VOYAGE FROM GREYMOUTH, NEW ZEALAND, TO MELBOURNE In 1868

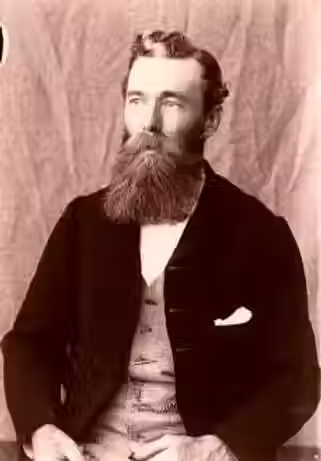

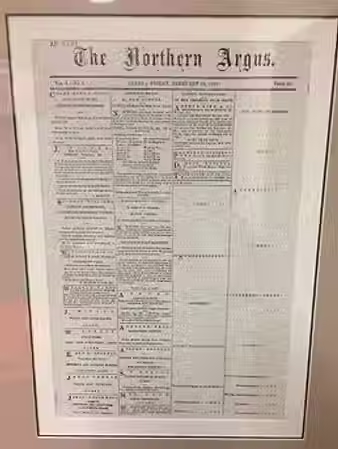

Henry Hammond Tilbrook became the founding editor of the Northern Argus in 1869, the newspaper of the Clare Valley, which was published until 2020.

-

When Tilbrook was about six years old, in 1854 the family sailed to South Australia on the Albermarle.

-

He worked for a short time as a typesetter at the Register in Adelaide (1861-3)

-

as well as working as a lamb minder for a short time, for Sir Thomas Elder (1864).

-

Tramped all over the same area (1865). Grocery delivery in Glenelg.

-

-

Worked at Ooraparinna Cattle and Sheep Run, far north of Wilpena (1865).

-

Enticed by the gold rush at the time, Tilbrook moved to New Zealand in February 1866 to try to make a living prospecting.

-

After having no luck with gold (in the rain), he moved on to work (1866-1868) for the Grey River Argus in Greymouth (first published 1865).

After a sojourn of two and a half years in New Zealand, I bid farewell to its magnificent mountains and forests, its rivers, and its – in a double sense – watery shores on – Tuesday, June 23rd, 1868.

It will thus be seen that it was winter, and I was getting away from the chilblains early. The S.S. Alhambra lay in the offing – or rather, out in the ocean.

I boarded the tugboat Dispatch, which was to take me a mile down the Grey River, across the treacherous and ever-moving bar, and through the curling waves to the side of the ocean boat, as she lay tossing in the stormy billows.

Concerning this same tugboat Dispatch, She was imported by Greymouth residents whilst I was there. She was the most powerful boat of this kind then on the West Coast, and the loyal citizens of Greymouth were proud that they had the pull of Hokitika, whose tug – the Lioness had hitherto beaten us.

It was the Lioness (illustrated below, right) that carried me from the S.S. South Australian across the Hokitika bar and up the Hokitika River to the town of that name, two and a half years previously.

I am now referring to our boat because of a little incident that occurred in the Grey River Argus office with regard to the spelling of the name.

The first time the name came into the office to be put into public print, the question arose, ‘How should it be spelt? – with an 'e' or an 'i'? Nobody seemed to know.

Finally the proprietors referred the matter to me. I having been in the Register office in Adelaide, naturally favored the spelling adopted there for that word – viz., with an 'e'. But I am against that method of spelling now that I am up in years, and favour the 'i'.

However that may be, Mr. Jack Arnot, one of the props, said very loyally, ‘We will adopt the spelling recommended by Harry.’ ‘Well,’ I said, ‘the leading daily newspaper of Adelaide always spelt the name with an e – thus, ‘Despatch.’ And Jack said, finally, ‘Very well, we will spell the name Despatch.’

So, ever afterwards, the boat was the Despatch. The Despatch took us across the bar from fresh water to salt, giving us all a good shaking as a farewell reminder of ‘The Coast’. She placed us alongside the Alhambra, aboard which we jumped from the vantage platform of the Despatch’s paddle-box.

There was a large number of passengers on the ocean boat; but the Alhambra was not crowded as was the South Australian, which boat, poor thing! was now lying at the bottom of the sea.

Once more Across the Tasman Sea.

