Tilbrook Family Emigration

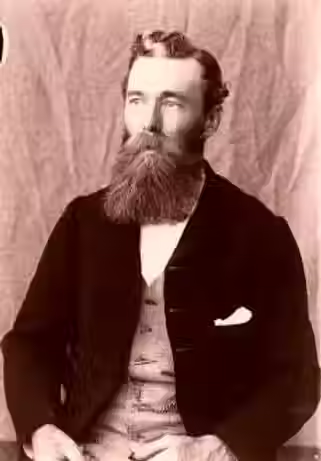

Henry Hammond Tilbrook became the founding editor of the Northern Argus in 1869, the newspaper of the Clare Valley, which was published until 2020.

Henry Tilbrook was born in Oswestry, Shropshire, on June 14, 1848.

and lived in Llandudno, Wales, from 1848

Tilbrook's father was a gamekeeper originally from Weston Colville, Cambridge-shire.

-

When Tilbrook was about six years old, in 1854 the family sailed to South Australia on the Albermarle.

-

He worked for a short time as a typesetter at the Register in Adelaide (1861-3)

-

as well as working as a lamb minder for a short time, for Sir Thomas Elder (1864). Tramped all over the same area (1865). Grocery delivery in Glenelg.

-

Worked at Ooraparinna Cattle and Sheep Run, far north of Wilpena (1865).

-

Enticed by the gold rush at the time, Tilbrook moved to New Zealand in February 1866 to try to make a living prospecting.

-

After having no luck with gold (in the rain), he moved on to work (1866-1868) for the Grey River Argus in Greymouth (first published 1865).

Shortly after returning from New Zealand, H. H. Tilbrook founded the Northern Argus newspaper in Clare, Northern Argus, first edition, 19 February 1869.

– HENRY TILBROOK LOST IN LONDON, AS A BOY OF SIX –

Lost in London when a Child. – Temple Bar. – 1854

While staying in London, England, at an aunt’s, with my father and mother, I was lost in the great City of London. That was about the end of August in the year 1854. I was then about six years of age.

A servant girl working for my aunt took three of us – my brothers and my insignificant self – out with her through the streets.

Aunt lived in a ‘Place’, a sort of side-court with a flagged floor, but no roadway. All the houses were many storeys high.

We had just come from the country. My father, Peter Tilbrook, had paid £150 for our passages out to South Australia, and we were on the point of embarking on the wooden sailing ship Albemarle.

The girl took us three boys out into the streets. She walked very rapidly. We turned in to Cheapside – otherwise The Strand. We went underneath one of the arches of the famous and historical Temple Bar, which, with its three archways, spanned the street there. It was upon it that they used to exhibit traitors’ heads on spikes after the criminals had been beheaded.

Temple Bar was erected in the year 1670, but re-erected and completed in 1672 by the great architect Sir Christopher Wren. In 1772 the last head fell from the Bar, as after that time no others were placed there [Vide Book I., p. 37, of ‘Old and New London’ in my bookcase. Also p.42 for illustrations showing Temple Bar as I saw it in 1854.]

Afterwards, – in 1878 – it was taken down from the spot where I saw it, and in 1888 re-erected at Theobald’s Park. I remember it well. As I have mentioned, it had three archways – one over each pathway and a larger one over the roadway.

Striding along, the girl looked straight in front of her, we following. From Temple Bar we crossed the roadway into The Strand on to the river Thames side of the street.

The buildings towered above us as I looked up at them. Completing her errand further along, the girl started for home, my brothers alongside of her, I following behind, as the footpath was narrow.

In The Strand, within fifty yards of Temple Bar, I saw something attractive in a shop window, and stopped to look at it. When I looked up again, I was alone! The girl had sailed along without looking back, She and my two brothers had, of course, disappeared through Temple Bar, and I was left there deserted!

I was a curly-headed kid, and although only six years old I remember everything – the exact shape of Temple Bar, the high buildings, and all. I had as much chance of finding my aunt’s place as I had of getting to the moon, for London streets are not rectangular; they run in all directions.

Stray kids were mostly kidnapped in those days by master criminals and trained for nefarious purposes. Some were wantonly crippled to turn them into efficient beggars; others were used as chimney-sweeps. Boys were made to climb up the insides of chimneys to sweep them out with handbrooms.

Imagine the turnings and twistings of chimneys in a city like London! I stood there helpless. I felt like a grown man, but desolate and hopeless. I gazed around very quietly, I made no noise. I knew I was lost, but said never a word, although hundreds of people were passing by all the time.

