance advocate, also stood, and had to stand down. One writer in our paper said that a great heap of unused aspirates (Ahem!!) was found in a corner of the room after one of his orations! But Dale had a thick hide.

With the inner workings of the Grey River Argus I was, of course, intimately connected. After I had been there some time, I was given charge of the inside department, including the jobbing and newspaper. Thus I was thrown into direct contact with all hands, including the editor and the proprietors.

I had to hunt up the editor – Mr Harrison – for copy – copy – copy! In fact, we wanted an ever-flowing stream of it! Harrison would write a leading article of six folios octavo in a very short time. But he gave us great trouble; and I was the one who had to hunt him up.

Many scores of posters, double-demy broadside, of the sailings of the steamboats to Melbourne, I set up. I remember the names of the following: – Claude Hamilton, Alhambra, and Gothenburg.

The latter, if I remember rightly, was afterwards wrecked coming from Port Darwin to Melbourne, when many South Australians were drowned, among them being the Hon. Thomas Reynolds, nicknamed ‘Teapot Tommy’ by our satirical papers, he being a temperance man.

In February 1875, S.S. Gothenburg was wrecked in a storm on the Great Barrier Reef off the north coast of Queensland. Twenty-two people survived in three lifeboats.

In our office at the Grey we printed various things. One long job was actually a book. It was also my duty to design and set up a double-demy sheet almanac every year.

Jack R––, our new Printer’s Devil, chummed with me to a great extent, we being the two juniors, although he was several years my senior. He was a strict teetotaller, but a great gambler.

During election times I have worked twenty-three hours out of the twenty-four – and received no overtime pay for it, either!

I happened thus because the election speeches of the night before had to appear in the paper next morning. None of us growled; we were a happy family.

Owing to these long hours, I had a narrow escape from being burnt to death in my tent in the small hours one morning.

I had a candlestick made of three nails knocked into a piece of deal close to my head. I lit a piece of candle in it, and then tumbled off dead asleep before I could get into my bed on the platform of logs. The candle burned down, the grease – tallow, not sperm, then – spread, the wooden candlestick was consumed, and the place was burning all around my head, and close to a canister of gunpowder under my pillow.

Just at this juncture, the corner of the ‘fly’ overhead, above the tent, broke away in the storm. The rain came in through the thin calico of the tent and extinguished the fire. That was the wreckage I saw when I awoke from a profound slumber!

Boundary Street, Greymouth in flood 1869

When floods and freshets came down the river, we worked sometimes up to our knees in water in the office, never knowing when the whole building would collapse, like others across the way.

For, as I have before mentioned, our sunken street was once at outlet of the Grey River, which broke into its old by-channel when the flood waters rose over the barrier at the wharf.

It was named Boundary Street because it was on the boundary line between the Government township and the Maori township – or the leased township and the freehold township.

Schooners and steamers were wrecked along the coast through missing the river entrance with its ever-shifting bar. A schooner, when stranded, was always sold by auction to the highest bidder.

If her keel lay towards the ‘curlers’ and her deck to the shore, she might bring a sum of Two Hundred Pounds. But if she lay with her deck to the waves, a Five-Pound Note might buy her.

The steamer, all iron, I mentioned as having broken in two was totally lost. But another iron steamer of fairly large tonnage was thrown, during a very high tide, right on top of one of the sand-and-shingle hills bordering the seashore, and sat there on an even keel as comfortably as possible!

Some enterprising man bought her for a song, laid down ways a mile long, and successfully launched her into the Grey River, when she was immediately worth Five Thousand Pounds.

One schooner I saw miss the bar. She was caught by a curler, turned turtle, and was never seen again, having drifted northward along the coast to uninhabited parts. The crew were washed ashore and saved.

The waves rolled in on the shore in a slanting direction. Thus if a schooner missed the narrow entrance to the river, she hit the shore on the slant and drifted northwards. And there we no inhabitants between the Grey River and the Buller River, fifty miles further north.