Above: SS Alhambra, 642 tons. Built 1855 for P&O Company. Sold to McMeckan, Blackwood and Co, and for many years traded between Melbourne and New Zealand. Sold and converted into a collier and foundered off Port Stephens in July 1888.

Two and a half years had passed, and I had done well. I was going back to my sweetheart, dear Marianne, who had been true to me all that time, although others had attempted to win her, especially those of the squatter class, whom her brother Tom knew. Tom afterwards became Inspector Clode, of the mounted police.

My health by this time was not so robust as it had been after my two years of open-air life in Australia. Consequently my sea sickness was more prolonged.

The passengers were not so lively, either. Many unsuccessful people were voyaging back to Australia. Some were surly, some pleasant.

Many young women who had been at service in Hokitika and Greymouth were returning. Flirtations were attempted with these girls by the other sex all the way over.

I was sick for three days and three nights! When I say sick, I mean I was heaving up bile, at intervals, all the time. There was nothing else in my innermost recesses except bile. So that was all that I could feed the fishes on.

During that period, night and day, I was on deck, near the grateful warmth of the great funnel. Sitting there very helpless, I saw all that was going on. Two girls of about twenty-five thought they had made inroads into the hearts of two returning diggers – of doubtful morals! But the girls were mistaken. They had not.

I heard all that the girls said to each other concerning the men, after the men had gone below. – how one believed that he was very fond of her; and how the second girl was sure the second man was sweet on her. These girls were not flappers – dear, delightful flappers who jump to conclusions about men being in love with them without the slightest grounds but just in accordance with their own wishes.

They were not flappers, I say, but demure, staid young women who must have had considerable knowledge, if not experience, of the vicious ways of many fast men. And so they deceived themselves as easily as do young flappers.

The men gave themselves away before me, in the girls’ absence as freely as all such men always do. They were just free-lances, and matrimony was far from their thoughts. I, the silent onlooker, quietly watched the game of the spiders and the flies.

The ‘flies’ did not fall into the web, I am pleased to say, after all. Some sense of caution took possession of the girls, and they were saved. Yet the men were not of the vicious class, but just ordinary people without a home whom we find everywhere knocking about the world.

One of those kind of adventurers whom I met in Adelaide long after this, when I had a happy home of my own with my beloved Marianne, said to me: – I have knocked about all over the world, but I have got no home! I am awfully miserable. My brother has settled down, and he has a comfortable little wife and a happy home. But I have neither!’ And that is the sad fate of many others.

The voyage was dull. The weather was dull. The clouds were heavy and dark. But we encountered no heavy storms as on the other voyage. Everything was mediocre.

I was older, too – about twenty years now. That made the outlook different. The clouds loomed up like mountain ranges in the distance – heavy stratus and cirro-stratus showed around. No interesting cumulus as in the summer time.

No very high waves – all at one dull, uninteresting level. The distant view was murky. I was very ill! Was that why? I also had to ponder out my prospects ahead. Although my brother George had declined to join me in starting a newspaper at the Burra in South Australia, I had not given up the idea.

Sitting there on the deck of the steamer, near the big funnel, grateful for its warmth, I pondered over these and other things. My real intention was to return to Adelaide, stay a week or two there, and go off to the Gympie goldfields in Queensland, from whence highly-colored reports were being received.

One day, whilst in Greymouth, two diggers were walking in front of me. Said one to the other, referring to a Gympie report, ‘Good God! A solid mountain of gold!!!’ They were off there, of course! – to get their share of the golden mountain!

Steamship companies of those days were generally credited with rolling along these wondrous stories. I sat on the deck of the Alhambra three days and three nights without a bite of food going between my lips. What my condition was at the end of that time – I every now and again trying to heave my very in’ards over the side of the ship – may be faintly guessed.

I saw the stokers come up from the inferno below, stripped to the waist, to get some of the cold air on their heated bodies and into their lungs. At the end of the third day out, in the Tasman Sea, I was sitting, looking down the hatchway, eying some tempting apples displayed there.

A humane digger had often looked me over. On this occasion he came up and said, ‘You look awfully ill! Can I do anything for you? Shall I fetch you some brandy?’ I replied, No, – I could not touch spirits, but he might get me a pound of those apples down there. I handed him some money. He brought me the tempting-looking fruit.