I moved away slowly from Temple Bar, I looked down an area grating and saw a man cleaning a pair of boots. I gazed at him with desolation in my heart. I remember quite well that I wished I was he, for then I would have somewhere to go. Then I wandered further down The Strand, away from Temple Bar, till I came to a narrow lane. This I afterwards learned was The Strand Lane.

Down this I walked till I came in sight of the Thames River, with shipping on its wide waters. Going down towards it, I was just on the point of emerging into the open, when I saw a Black Man! turn from the wharves into the lane I was in! and come towards me.

Now, in my home at Llangforda, in Wales, the maid who looked after us was always trying to frighten us by saying, if we were not good a Black Man would come and run away with us! Being one of those truthful and trusting youngsters who never thought of telling a fib, and believed everything that was told them, and being so young, I felt sure that that was the Blackfellow who was coming after me at last!

Even then, I acted like an experienced man. I knew instinctively that I must not run away. So I quietly turned around and retraced my steps, feeling every moment that this Black Man might grab me. But I would not run; neither would I look back.

I soon returned to The Strand, and went and gazed into the very shop window that was the cause of my being lost. It was also the cause of my being found! I stood about there a long time, looking around, not knowing what to do, and with a fearful load of desolation in my heart.

I was gazing at the opposite archway of Temple Bar, when who should I see come through it, and pass over the roadway straight towards me, but my father and my aunt! How pleased he was may be guessed under all the circumstances, And what a terrible load was taken off my mind!

We crossed the roadway together, passed under the same archway once more, then turned into a labyrinth of streets, long and short and twisting. In one long, narrow street was an old woman’s apple stall. The old woman who owned it was absent, however- But that did not daunt my aunt! She was a woman of action. She planked down some silver on the stall, helped herself to a liberal supply of apples, and gave them all to me, so delighted was she at my rescue.

FROM LLANGFORDA TO LONDON.

Through the Black Country to London. – My father having decided to leave England for South Australia, we left Llangforda – situated not far from Oswestry – for London. Railways had not long been in existence then.

My father had walked over the Britannia Tubular Railway Bridge, built by Robert Stephenson across the Strait of Menai, between the Island of Anglesey and the main land of North Wales, Carnarvonshire. That bridge was built in 1850, and we were journeying on one of the railways from Wales to London only four years later – in 1854.

I remember going through what I think was the ‘Black Country’, but of that I am not sure. At anyrate there were great factory chimneys, with clouds of black smoke hovering over all – making a dismal picture after picturesque Llangforda and Llangedwyn.

Being only six years of age, the journey was an awesome one to me. We went through the Bath Tunnel, which was said to be three miles long. The train took five minutes to pass through it.

Arriving in London, my father paid for our passages in the ship Albemarle, in the meantime lodging in that city with my aunt.

– FROM ENGLAND TO AUSTRALIA. –

– 1854 The Voyage from England. –

We got aboard the good ship Albemarle, and left London Docks in her on the 11th of August, 1854. Although only a small vessel of seven hundred and odd tons, the Albemarle was a fullrigged ship of three masts.

She sailed around to Plymouth Portsmouth to obtain barrels of fresh water. At Portsmouth we saw Nelson’s immortal ship The Victory upon which man-of-war he finished his great and glorious career at the Battle of Trafalgar on October 21st, 1815.

She was a noble sight, with her high decks and tall masts. There was a great crush of shipping at Portsmouth, and I thought the big ships there were going to run us down. Hot words passed between our captain and the captain of a large ship which towered above us. The big dog wanted the little dog to get out of the way; but the little dog wouldn’t!

Above: Young (Bishop) Augustus Short (1847), daughter Isabella Short (1860), and Mrs Short (1865)

Bishop Short came aboard at Portsmouth, for he and his family were also coming out to Australia. He was the first Bishop of Adelaide, and was consecrated at Westminster Abbey in 1847.

He was a short, sturdy man, with a rather irascible temper. He was a good boxer, well understanding the ‘noble art of self-defence.’ In fact, he once, in Australia, gave a bullock-puncher a taste of his fists. I well remember seeing Mrs Short, Miss Short, and Miss Albinia Short being hauled up from the little rowing boat on to the deck of the ship in a chair which swung high up into the air. The men climbed up the side steps or gangway.

It was very rough in the English Channel, but calm in the Bay of Biscay, where tacking! tacking! tacking! to get a way on was the order of the day and night.