‘Dick’ Seddon – afterwards called ‘The King of New Zealand,’ now deceased – landed in Hokitika the same year that I did. He took to public-house keeping, but also dug for gold. He was a big, burly, fellow, constitutionally strong as a horse. Such men are favored!

Seddon was to dominate the New Zealand political landscape for the next 13 years. He remains this country's longest-serving premier or prime minister. Seddon was first elected to Parliament in 1879 for Hokitika, and later represented Westland.

After leading the Liberal Party to victory in the 1893 election, Seddon consolidated major reforms to land, labour and taxation law that had previously been thwarted by the upper house.

He even took credit for enfranchising women, a reform he had opposed.

Seddon’s five consecutive election victories have never been matched.

At his peak, he exercised almost one-man, one-party rule, but the quality of his ministry declined as he monopolised important portfolios and meddled in the rest.

New Zealanders were shocked when he died at sea while returning from Australia in 1906; famously, his last telegram read: ‘Just leaving for God’s own country.’

More Greymouth Adventures

The following is the newspaper report, dated November 9th, 1917: –

ROBBERY UNDER ARMS

Two men shot One Fatally Thieves Abscond with £4,000

‘A sensational robbery was perpetrated this morning on the Point Elizabeth road, Greymouth, recalling the Burgess, Kelly, Sullivan, and Levy gang’s exploit at Maingatapu* [Maungatapu], between the Wakamarina goldfield and Nelson, when several men were killed for their hard-won gold – Burgess, Kelly, and Levy subsequently paying the penalty on the gallows.

It seems that Mr. J. James, manager, and Mr. William Hall, a clerk, left Greymouth for the state coal mine in a motor car driven by Mr. John Coulthard, taking about £4000 for the payment of wages at the mine.

At a point on the road near a spot called The Camp, the car, turning a sharp corner, ran into a box ladder placed on the roadway, the obstruction pulling up the car.

A masked man sprang from a dugout nearby and called out ‘Hands up!’ Mr . Coulthard endeavoured to remove the box and was shot. He rolled into the gutter, dead.

Mr. James then leapt out, intending to shift the obstacle, but was struck by bullets in the thigh and leg, a third grazing his hand.

‘When Mr. Hall, who is paymaster, heard the robber’s command ‘Hands up!’ he refused to obey, but reached for his revolver and fired two shots, while the robber blazed away at short range with a revolver in each hand.

Mr. Hall believes he hit his assailant, who seemed to be wearing protective mail. Mr. Hall was hit in the arm, and two bullets pierced his chest. He has been taken to the hospital, and his condition is regarded as hopeless.

The nearness of the assailant is attested by the fact that Mr. Hall’s clothes were on fire when he was picked up.

‘Meanwhile, Mr James fainted. On his recovery, the car and the robber had disappeared. Two cyclists approaching the spot heard the shooting, and then saw a man, carrying a bag, take to the bush on the other side of the railway, which runs parallel with the road.

‘The inhabitants of Greymouth are greatly excited. Two arrests have been made, but it is doubtful if the men are connected with the crime.

A similar obstruction was placed on the road a fortnight ago, but was removed before the paymaster arrived. Evidently the robbery was coolly premeditated.’

A further telegram stated: –

‘The preliminary trial was opened at Greymouth on December 2 of William Frederick Eggers ……..

Bank officials identified money found at the prisoner’s lodgings in Christchurch’ [on the other side of the Middle Island] ‘as part of the pay for the State Coal Mines.

He was identified as the man occupying an old hut near the scene of the tragedy. A piece of tin from this hut, discovered later in a coastal hotel bedroom occupied by the accused, put the police definitely on his tracks.

The paymaster, Mr. Hill, is not yet able to give evidence. His depositions were taken some days ago.

A bullet was extracted from his arm. But Mr. Hill is still in a critical condition, the lower part of his body being paralysed.’