I tried to bite an apple, but got an electric shock! My teeth were loose, several were on edge, and a nasty jar ensued when they met. However, by careful manipulation I got through one of the apples, and soon began to feel better. By the time the pound avoirdupois was disposed of I was another man. Then my appetite returned, and I was alright.

We steamed on for several days. At last, one day I saw land far away ahead. I observed to a surly-looking fellow who was a passenger, ‘Do you see those trees on the ranges over there?’ ‘Trees!’ he sneered. ‘You must have dirt in your eyes!’ – only the word he used was not what I have put down. I said no more to the human brute. In a short time, however, the trees were visible to everyone on board. That land was Gippsland.

We passed through Bass Strait on Sunday, June 28th, 1868, and saw Kent Group and several other islands. What a grand sight is land after a sea voyage! – or during a sea voyage! Islands look beautiful in the extreme!

The Sandridge Lagoon and the wharf outside Harpers Oatmeal and Starch Factory complex, 1900

On Monday morning, June 29th, 1868, in the small hours, the vessel passed through the Heads, traversed Port Phillip and Hobson’s Bay, and reached Sandridge – (now Port Melbourne) – before daybreak on Monday, June 29th, 1868.

Lodging-house touts and cabmen were there even at that early hour. Asked a cabby his fare to drive four of us to Melbourne. He replied Five shillings each! We were not having any just then! but stayed on the ship till daylight. Then took train for about sixpence each to Flinders street Station.

One of our party knew of a nice lodging-house in Lonsdale Street. Taking a cab from Flinders Street, we arrived there in time for breakfast, and were made very comfortable.

She was of good figure, and handsome, and yet obliging and courteous – a strange combination, and hitherto unknown among modern girls!

Above: Typical Lonsdale St. lodgings

That night I slept in a bed of down! But the motions of the ship seemed to heave the bed and floor up in sinuous waves. I experienced he same sensation while walking along Bourke Street in the daytime. The pavement kept rising and falling.

Melbourne I found much improved since my previous passage through it. Great buildings had gone up everywhere. Bourke Street on the hill near King Street, near the site of my old lodgings, had already been transformed. Old brick building had given place to new and handsome structures.

The prevailing tone was, however, black, or nearly so, making the place look sombre – in contra-distinction to the brightness of Adelaide. This was the result of using basalt as the chief building-stone.

As before, I explored the ‘Queen City of the South’ and enjoyed strolls in the various parks and gardens. I also once more visited the Botanic Garden on the south bank of the Yarra River. I made up my mind to take the very first steamer for Adelaide to avoid further sea-sickness.

But I did not escape, as the sequel will show. I had already, while in New Zealand, obtained a bank draft for the sum of Forty Pounds, payable at the Bank of South Australia in Adelaide. I learned afterwards that I was travelling ahead of my draft!

Upon telling the maid and her mistress that I was departing for Adelaide at once, the girl expressed her sorrow that I was going so soon. Whilst the mistress was exceedingly moderate in her charges.

VOYAGE – MELBOURNE TO ADELAIDE

June - July 1868

S.S.Coorong Twin Screws

S.S. COORONG - built by J G Lawrie & Company Whiteinch, Yard No 17

Propulsion: Steam 2cyl 70nhp screw

Built: 1862

Ship Type: Iron Steamship

On Tuesday, June 30th, 1868, I left Melbourne, on board the twin-screw S.S. Coorong. She was a small boat. The only available berth was in the bows, right up at the extreme point of the Forecastle! Had I had more experience, I would have refused it. It is absolutely the worst position in a ship.

Another week in Melbourne would not have rendered me more liable to seasickness. After the voyage across the Tasman Sea from New Zealand I thought I was immune for a time. Therein I was wrong!

Getting through Hobson’s Bay and Port Phillip, and out through the Heads, into the ocean we found it exceedingly rough. I, in ‘Newcastle Point’, was tossed up and down, high into the air, and down into the depths I was being properly rocked in the cradle of the deep!

This continued mercilessly and without cessation, and I soon became as sick as I had ever been. But I must have been ‘case-hardened’ to a certain extent, for after twelve hours of violent sickness, I suddenly recovered. Father Neptune had done his worst! I was mal-de-mer proof after that.

All his desperate tossings and twistings affected me no more. I was as tough and immune as the hardiest mariner. Going along the Victorian coast, we called at Port Fairy near Warrnambool, on Wednesday July 1st, 1868. We left the same day, and passed close to Lady Julia Percy Island and Lawrence Rock.

Thirty-seven years afterwards, whilst upon one of my land trips with friend Lester over the S.E. country of South Australia and the Western District Victoria we got to Portland Heads (Vic.). I was taking photographs there. I asked a solitary Italian whom I encountered the name of a prominent flat-topped island out to sea. He told me that it was Lawrence Rock! A rather strange coincidence!

I had thus seen the rock from both land and sea. Lady Julia Percy Island was also a rock, with lofty, precipitous cliffs for sides. It looked very picturesque.

Both these islands were once part of the main land. Further along the coast I admired the scenery and the seascapes and the cloudscapes. Having that bent is why, I suppose, I took up photography when the leisure and the opportunity came my way.

On Thursday, July 2nd, 1868, getting out of sight of land I leaned over the engine skylights and watched the triple eccentric shafts rising and falling. I noticed the immense iron nuts on top of the three piston-rods above the steam cylinders. They were spick and span, and shone with a newly-cleaned brilliancy. I watched this interesting machinery awhile.

Then I went away a few yards and sat down upon a seat. The morning was calm, with no one on deck. Suddenly, I felt the shock of a great explosion! The ship trembled.

Had there been any U-boats about then, I should have thought it was a torpedo. Looking towards the engine-room, I saw the skylights I had been looking down, flying upwards and splintered glass crashing about. Then followed a rush of steam.

I, instanter, went forward to see what was the matter. The Cook shot up from a narrow passage-way, through the obscuring steam, and bolted away from the danger zone. How he did run! The Captain, Mate, and others, darting out of the cabin, made towards the scene of the explosion.

With the steam clearing away, we saw that the top of one of the steam cylinders which I had been admiring a few minutes before had blown to smithereens, disabling one of the twin screws. Fortunately no one was injured.

After a time, one propeller was set in motion, and we commenced to drag a slow and weary way towards Adelaide. The dead screw acted as a drag-anchor, and retarded our progress. Keeping on thus for some days and nights till Cape Jervois was sighted, a tug was telegraphed for. The tugboat Yatala was sent down the coast from Adelaide to meet us.

On July 3rd, we sighted Cape Willoughby, passed The Pages, Cape St Albans, Antechamber Bay, Cape Coudes, Christmas Cove, and Cape Jervois. Then passed through Backstairs Passage. After going by Rapid Bay, the Yatala hove in sight. She threw us a towrope.

We went along then in grand style, with steam up on both vessels, and arrived at Port Adelaide on Saturday, July 4th, 1868.

We thus took five days to complete a voyage which is now done by the modern steamers in thirty-eight hours.

Iron paddle tug boat YATALA of 210 Tonnes, underway, built in 1877, owned by Adelaide Steam Ship Co Ltd.

In 1911, the steamtug Yatala was still at work at Port Adelaide. She was very swift, and, while towing us, took us past other boats in fine style, up the Port river and to one of the wharves.

On this voyage, I became acquainted with a young man who was a South Australian farmer’s son. He had been to Victoria to work on a farm there. He recounted all his adventures in that colony. Circumstances compelled him to leave, and he was returning home.

After we had landed, I was his guide all over the city. He told me he was very pleased to meet a young fellow like myself who would show him around the metropolis without going into public houses for a drink. This latter I never did, on principle. Bad habits are created too easily. And they stick to one!

With regard to the bank draft for £40, I took it to the Bank of South Australia on North Terrace – (where the South Australian Club Hotel stands now) – to have it cashed. The bank teller said they had no advices regarding it, and refused payment until advices arrived.

However, he eventually said that if I could get anyone to identify me, he would cash it. Looking over the counter, I said: ‘There’s a man over there – Harry Sparks – who knows me and can identify me.’

My brother George had been courting Harry Sparks’ eldest sister. They lived in a two-storied house in Kermode Street. Harry was a clerk in the bank, and I had spotted him immediately I entered the doors.

The teller look across at Harry Sparks, then handed me over forty sovereigns without another word.

Harry Sparks was afterwards Manager of the South Australian Company which owned so much land in Adelaide.

Some years after this, when I had established The Northern Argus newspaper and printing office in Clare, Harry Sparks bought over for the South Australian Company land that I had lent Five Hundred Pounds – (£500) – on on mortgage.

And upon the mortgage maturing, they paid me the money back, with all interest owing.

That land is where Messrs. D. & J. Fowler’s wholesale warehouse now stands, on the corner of North Terrace and Morphett Street, near the Overway Railway Bridge.

Below: Bridge spanning the railway line, a little west of Morphett Street, 1867

ARRIVAL IN ADELAIDE. 1868.

Owing to my hurried departure from Melbourne, I had anticipated my letter to my beloved Marianne by arriving first. I knocked at the door in Tynte Street, North Adelaide. It was opened by a vision of the most beauteous womanhood I had ever seen!

It was Marianne – my own beloved. She flew to my arms – her arms around my neck, mine around her shapely waist. I was nearly mad with happiness. I at once gave up all idea of going to the Gympie Goldfields. I had had enough of partings.

She clung to me in an ecstacy of delight. She took me inside and fed me with some of her exquisite cookery. In her letters to me, she had told me that she did her hair in ringlets. I wrote her that I thought curls were fit only for little girls. But how handsome she looked in them!

She was a fine girl, too, as well as handsome. Our love became a stark staring madness. She could not exist while I was out of her sight, and I was just as wretched when absent from her.

I now resolved to see if her brother Alfred Clode would become my partner in the newspaper venture I purposed launching at the Burra.

I learned that he would be only too pleased to join me. We did eventually start The Northern Argus, but in Clare. Upon going to the Burra to spy out the land, I found that the mining boom had collapsed, the great copper mine having ceased work.

Being advised by Mr. Charles Dawson that Clare was a better spot, I walked across country there one day and night from Mount Bryan Flat, and came to the conclusion that that town would suit me. And that was how The Northern Argus originated.

In the meantime, my intended partner being then at Mount Gambier, I thought I would try my luck at the Echunga diggings, which were then in full swing. I accordingly tramped twenty-five miles, starting from North Adelaide, with my swag on my back, up the hills to Jupiter Creek, and prospected there while waiting for him.

My mate not appearing, I saw it was useless staying there. The weather became wet and stormy. It appears that this affected my glorious sweetheart to such an extent that she was crying herself to sleep about me every night.

I was right enough in my calico tent at Jupiter Creek, and it was nothing to what I had put up with in New Zealand. But she did not know this.

One afternoon I got a piteous letter from her, saying that if I did not come back to her that very day the anxiety would make her ill. It was four o’clock in the afternoon. Everything was wet – tent, blanket, clothing and all.

Nevertheless I packed up everything at once, shouldered my heavy swag, weighing once again quite one hundred pounds, and started on my all-night tramp of twenty-five miles to Adelaide. The latter half of it was downhill at anyrate. But, oh, my swag was heavy! It bore me down.

I shall never forget it. My feet were tired. I was knocked up while bearing the swag, but light of foot without it. I kept on my way, over the ranges in the dark, till I had passed through Glen Osmond, and finally reached the Racecourse Hotel, on the border of the South Park Lands at Parkside or Eastwood.

Knocking up the publican thus early in the morning, for it was still dark, I asked him to take charge of my burden till the following day. He was one of the human sort, and, not a bit cross about being roused out of his bed, he accepted it with great goodwill. What a relief!

I felt as if I had wings! The rest of the journey across those Park Lands, through the city, and across the other Park Lands to Tynte Street, North Adelaide, was a mere nothing! By this time it was daylight, and my glorious Marianne, en deshabille opened the door to me. And she cried in my arms.

While at Jupiter Creek, I prospected considerably, but gold was very scarce. Only in the upper part of the gully was good, coarse, gold obtained. Another man and I sank holes on the banks of the Onkaparinga, but got only just a trace. One shaft that we sank was twelve feet deep. We had no windlass, but adopted the platform method as in New Zealand. Nevertheless the place was not half prospected.

Few of the holes were sunk to bottom – that is, to wash-dirt. Payable gold ought to be found there yet.

I stayed with Marianne in North Adelaide until her brother came from Mount Gambier. Barossa, beyond Gawler, was having its rush then. We decided to try our luck there. Taking the train to Gawler, we tramped eastward to the diggings. Nice-looking iron conglomerate was plentiful, and the country looked very promising for gold.

The rich claims were all at the head of one long gully. There the gold was nuggetty, not having travelled far from the reefs. The only place left was down the gully, where the gold was fine. It had been washed down a long way from the matrix, and was consequently ground small.

We sank a few holes without success, then purchased a claim that was half worked out. It had a shaft thirty feet deep, equipped with windlass, rope, and buckets; besides which there were a cradle and a puddling tub – for the wash-dirt was clay (pipeclay), and had to be puddled before being put through the cradle.

After that came the ‘panning out’ in a shallow prospecting dish. That was my special job, as I had learnt the art of ‘panning out’ on the New Zealand goldfields.

After puddling out the clay and cradling out the mullock, it was pleasant to wash out the residue, and watch the grains of gold glittering around the edge of the dish.

We had hard work driving tunnels. The wash-dirt was many feet thick, and might have paid to ‘paddock’ had there been plenty of water for hydraulic sluicing.

At Kumera, on the Teremakau River, N.Z., not far from Greymouth, where [at Kumera] ‘King’ Seddon lived before he became Premier by the Labor vote, hydraulic mining was carried on on a very large scale. But water was so abundant there, that any quantity of it at high pressure could be brought to bear upon any part of the field.

At dry Barossa things were very different. There we had to pick and shovel each bucket of ‘dirt’, haul it to the surface, puddle it, cradle it, and pan out the residue. And we obtained the magnificent reward of one grain of gold from every bucket of dirt that we mined! That was the average.

Our biggest nugget weighed one grain. I have it yet in a little bottle in my cashbox, along with my half of the gold that we obtained there – and a little gold from other parts – for did not sell so much as a shilling’s worth.

Our tent was pitched on the bank of a picturesque creek. At the back of the tent, within a yard, was a big hole in the earth. I belonged to an iguana three or four feet long. He came out foraging every night.

On Saturdays my mate and I took it in turns, – that is, alternately – to go to Adelaide, coming back on Sunday night or Monday morning. Thus I had then a fortnight’s separation from my beloved Marianne; and it was with the intensest longings that we looked forward to those meetings.

Short-lived as they were, they were full of happiness for us. But the partings were hateful. Things were doubtful with me, too – for I still had to make my way through life and provide a home for her.

View of the diggings at Barossa_1868

By this time I had news of the newspaper printing plant, which I had ordered from Melbourne, being on the way, and we left the Barossa diggings to make a start in Clare.

As I have mentioned, upon my arrival from New Zealand I went to the Burra to investigate, as I intended starting the newspaper there.

But the mine had ceased working, and things were very dull. Going further on, to Mr. Charley Dawson’s hotel on Mount Bryan Flat, twelve miles out, I was made very welcome.

But I had a queer experience upon entering the hotel parlor. Charley was telling a Bush yarn to the customers there. It was about the discovery of a whitened floursack in a cave during the Blackfellows’ raids upon the huts on the Ooraparinna Run in 1865. He told the story as though he were the finder.

Whereas he had nothing whatever to do with it. It was I who had made the discovery, crawled into the cave, and brought out the sack, taking it thence on my horse to the head station, and handing it over to Charley.

Charley, good old boy, even then had a short-circuited memory – a troublesome lapsus memoriae – and he lived to a ripe age of over ninety. He had complained to me, after that, of his failing memory.

Here is another instance:

We were talking together about Inspector Tom Clode (pictured seated above, second from left) , just then deceased. Charley and I had paid the funeral expenses of Tom’s father, who died in the Adelaide Hospital.

Charley claimed to me that he himself had paid the whole amount. Upon my correcting him, pointing out that he had written me asking me to pay half, which I did, he looked up at me in astonishment, but went on with his story.

No doubt Charley had told the tale of the Cave and the Floursack so often, that at last he really believed himself to be the principal. I have known other similar cases of mental aberration.

I once told a friend of how I saved myself from sea-sickness by inhaling the strong fume of onions during a hurricane in the Tasman Sea. After this he himself went for a trip up Spencer’s Gulf. When he came back he told me an imaginary yarn to the same effect.