We stopped one night at Greenwich, I might mention. What was afterwards termed ‘circular sailing’ was unknown then. Instead of going with the wind across the Atlantic Ocean to the American coast as ship captains afterwards did, we hugged the African coast as being the most direct route.

The consequence was we got into the ‘Doldrums’, and for days scarcely moved at all. Then when we reached the ‘Roaring Forties’ – that is, 40°S – the ship rolled so badly that the yardarms dipped right into the sea. The Albemarle was a slow boat.

We passed through a big school of whales. They were on all sides of us. They were monster animals – for a whale is an animal, a mammal, not a fish, As whales must breathe air like other animals, they have to come to the surface for that purpose. It is then that they ‘spout’.

I watched these leviathans about the ship with wonder. They had great black backs, and they spouted water up in great fountains. I was greatly afraid they would run into our ship and upset us.

One day, in the tropics, the sailors caught a shark fifteen feet long. They trailed a stout hook, baited with a great lump of pork, over the stern of the ship. I did not see the shark actually take the bait; but my father did. He said he was curious to see if the fish – for a shark is a fish – would turn on its back in the operation; so he watched closely.

He told me afterwards that the shark did not turn on its back to take the bait, but swam straight to it and swallowed it, hook and all, in its normal swimming position. Since then I have read of sailors denying that sharks turned on their backs when taking bait or attacking their prey.

However, I saw this monster shark being hauled on deck by the sailors. It thrashed the deck with its tail in a most vigorous manner, making a tremendous commotion, while a sailor skipped about with a hatchet in his hand, trying to get in a fatal blow – In this he was at last successful. I was much interested.

At another time, flying fish flew over the ship in large numbers, and many of these curious creatures fell on the deck, where, of course, young as I was, I examined them. They had very long, bony membraneous fins. They were being chased by either dolphins or porpoises – the latter, I suspect.

In one great storm, the bulwarks of the Albemarle were washed away, and the old ship was in a sinking condition in the morning. However, the pumps were set to work and she was saved. We touched no land all the way out, but saw land at different times.

We saw the Cape Verde group of volcanic islands off the coast of Africa. One mountain there is nine thousand one hundred feet high. We also passed another group of volcanic islands – Tristan da Cunha, in the South Atlantic Ocean. These belong to Great Britain – the former to Portugal. The island that we sailed close to [what] appeared to be bare rocks.

Once, towards evening, a ship came into view, but had passed by us by morning. On the West Coast of Africa we saw little white huts. I was permitted to look at them through a telescope.

Miss Short – (Isabella) – was a very active young lady, and very pretty, with a beautiful, fresh complexion. She announced on board that she was going to hold a Sunday school each Sunday. This frightened me so, that I ran away and hid myself amongst the cargo, which gave rise to the belief that I was lost overboard.

It was, no doubt, a great relief to my parents when I turned up again – after the school was over for the day! Afterwards I attended school regularly.

I remember, at the beginning of the voyage, all our people were sick except father and I. We stayed up, eating warm, boiled potatoes, with salt. I can remember the taste of them now! Our chief food during most of the journey was pea-soup with hard ships biscuits. How I detested the soup! It was thick and yellow, made with ripe split peas.

The drinking water was pretty bad, being stored in wooden barrels. Condensers on a ship were unheard of then.

Nevertheless the science of navigation was as perfect then as now. Perhaps even more so in a way. For the captains had to find their longitude by observation of the heavenly bodies with a sextant and make rather intricate calculations – all the data provided for them by that wonderful institution, the Greenwich Observatory.

Now they have simply to look at their ship’s chronometer, which tells them their longitude by the difference of time between the ship and Greenwich – They have to ascertain the local time, of course. They still have to find their latitude by observation.

As a matter of fact, even now in 1932 – it is impossible to get the exact longitude by observation. That is why there was a Disputed Territory on the Border between S.A. and Victoria.

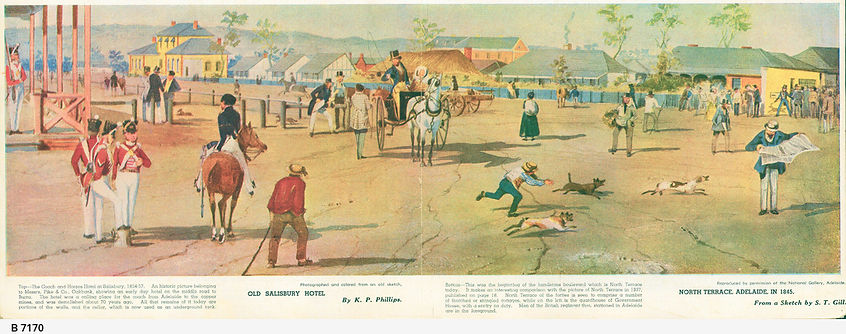

We arrived at Port Adelaide on the 26th November, 1854, in a torrid heat. There were no wharves for us to land at. There may have been some in existence, but I did not see any.