I did not learn if this man was convicted of the crime. With regard to the ‘Burgess gang,’ Sullivan turned Queen’s evidence. He was jailed, but was afterwards let loose. For a full report of their murders, read on...

THE BUSHRANGERS' SIGNALS.

I Retire Gracefully from a Murderers' Trap. –

In 1866 a gang of murderers roamed over the the West Coast of New Zealand's Middle Island. Their location was the Grey River, their head-quarters the Town of Greymouth, a goldfields town then just in its infancy.

I was encamped in my tent, all alone, in swampy ground on the edge of thick timber, entwined with creepers. I was there before them. They came and pitched their tent about fifty feet from mine, a little further in the scrub.

My six-chambered revolver having been loaded a considerable time, I, one evening, discharged its contents outside my tent, replaced the firearm under my pillow, and went to work at the Grey River Argus office as a compositor, and remained at work till two o'clock in the morning.

Coming home that night in 'the small hours avant the twal., [presumably – before the hour of twelve] I turned in.

Getting up early, I noticed the tent was in some disorder. I searched for my revolver to reload it. But it was gone! I did not know then who had stolen it, although I had a suspicion it was the men in the outside tent, who, I had noticed the night before, had taken stock of me while I was firing it off. Three sinister pairs of eyes followed my movements.

But I learned the facts afterwards. The gang of murderers was composed of Burgess, Kelly, Levy, and Sullivan. Always when I took my walks abroad at night – which I made a practice of doing in order to get exercise – I carried my revolver in its holster on my belt under my coat.

I also had a bowie knife in a sheath. I am quite sure, however, I never could have got myself to use a knife on a man, even in defence of my life. It seems too brutal and unEnglish. I would rather have relied upon my fists and hands if I had nothing else.

But after the loss of my revolver, I carried a heavy pebble in each coat pocket to stun an enemy with. I found out afterwards that that would have availed me nothing against these cunning and methodical villains.

There were only two tracks out of Greymouth – one up the river, the other towards the beach, both through thick scrubs, the former mostly on a siding cut around the high bank on the right hand, that being a portion of the high timber-covered range, the range being one mass of timber and foliage from bottom to top.

For two miles up, commencing at the Gorge, through which the river ran, the track was cut around the range. The track therefore overlooked the river on the left hand. In places the stream touched the perpendicular bank along which the track ran – an easy spot in which to throw a victim overboard into the swirling waters!

In others there was heavy foliage between the track and the swiftly-flowing stream. The excavated track was elevated from thirty to sixty feet above the river. Anyone cast down by the bushrangers would either disappear for ever in the shrubbery or fall into the river, to be afterwards carried to its mouth, then over the bar into the ocean, and afterwards perhaps thrown up upon the shore.

Body after body was thus found, and general consternation prevailed. I carried my money – up to Thirty Pounds (above that sum I used to send on to Adelaide by bank draft) – in a pocketed pigskin belt beneath my flannel. With regard to the heavy pebbles in my coat pockets, I had resolved, upon the approach of bushrangers, that the first man would get the first or right hand pebble, hurled with full force, on the head, and the second man the left. Then I would have a run for it.

I was young – about seventeen – and green, but with the usual conceit of youth thought I knew a lot! Little did I know of the murderers' tactics, however! These came out afterwards.

Their plan was this. Burgess was the leader, and a brave man. Selecting one of the most daring of the band – mostly Kelly – he himself and the man chosen took up their station on the lonely track, first placing a scout at each end. The scouts were to signal to the two Executioners when a digger was coming along.

If two men approached together, they were allowed to pass right through, all the members of the gang just quietly stepping into the scrub for the time, where they were completely hidden from view.

When a man came along alone, the Scout signalled the fact – The two murderers then waited till their victim was within reach, when they pounced upon him like human tigers. They at once strangled him with a silken Spanish sash that many diggers wore around their waists those days, and either threw his body into the river or down the bank into the creepers below, or dug a shallow grave and buried it.

It made no difference whether the man had money or not, he was murdered in cold blood just the same. 'Dead men tell no tales' was their motto, and they acted up to it always. Every man they stuck up, they killed. None escaped.

So what chance would I have had? If two solitary men came along the track in opposite directions, and the Scouts at either end gave the signal that a traveller was approaching, the two villains in the centre stepped into the obscurity of the scrub and let them pass on their way unmolested.

Being on the scene of most of the tragedies, I had an intimate knowledge of them all.

And now to come to the point of this particular article. One evening, after the loss of my revolver, I decided to take a constitutional towards the beach, along the one and only track with the dense scrub on either side. The darkness was intense, for the timber growth stood up like a wall both right and left, the country there being flat.

The track went through this scrub a mile or more before debouching upon the beach. I took care to have a heavy pebble in each coat pocket. Swinging along on the crunching gravel, I had proceeded about half a mile when, suddenly, there arose upon the still night air a noise like the clinking of two hard pebbles together. It sounded clearly and sharply above the dull booming of the distant sea. There was one click only.

My senses being on the alert, I stopped immediately. Listening intently, and hearing nothing more, I concluded I must have been mistaken. So off I started again, when the same metallic was repeated. Then, getting wary, I just slowed down, gradually came to a stop, and stepped into the scrub.

Listening with all my ears, I peered up and down the track, but could see nothing, and everything was still and quiet except the restless ocean. I reasoned with myself. 'I must be a coward if a noise is going to deprive me of my walk.' So, being reassured, I stepped out of the scrub and resumed my journey. But I had no sooner trodden the gravel when the click sounded out once more. There could be no mistaking it now! It was a signal of some kind.

What, I did not know then. But I afterwards knew the meaning of it all. Being thus certain there was something in it, I argued again:

'Well, what's the use of running into danger when there is no necessity for it? Now, if I had to go down this track, I would go, and chance it; but as I am only out for a walk, I would be a fool to take the risk.'

Thus settling the matter in my mind, I stepped out on to the gravel and started homewards. As I did so, the ominous clicking was repeated. But by this time I was interested in it no more, and steadily pursuing my way, went back to my tent to within fifty feet of the murderers' abode, and peacefully turned in.

I wonder if I should have taken things so placidly had I then known that it was the 'murder gang' that was camped close alongside of me, and all of us in a lonely spot away from the other tents?

I was, however, only a beardless boy; and that was what saved me. The hair was growing on my face, but it was fair and so irregular that I shaved it off, and thus had the appearance of a beardless youngster.

Grown men never clean-shaved in those days. They wore ornamental whiskers, or at least a moustache. I really had more money on me than the murderers obtained from most of their victims. Sullivan himself confessed to no less than twenty-two murders on the Grey River and along the coast. No one ever knew what the total was.

At the Teremakau River, south of the Grey dredging operations for gold have been carried on since my time. I know a spot on the Grey River where tons of the auriferous metal could be obtained by deep dredging.

It is at a sharp, rocky bend – or, rather, elbow. But a coffer dam would be necessary to secure the prize. The stream there is wide – and deep and rapid near the rocks, where the gold would be found.

I have often stood upon the cliffs there and tried to throw stones across the stream when the river was low, but never succeeded. I have seen it a mile wide there when the floods were on. On the Teremakau River, some distance up, the Town of Kumara sprang up, fourteen miles from Greymouth, away back from the coast.

A tramway with wood rails was made from Greymouth, away back from the coastline, to Kumara.

I well remember a young man riding a horse furiously along this tramway track, when one of the horse’s hind shoes became caught under a sleeper, and the poor animal’s hoof was pulled off like a glove, with the iron shoe attached! The unfortunate horse had to be shot. The hollow hoof with iron shoes was brought to our office, where I saw it.

At the Teremakau River, at the spot where I crossed, an aerial cage on wires was afterwards inaugurated. The river Grey, and as a sequence the Town of Greymouth, were of course named after Sir George Grey, the then Governor of New Zealand. He paid the town a visit while I was there.

I had the honor of having printed for presentation to him a copy of the Grey River Argus, on silk. This, no doubt, is one of the heirlooms of his family. Our pressman, Bill Riley, was the man who actually printed it on the double-demy Albion press. And it did him credit, with just sufficient silk and no more. It was I who got the forme ready.

One day a golden pebble was brought to our office. It was just like any other pebble in shape but of pure, solid gold, without a flaw, and of a very rich color. Its value was Fifty Pounds sterling; its weight one pound troy.

I had the pleasure of holding it in my hand. It goes without saying that it was weighty for its size!

It was found in the bed of the Grey River – in the upper part – amongst other pebbles in the shingle. This nugget was raffled for. Jack R– and I went halves in a ticket, each paying ten shillings. That sort of thing was not against the law then.

Nowadays we are so goody-goody – so sanctimonious – that it is unlawful to raffle anything but an oil-painting. And why an oil-painting? I was present at the drawing.

A little girl drew the tickets from a barrel. The very first ticket drawn won the prize, which went to a little baker, who was in the habit of dancing and indulging in other dissipations the most part of the nights, and then starting work at his trade at three o’clock in the mornings.

I do not suppose the proceeds of that beautiful nugget of gold lasted him many weeks.

Knowing I was employed in the newspaper office, a Scotchman, who was rather illiterate, asked me one day how I managed to spell words correctly. I told him that, being a compositor on a newspaper, I had to.

In order to test me, he took up a fine dictionary he had there and called out words for me to spell. I said, ‘Go ahead!’

For a quarter of an hour he tried, and I spelt every word aright, of course; for a ‘comp.’ who couldn’t spell would not be ‘comp’ at all. ‘Now,’ I said, ‘I will tell you why I can spell correctly every word that is in that dictionary.’ He looked at me, puzzled. ‘Why?’

I replied deliberately, ‘Because I have the same kind of head as the man who compiled the dictionary.’

In this man’s employment – he was store-keeping, although a carpenter by trade – was a young Highlander.

He was tall, and very handsome, with the bloom from the heather still on his cheeks. Modest in the extreme, he was a gentleman in every respect. We were great friends, and were often together of an evening.

One night we had a friendly contest. It consisted in each putting his elbow on the table, clasping hands with each other, and trying to force the other’s arm down on to the table without lifting the elbow. We sat on chairs during the contest.

I myself was always a light weight. I then weighed ten stone ten pounds. He was a six-footer; I only five seven and a half. We gripped and tried our utmost. But neither was the victor.

For fully fifteen minutes we each strained our muscles trying to put the other’s arm down, without avail. Both our arms remained in the upright position, and we had to give up the contest.

I was strong for my weight in those days, as I always practised gymnastics to keep up my muscles.

When sixteen years of age I could carry a two hundred lb bag of flour in my arms with ease, and I have lifted a fifty-six lb weight above my head with one hand.

But my father could beat me easily there. For he could lift two of them – one in each hand – lift them slowly over his head, clink them together, and lower them again slowly. And he didn’t know he could do it until a bet was made by two others over it.

Whilst taking walks at night upon the upper track leading into the forest up the right hand bank of the Grey, I have distinctly heard the familiar Australian cry of ‘Mo-poke! Mo-poke!’

It emanated from the New Zealand owl, the owl itself differing from the Australian owl in having a different kind of leg. Both these owls – the New Zealand and the Australian – are known as mopokes.

Coal exists in unlimited quantities up the valley of the Grey. Brunnerton is the centre of production. It is only a few miles up the river. Whilst I was there the coal mines were only just in their infancy. Diggers going up the river made fires of the loose coal lying about on the surface of the ground. The mineral was brought down the river in ten-ton barges to Cobden, where there was a coal wharf.

Those barges were too heavy to be either rowed or sailed up-stream. They were poled up with long poles along the shallow edge of the river. But coming down, with ten tons of coal aboard, sails were set, oars were plied, and the centre of the swift current was chosen, when this combination of natural forces brought them down stream at great speed.

From Cobden the coal had to be shipped to steamers in the offing. Greymouth coal will always be expensive owing to the impossibility of making the river-mouth a port for sea-going ships and big steamers.

Westport, at the mouth of the Buller River, forty miles north, is, I understand, a good port, and most of the coal sent from New Zealand comes from there. The Buller River reaches up to the head of the Grey River, and the coalfields of both are really one huge field.

Since my time, a new and extensive coalfield has been found in the big timbered plains of the Grey River catchment area. Those parts were inaccessible then. The coal is of the best quality.

The generally-swollen river – with an average rainfall of One Hundred and Sixteen Inches a year – the great Southern Ocean beating directly into its mouth, with deep water outside, and a surf upon which no rowing boat or small yacht ever floated, greatly nullify the value of this vast deposit.

Moari Legends with regard to the Moa Bird were curious. This bird, now extinct, stood some fifteen feet high, had only rudiments of wings, like an emu and the African ostrich. The eggs were very large.

A Moari chief informed me that in old days these creatures came out of the forests into the native camps, picked up children, and ran away with them. The incensed Maoris then burnt the Kauri forests, and thus did away with the lairs of their feathered enemies.

As this happened in the North Island, this was additional evidence that my Maori informant was one of the raiders who descended upon the West Coast inhabitants and murdered them.

This also accounts for the fact that, in the Auckland districts at anyrate, Kauri gum is now found buried in the ground in tracts of country where no trees now exist. The conflagrations which destroyed the trees must have melted the gum from their bark and trunks.

And now, at this period, gum digging is one of the industries of the North Island. The text-books say that the Kauri pine exists only on the North Island. I think that is a mistake. I have seen thousands of what we all considered Kauris in the West Coast forests. They were exactly like the Kauri pines I came across in the North Island – the same straight stem, the same umbrageous foliage, the same conchoidal bark.

The white pines on the West Coast were also fine trees, with solid timber, but with spreading branches on top. Ship’s masts grew in these forests. They were cut down, rolled into the river, taken to Greymouth, and smoothed off ready for the ships.

It was a fine sight to see this noble timber rising out of the dense forests with stems absolutely straight. The text-books, I may say again, were written before any full exploration of the West Coast had been made, and so they may be inaccurate. Westland was then wholly inaccessible.

The high Southern Alps on the east prevented access that way – while the coast was too dangerous for boats to land. Therefore the only way to get into it was along the rough and almost impassable north. The rainfall, too, drenched the whole land.

This may account for the imperfect knowledge of the botany of the western portion of the Middle Island in those early days.

It was only through the discovery of gold that these physical difficulties were overcome.

One digger, young and good-looking, I saw down on his luck. He was camped near me. His partner had deserted him, and had gone to live with his family in a weatherboard house. The said partner’s daughters were fair and very beautiful. I took pity on the deserted man (like the young fool that I was) and succored him – to my sorrow.

After helping him in many ways, he told me that he thought that if he could purchase a boat, he would be able to get a living by becoming a boatman, ferrying passengers across the broad river between Greymouth and Cobden. Accordingly, I handed him the sum of Sixteen Pounds as a loan, and told him to buy the boat and make a start.

This shows I was no business man at that youthful age! I should have purchased the boat myself and leased it to him for a term. Or, better still, have minded my own business, and let him look after himself.

He bought the boat in his own name. Ever after that, whenever he saw me coming on the Greymouth side, he rowed over the river to Cobden, and thus gave me the slip! If I followed in another boat, at a cost of one shilling each way, he was nowhere to be found. He used to hide himself like a criminal – as indeed he was, for he robbed me of that Sixteen Pounds sterling, as I never saw it again.

Neither my business instincts nor my legal knowledge were keen then, it will be plainly seen. It must not be supposed that I let him off very lightly. For, whenever I had the spare time, I made for the landing-place near the Gorge on the Greymouth side. But it was always to see him scuttling across the water for Cobden in my boat!

However, I gave him many a pull back and forth over that river for nothing! Criminals are strange characters! They are the missing links between man and the ape. It will be millions of years yet before they evolve and develop into men.

He gained the boat, but the worry he had over it was not worth it. But what can one expect in this world? Darwin’s theory of evolution has long been proved a fact.

We are always coming in contact with people whose brains, and consequent morals, are no more developed than those of the ape from which they sprang in the ages long ago.

To the mate who had deserted me in Toi-Toi Valley near Nelson, I also, at first, sent half of my salary. My old, experienced, father in Adelaide, to whom I chanced to mention the circumstance in a letter, advised me to stop the remittances, which I did!

Then my former mate never wrote me again. Nor did he repay any of the money!

One tragic affair in the social life of the residents of Greymouth caused a sensation. A bank manager was living with a married woman of medium age, or fairly young – a very common occurrence on the cosmopolitan goldfields. He received a command from head-quarters to either abandon the lady or resign his official position.

For reply, he took a revolver and blew out his brains, pieces of his skull flying about the room. This shows the awful despair a man is in when he finds he has to give up the woman he loves.

Concerning this subject, one of the most distinguished members of our staff was living in the same way. She was the wife of another man. She died!

Our proprietors and all the staff – myself included – attended the funeral to show our sympathy with him. Let me say the gentleman in question was not one of the proprietors. The wife of one of the proprietors – she was a scotch young lady – put a crepe band on my hat for me on the occasion, showing her own and her husband’s broadmindedness.

Many of these women were deserted by worthless husbands. So who could blame them for seeking the protection of another man? The divorce laws were not so lenient as they are now. A woman can now get a divorce for desertion extending over six years – or so I believe.

My brother George was up at the ‘Ten-Mile’ on the Grey River, with Mr. Fox, the gold-buyer, when those awful murders I have referred to were being committed, and when Mr. Fox had a narrow escape from being a victim.

Afterwards my brother and Mr. George Giles, an Adelaide man of standing, went over the great Southern Alps on foot to Christchurch. There was a road from Hokitika.

They camped in the snow for several nights. George afterwards contracted rheumatic fever, and he credited its origin with that cold journey and the snow camps.

He tramped back, and when he returned I gave him shelter in my tent at Greymouth. When he appeared at my tent door, the soles of the Wellington boots that I had lent him for the journey were turned upwards through his tramping in the mud and slush so long. He was practically ‘walking on his uppers.’

Where Giles went to I never heard. But this I know: He borrowed the sum of One Pound from me when he went away; and I never saw it again! George afterwards started a Job Printing Office in Hokitika, which he kept going for many years, and did heavy work. This was after I had returned to Adelaide.

Then, later on still, came the Inangahua Herald, which he and another man started at Reefton, up the head of the Grey – where the first reef gold was found. George stayed at Reefton many years.

Poor George went much into society, and was very popular. He was Grandmaster of the Freemasons at Reefton, and was presented with a ‘jewel,’ the gold in which alone was worth Nine Pounds. Instead of saving money, he wasted it by mixing with and entertaining society people.

George came to Adelaide many years later, and died suddenly of Bright’s disease.

While on the Grey, I took nightly exercise on the nights I was free, by going up the river, or down to the pebbly seashore, the latter being a mile away.

A primeval forest at night comes next to an underground cave for blackness.

Nothing at all is visible. I took the chance of being caught by the bushrangers.

Before my revolver was stolen, I carried it in my belt, loaded, on my left side, and a sheath-knife on my right.

After the loss of my ‘shooting-iron’, I walked on the alert, with a heavy pebble in each hand, and knife in the sheath.

The stones were the ammunition I intended using upon an assailant. But a knife I could not bring myself to use on a human being.

I was walking into the murderers’ trap one night, but heard the signals, and backed out, with measured tread and slow!

My Valentine