He had grabbed some onions from the deck and had saved himself from being sick! I never told him any more of my experiences.

To return to my subject. Charley told me that the best place to start my paper was Clare. So next day, at 8 a.m., I started off, and walked the forty miles, getting into Main Street, Clare, at two o’clock the following morning.

I then decided upon Clare as the scene of my business venture.

Arriving at two in the morning, I camped on the creek that runs through what is now the Clare Oval, and started for Adelaide per coach to Kapunda at 6 a.m.

But no office or shop was procurable in Main Street.

So eventually we enlisted the services of Mr. Durrant, a builder, to build us an iron Office in Lennon Street. We stayed in this for two and a half years.

Then I got Mr. Chas Kimber, the miller, to build us an office in Main Street, at a rental of One Pound per week. The Northern Argus has been domiciled there ever since, although it has long since been too small for the business.

One thing people don’t know. Owing to the delay in getting a building, we had to cart the Northern Argus plant over the ranges to Mr. Joseph Brinkworth’s farm on Blyth Plains, and keep it there till the office was ready.

Then, the Northern Argus was issued as a weekly. Afterwards I brought it out as a bi-weekly for several years.

At the time of this writing, my son, Reginald Henry Tilbrook, is issuing it as a six-page weekly.

I had better state here, to dissipate all doubts, that I, Henry Hammond Tilbrook, paid for the whole of the Northern Argus plant with my own money.

My partner, Mr . Alfred Clode, put no money into the plant, but bought one bale of paper, which (cost) Twenty Pounds sterling – (£20).

Afterwards, less than two years from that time, when Mr. Alfred Clode went out of the partnership, I paid him nearly ten times the sum that he expended upon that bale of paper. He thus did very well out of £20 capital, as he received the same wages while working as I myself.

When I let my brother Alfred into the partnership, he paid Ninety Pounds sterling – (£90). to come in.

But I took none of that money for my own use, but placed it in the office current banking account.

Yet I allowed my partners to take equal shares in all the profits, and to receive the same weekly wage as myself.

It will thus be seen that I treated my partners very fairly. It was hard work getting the venture on a sound footing. At first I ‘set up’ the whole of the paper myself – six pp. folio demy.

I arose at four o’clock each morning and worked hard till ten o’clock at night. Then we worked off the issue on Thursday nights.

Extracted from: 1_1-2_Tilbrook_Reminiscences

Others: 1_3-5_Tilbrook_CampingOutExpeditions

In order to see my beloved Marianne, I, one Thursday night, after printing and publishing the Argus, started at midnight, on foot,

-

walked eight miles to Blyth Plains,

-

hunted in the dark over Mr. J. Brinkworth’s four-hundred acre farm for my horse,

-

caught him, saddled and bridled him,

-

rode to Tarlee – about forty-one miles –

-

paddocked my horse at Sinclair’s farm there,

-

walked another eleven miles to Kapunda,

-

– with spurs clinking at my heels – for I had carried my silver-mounted (spurs) to New Zealand and back

-

– and carrying an eleven-pound plumcake (a present from Mrs. J. B. to her mother, Mrs Clode) and then

-

trained it fifty miles to Adelaide.

Also see: Art Gallery SA Photos by H H Tilbrook

Then happiness till Monday morning with my beloved. After that the awful parting, for I would not see her again for several months.

The Northern Argus was first published in February, 1869.

(First edition illustrated right)

We were married on the first of January, 1870, in Christ Church, North Adelaide, by Archdeacon Marryat, who presented Marianne with a valuable book, entitled ‘The Land and the Book’ (a guide to the Holy Land based upon biblical references)

Then our happiness was complete. But after thirty-seven and a half years of happiness my beloved slipped from my grasp across the Great River, and was lost in the mists beyond, leaving me alone.

And now let the curtain fall.

Henry (Harry to his friends) later went on a number of photographic excursions with Fred Lester and others, but usually left them and went off alone, or solus as he called it, carrying his heavy camera gear in search of suitable subjects.

Photographic excursions he mentions in his writings and included at the S.A. Gallery are:

1894 - The Flinders Ranges

1898 - To Mount Gambier and district

1899 - To the top of Mount Bryan, north of Burra.

1900 - Back to the South East

1905 - Mount Gambier and Portland, Victoria.