We were dumped out of the ship’s boat into the Port Adelaide mud. Port Adelaide was then named ‘Mudholia’ – Of course there was no railway. We went up to Adelaide per bullock dray. My father was no fool if he was a ‘new chum’, So he asked the bullock-driver his charge. This, father agreed to; but upon reaching the city, the man demanded more.

Father became angry, and was going to give the bullock-puncher a punching, which he was well able to do, as he was a high-class boxer, and strong and active; but mother, who was of a gentle nature, begged him, to pay the man and get away. What he paid, I don’t know, but that was the end of it.

Government immigrants were then brought out free, or were assisted. But my father and his family were not even assisted, as there were too many members – eight in all; so he himself paid the whole of our passage-money, amounting in all, I believe, to One hundred and Fifty Pounds

Now, in 1932, the Government hand out Five Pounds for every child brought into this over-populated world, instead of fining the parents Five Pounds each. And when the parents get old, and have squandered all their money, they are given a handsome annuity for the remainder of their lives! And the man who has been saving and practiced self-denial is super-taxed to pay it!!! Good business eh!

‘For ways that are dark, and tricks that are vain,’ Bret Harte once said that ‘the Heathen Chinee was peculiar’. But his way, if dark and vain, were not so silly and peculiar as are the ways of the Trades and Labor Unionists of Australia, who brought in and passed the above legislation.

Adelaide and South Australia itself were a great disillusionment to us all. The town was filthy. The climate was horrible after that of beautiful England. The dust and heat were terrible – to us then! [once acclimatised, we did not mind either.!] There was only the slimy Torrens water to drink. Many people were sunstruck – being too fullblooded to stand the heat really! Everybody had ophthalmia, both eyes sealed up with matter by morning, necessitating an application of hot water before they could be opened.

A fly of some kind gave everyone bunged eyes – so bunged, in fact, that an eye was invariable closed and black.

People’s lips were peeled by the sun, and the owners of the said lips had to protect them by keeping a gum leaf between them, Puggarees were worn down the back of the neck to ward off sunstroke.

Great whirlwinds came along every summer, and no one knew when the roof of his house would be lifted off, I myself saw the roof of Phillip Levi’s red-brick wholesale store, on the site where the Imperial Hotel now stands, at the corner of Grenfell and King William Streets, taken up into the air by a monster whirlwind and hurled into the centre of the latter thoroughfare,

I have seen a whirlwind at the rear of the Napoleon Bonaparte Hotel, King Wm. Street, twirl bottles about like feathers and smash them against a brick wall. Long, spiral whirl-winds were often seen a thousand feet high, and newspapers were carried up like thistledown.

These whirlwinds have ceased since cultivation of the soil has taken away the intense surface heat of the ground.

Still, Australia had its advantages. Grapes and other fruit were plentiful and delicious, and there were no diseases to attack the fruits then. There were no English sparrows, or starling, or rabbits.

– I quote the following death notices in 1920: –

-

Maryon-Wilson. – On the 24th July, at Great Caulfield Rectory, Essex, England, Albinia Frances, widow of Rev. George Maryon-Wilson, and third daughter of the late Bishop Short, Adelaide.’

-

Maryon-Wilson. – On the 24th July, at Greta Canfield Rectory, Dunmow, Essex, Albinia Frances, widow of the late Rev. George Maryon-Wilson, and third daughter of the late Augustus Short, first Bishop of Adelaide, in her 75th year.’

-

This was Miss Albinia Short who came out with us in the Albemarle. She was then nine years of age, or three years older than myself.

-

Her eldest sister was afterwards Mrs G. Glen, she having married a squatter in the South-East.

-

Her next sister was named Isabella, whom we always called Miss Short. She died in 1923. She was rather short in stature, and very pretty – Why she never married was a mystery to me. She was very slim in build.

-

-

Albinia and I, being girl and boy together, were chummy. There were two brothers – Henry and ‘Gertie’.

Next page: H H Tilbrook's Education

Reference: Transcript of PRG 180/1/6-7 Memoranda

-

Memoranda or Notes of Incidents by Henry Hammond Tilbrook

Read more: Clare Museum | H H Tilbrook

Pages in this series: